Videos by American Songwriter

Born in 1896 of Russian-Jewish immigrant parents and raised in poverty on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, lyricist E.Y. (Yip) Harburg never forgot his roots when he versified. His parents worked in a ladies’ garment sweatshop, where Yip also worked, packing clothes. The youngest of four children, Yip fought in street gangs against Italians and Irish. But, according to Harburg, “We didn’t know we were poor, we were too busy living life to the fullest.“ Today, he is still mostly remembered for penning the words to blockbuster musicals such as The Wizard of Oz, Finian’s Rainbow and Cabin in the Sky. But, few appreciate his deeper dreams of democratic socialism behind so many of his lyrics and poems.

Yip and his peers were exposed to a wide range of educational and cultural influences that gave them a unique preparation for their later profession. Though his parents were Orthodox Jews, Harburg characterized them more as “tongue-in-cheek” Orthodox. After the loss of his elder brother to cancer and then his mother, he became agnostic. “The House of God never had much appeal for me”, he stated. “Anyhow, I found a substitute temple—the theater.” The young Harburg scraped together his dimes and quarters to watch performers such as Al Jolson, Fanny Brice, Ed Wynn and Bert Lahr (who later rose to fame by singing Harburg’s lyrics to “If I Were King of the Forest” in The Wizard of Oz.)

As a boy and young man, Yip frequented the Yiddish theater, vaudeville houses and eventually the Broadway stage and also acted in his school

plays where all the popular songs of the day were sung. He also began writing in school. At the time, many New schools offered a rigorous training in the classic poetic form, especially Townsend Harris High School, where Yip attended with Ira Gerswhin. Columnist Franklin P. Adams, who then wrote for The Herald Tribune, offered writers with clever observations of current affairs an opportunity to see their work in print and Harburg’s light classical verse soon appeared

frequently. “We were well versed in all French forms: the ballad, the triolet, the rondeau, the villanelle, the sonnet”, Yip said at a UCLA talk in 1977. “We were highly disciplined.”

After attending City College, Harburg chose to work in a Uruguay factory in 1917, which provided him an opportunity to make a decent wage, while avoiding being drafted against his beliefs into the First World War. Following the war, he married, fathered two children and became the co-owner of an electrical appliance company, that did well, but after seven years went bankrupt during the 1929 economic crash. After his business failure, Yip gravitated to songwriting. “I left the fantasy of business for the harsh reality of musical theatre”, he later joked.

Shortly thereafter, he literally turned his fate on a dime and wrote “Brother, Can you Spare a Dime,” with composer Jay Gorney. Now widely considered the anthem of the Depression, it remains a masterfully poetic sing that speaks to anyone who has chased the American dream, failed, and now seeks both economic and spiritual uplifting. Some historians have speculated that the song actually helped to push forward Franklin D. Roosevelt’s progressive social agenda. Here, with a haunting melody, he masterfully made personal a radical perspective of the country’s economic downfall with lyrics such as:

They used to tell me

I was building a dream

with peace and glory ahead.

Why should I be standing in line

just waiting for bread?

Because of its poignant reflection of workers during the Depression who had been forgotten or misplaced, this song became a milestone for Harburg and propelled his career to unimagined heights. “I didn’t want to write a song that depressed people,” he told Morley Safer in a 1978 60 Minutes interview. “I wanted to write a song that made people think.”

Hooray for What?, conceived and produced by Harburg in 1937, essentially an anti-war musical comedy, appeared during the threat of rising fascism and militarism in Europe and Japan. The title song defiantly asks: “Hooray for what? Throw out your chest, throw up your hat, another strike—another war, Can come to that.”

Cabin in the Sky, with a score by Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg, was the first all-black musical to be adapted to a film that headlined black talent such as Duke Ellington and Lena Horne, and that was intended for a wider general audience in 1943. Harburg saw Arlen as the perfect composer for this musical because of his ability to synthesize African-American rhythms with Jewish liturgical melodies.

According to Harold Myerson and Ernie Harburg in their book,

Who Put the Rainbow in the Wizard of Oz?: Yip Harburg, Lyricist, Yip Harburg called the 1944 musical Bloomer Girl that he wrote with composer Harold Arlen and librettists Fred Saidy and Sig Herzig, a show about the “indivisibility of human freedom.” Co-directed by Harburg, it was based on the pre-Civil War political activities of Amelia Bloomer, who fought against slavery and for women‘s suffrage by encouraging women to drop their hoopskirts and wear pants or “bloomers“ like men.

Set on the eve of the Civil War, the play boldly addresses both the poignant issues of women’s emancipation and racial inequality. The play’s heroine is a suffragette whose home is a way station for the Underground Railroad and it ends with the powerful song, “The Eagle and Me” sung by a runaway slave. Many have seen the song with lyrics like “…free as the sun is free, that’s how it’s gotta be…we gotta be free, the eagle and me,” as the first theatre song of the civil rights movement.

“There were so many new issues coming up with Roosevelt in those years,” Yip said, according to Dan Barker in his essay “The Theater was his Temple: Yip Harburg: Secular Songwriter”. “and we were trying to deal with the inherent fear of change—to show that whenever a new idea or a new change in society arises, there’ll be a majority that will fight you, that will call you a dirty radical or a red.”

But, despite Harburg’s strident, seemingly controversial liberal views, he remained a magnet for great talent. With music composed by Burton Lane, his most famous show, Finian’s Rainbow, was considered groundbreaking for its time because it directly scrutinized racism in America and was one of the first musicals to have a racially integrated cast and chorus. Here, we have a bi-racial Southern tenants union teaming up with an Irish leprechaun in pursuit of a pot of gold. It’s no wonder that, at the time, many found the play unsettling, as it spotlighted the evils of Jim Crow laws and the inherent unfairness behind capitalism. Cleverly embedded in this play is the song “When the Idle Poor Become the Idle Rich,” which shows how society perceives a person problems differently based on their economic and social status.

Addressing the question of how a production that was really a ‘socialist musical’ could be pulled off at a time when socialism was a scary word, Myerson and Harburg write, “While its racial liberalism was immediately obvious to any audience, its Marxism was apprehended at most on the level of parable only–the only level, that is, which would be acceptable to a mainstream audience, especially in 1947.”

The 1957 musical Jamaica, with a book by Harburg and Saidy and music by Harold Arlen, was originally conceived as Pigeon Island, a musical that spoke out against colonialism, commercial culture and the threat of nuclear war. Instead, producer, David Merrick, turned it on its head, resulting a much milder plotted vehicle for singer, Lena Horne. Harburg adamantly refused the attend its opening in protest against the libretto changes.

And, what’s in a name? Apparently Yip’s surname symbolizes his politics, literally. Though born Isadore Hochberg and called Edgar Harburg as a child, he became Yip, not as some believe because of the Yiddish name Yipsel, but for YPSI, an acronym for the Young People’s Socialist League. Harburg himself added: “ I was nicknamed Yips(e)l which is the Yiddish term for a squirrel and evidently I was quite a flighty kid. People around me were very frightened, so I tried to lift

them up all the time with games and fun and running.”

But, even though Harburg was not a Communist, he did have many friends whose ideologies were to the left. Not surprisingly, he was targeted by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and blacklisted from pictures, television and radio in 1950 for more than a decade, largely because he refused to name names of alleged Communist sympathizers for Senator Joe McCarthy‘s committee. Broadway was his salvation because they were less restrictive. When recruited with Harold Arlen in 1956 to work on the music for a movie about Nellie Bly, the pioneering female journalist nationally known for reporting on workplace conditions and government corruption and her daring undercover assignments, Harburg recalled going before the International Alliance for Theatrical Stage Employees head, to discuss removing his name from the blacklist. They apparently had a file on him “thicker than all my works” and wanted to know if the ‘Joe’ in his hit song “Happiness is a Thing Called Joe” referred to Joe Stalin.

They also suggested that he write an article for the American Legion’s magazine with a title something like “I Was a Dupe for the Communists.”

Nonetheless, he continued to work on Broadway, including the penning of words to the musical, “The Happiest Girl in the World” (based on

Lysistrata by Aristophanes), that had a strong anti-militarism and a pro-woman theme. When the blacklist ended, he and Harold Arlen wrote

the music for the animated movie “Gay Purr-ee”, which included a satiric song called “The Money Cat.”

Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, he published books of light satirical verses and performed narrated concerts at New York’s Ninety-second Street Y “Lyrics and Lyricists” series that he helped conceive and in which he was the first lyricist to perform. He also appeared on numerous television shows, including The Dick Cavett Show.

Harburg, who kept writing up until his death in 1981, believed that people should not be forced to live below their social, political or economic means. He advocated that all people should be guaranteed basic human rights, social and political equality, free education, economic opportunity and universal health care, long before these concepts became part of today’s fragmented social fabric. Indeed, he spent most of his adult life fighting causes under the often

adversarial backdrops of popular theatre and tinsel-town Hollywood. In the opinion of his son, Ernest, he was Broadway’s social commentator,

and one who could “gild the philosophic pill”, with witticism and a unique lyric style.

Harburg’s lyrics are largely about the everyday man and woman, the working poor the disenfranchised, the oppressed, the weary. No one could ever have accused him of losing his social consciousness nor his hardscrabble roots. Nonetheless, he remained full of youthful energy, whimsy and optimism. “The most important word in “Over the Rainbow” is dare,” Yip’s son, Ernie Harburg, told Theatre Review columnist David Hinckley. “The dreams you dare to dream. The courage to make the journey and find your home in the world.”

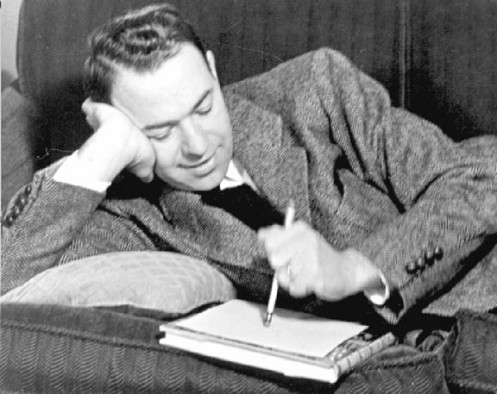

“I love Yip’s lyrics for their compassion, their understanding that life is not a bed of roses, but that there is always hope,” stated the late singer Lena Horne. Vocalist Tony Bennett described Yip as “…the greatest lyric writer of them all.” In a famous photograph of Yip Harburg, seated at his manual typewriter

in a contemplative mood, looking out the window of his Central Park West apartment, with pen in hand, on the windowsill is a well-used copy of “American Thesaurus of Slang”. This seems proof positive of Harburg’s devotion to speaking the language of the common person and of his conviction that ordinary people of the world do indeed have power.

Leigh Donaldson’s writing on international/national/ regional politics, business, social issues, history, art, culture and travel have appeared in print and online publications such as American Legacy Magazine, Progressive Media Project, World Report, The Public Press, Common Dreams.org News Center and elsewhere. He is the recipient of several awards including a National Press Foundation Award, a Fund for Investigative Journalism grant and a Goldstein Research Award. He is also a New York Times fellow with the International Longevity Center USA. His book “The Written Song: Antebellum African-American Press in the Northeast” will be published by McFarland & Co. Publishers next year.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.