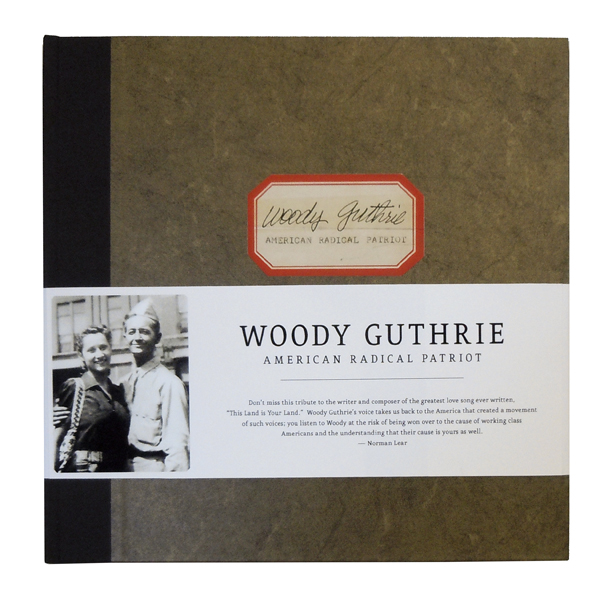

Woody Guthrie

American Radical Patriot

(Rounder)

Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars

Videos by American Songwriter

Woody Guthrie’s recording career began when he was 27 and lasted only 10 years, and yet, nearly 50 years after his death, he remains one of the most fascinating figures in American history. Surveys of his life and work still manage to produce fresh revelations, and American Radical Patriot, Rounder Records’ just-released collection of government-related Guthrie recordings, provides extraordinary new insight into the complex mind of this simple-sounding folk icon.

With six CDs, a documentary DVD and a 78-rpm disc — packaged as a photo album with a 60-page edition of the downloadable 258-page book by Rounder Records co-founder and box producer Bill Nowlin (included as a PDF on disc 1) — it is, as a friend noted, “a lot to digest.” But this combined chronicle of Alan Lomax’s Library of Congress interviews, 17 of the 26 songs Guthrie wrote in 30 days for the Bonneville Power Administration, and his war-effort, pro-union and anti-venereal disease contributions, resoundingly answers the text’s question, “Woody Guthrie: communist or ‘commonist’?”

Guthrie’s empathy for society’s downtrodden is well-documented, but in the Lomax interviews, he expresses the depth of his affinity. Describing his enjoyment of the company of “colored” people, he also addresses the racial biases that made his opinion almost dangerous.

He talks about the temporary nature of the oil booms, and the temporary nature of the corresponding housing, then draws a direct line from oil to poverty and the dustbowl migration to California — and the prejudice those dustbowl refugees encountered. Discussing his “Talkin’ Dustbowl Blues,” Guthrie explains its reach in a way that drives home the impact those events had.

“I wrote it just to talk about me, but later I found out it fits several hundred thousand,” he says.

Guthrie’s speech is filled with poetry, in cadences rappers would envy. When Lomax asks Guthrie to define the blues, the soliloquy he gets in return is truly Shakespearean.

Never released in their entirety in the United States until now, the Library of Congress sessions contain more than 100 minutes of “new” dialogue and several songs not included on the 1964 Elektra and 1988 Rounder editions. Even those who know his history through books or other sources will find these horse’s-mouth descriptions fascinating. Hearing Guthrie’s clear-as-a-bell voice deliver an unabridged detailing of his life and music — and the circumstances behind the events that informed his songwriting — gives each story, each verse, a new immediacy, though his laconic delivery casts a matter-of-fact tone to some heartbreaking events, such as the death of his revered sister and his mother’s subsequent institutionalization.

The kids were farmed out to other families; he mentions sharing a two-room shack with 10 other people. They had to cram in bed head-to-toe.

“We had everybody’s feet in everybody’s faces; you know how that is,” he tells Lomax, who likely couldn’t possibly know how it really was, though he knew he needed to draw it out of Guthrie. Lomax even encourages his interviewee to drink more to loosen up his memory.

These four interview CDs alone ought to be required listening in any American history class. But the lessons continue with Bonneville songs, which include the original version of “Pastures of Plenty,” along with others he wrote to document building the Grand Coulee Dam and bringing electrical power to the masses. The documentary, “Roll On, Columbia: Woody Guthrie & the Bonneville Power Administration,” puts further context on that rather remarkable project — not just the dam, but the fact that Guthrie wrote nearly a song a day for 30 days. Made in 1999 by Michael Majdic and Denise Matthews, it features many central figures in Guthrie’s life, including children Nora and Arlo, first wife, Mary, and Pete Seeger.

The radio dramas and songs for the Office of War Information (“Whoopy Ti-yi, Get Along, Mr. Hitler”) are downright funny, even though many deal with the serious issue of venereal disease. (In “V.D. Seaman’s Letter,” he sings, “With syphilis my cargo, I’ll dock in your harbor no more.”)

Unlike some aural documents of its kind, this isn’t dusty, scratchy history (thanks in part to Paul Blakemore’s restoration and remastering). It’s living still – not just in Guthrie’s words and music, but in the truth of his observations and, sadly, the awareness that, despite every supposed advance we’ve made, little has changed. Religion and racism still divide us, political shenanigans repel us, environmental threats overwhelm us, the rich get richer, the poor get poorer, and sometimes, the only way to deal is to sing another song.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.