Videos by American Songwriter

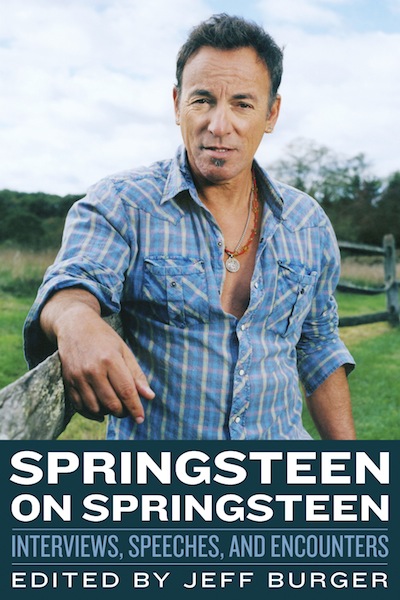

In this exclusive excerpt from Springsteen on Springsteen: Interviews, Speeches, and Encounters, Steve Turner of the NME turns the “Next Dylan” paradigm on it’s head. You can buy the book, a collection of fascinating interviews and articles from 1973 to 2012, here. Read our review here.

Steve Turner | October 6, 1973, New Musical Express (Uk)

“I think I was the first British journalist to see him,” said London-based Steve Turner, who talked with Springsteen in Philadelphia in June 1973 for an article that appeared about four months later.

While Springsteen had already spent years performing in clubs in New York City and New Jersey, this was still quite early in the game. Bruce was just twenty-three at the time of the interview, and his debut album, the Dylan-influenced Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J., had been out for only six months. Sales had been unimpressive and while many reviews overflowed with praise, others mixed plaudits with putdowns. In Rolling Stone, for example, Lester Bangs called Springsteen “a bold new talent” but also described the singer’s vocals as “a disgruntled mushmouth sorta like Robbie Robertson on Quaaludes with Dylan barfing down the back of his neck” and implied that while the lyrics seemed clever, many of them “don’t even pretend to” make sense.

Turner wasn’t too impressed, either. Prior to his meeting with Springsteen, he told me, he was in New York, where he saw the recently released film Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid, which starred Dylan and featured his music. “I was disappointed that Dylan wasn’t doing what I thought he should be doing,” Turner said. “There hadn’t been a really good album from him since 1967 and I thought we’d lost him. A friend of mine, Mike O’Mahoney, was handling international publicity for CBS and he tried to sell me on the idea of Bruce Springsteen, who was apparently the ‘new Bob Dylan.’

“I didn’t want a new one, I wanted the old one, and I have to admit that the songs on Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J., irritated me because they seemed to self-consciously emulate

Dylan’s technique of rubbing nouns together (‘ragamuffin drummers,’ etc.). You didn’t get a new Dylan, I reasoned, by copying the old one.

“It was Mike [O’Mahoney] who took me down to Philadelphia to see Springsteen in action at the Spectrum,” Turner continued. “My clearest memory is not of the concert—where he supported Chicago and was not a big hit with its fans—but of this unassuming boy in the dressing room wearing a sleeveless T-shirt and his manager, Mike Appel, who seemed to do all the talking.”

Perhaps partly for that reason, Turner didn’t elicit many quotes from Springsteen. But there’s enough here to sense the strength of the artist’s early ambition, not to mention the way he affected some early backers, such as manager Appel and Columbia’s John Hammond, who had signed him to the label. —Ed.

* * *

“Randy Newman is great but he’s not touched. Joni Mitchell is great but she’s not touched. Bruce is touched . . . he’s a genius!” Manager Mike Appel is talking in the dressing rooms of the Spectrum stadium in Philadelphia. His artist, Bruce Springsteen, has just finished a forty-minute opening set and Chicago is tuning up in the room next door.

“When I first came across Bruce, it was by accident,” he says, “but when I heard him play I heard this voice saying to me, ‘superstar.’ I couldn’t believe it. I’d never been that close to a superstar before.”

Not wanting to miss the chance of being Albert Grossman for the seventies, Appel took acetates of Springsteen straight to Columbia Records in New York. There he played them to John Hammond, the man who signed up Bob Dylan and Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday and Tommy Dorsey and Woody Herman.

Also, they were played to then-president Clive Davis. According to Appel, they needed to hear only one track before signing him up. [Other interviews suggest that Hammond decided to sign Springsteen after seeing him perform, not after hearing the acetates. —Ed.]

Springsteen’s a hungry, scrawny-looking guy. There’s definitely some- thing very Dylany about his whole being, about his curly hair and his scrub beard . . . and, I must say it, about his songs. It’s a comparison a lot of people are going to draw because of the connections with Hammond, the looks, and the highly influenced style of writing.

By this time, the man himself must be regretting the resemblances because the surest way of killing a man these days is to liken him to the late Bob.

Too many people have been primed to walk into those boots only to find they didn’t fit. After all, no one wants “another” of anything we once had, because we still have the original in our collections.

The other fault with PBDs (Potential Bob Dylans) is that people choose them on looks and sound alone, thinking that’s what made BD into BD. It wasn’t. BD filled the psychological need of a generation. Where there isn’t a psychological need, there’ll be no BD or, indeed, no PBD.

The Beatles too came at just the right time in history and filled an await ing psychological vacuum. To think it was their music, or worse still their lyrics, that made them the phenomenon they were is to be totally naïve.

We were the phenomenon . . . our need for them was the phenomenon . . . and they passed the audition to play seven years in the starring role of Our Psychological Need.

Now the million and one intricacies that make up a moment in history have changed. It may never happen again as it did between ’63 and ’70. To expect another Bob Dylan or another Beatles is like expecting a reunion ten years after any event to be exactly the same as the event itself. No way. History itself would need to be reconstructed for such a thing to happen.

Nevertheless, BD or no BD, Springsteen is a good ’un. His songs are crammed with words and multiple images. “He’s very garrulous,” agrees Appel. Onstage he’s powerful and confident. There’s a charisma there that doesn’t occur with many people.

His allegiance to Dylan is evident in the songs. They’re mostly stories of a crazy dream-like quality. Where Dylan had peddlers, jokers, and thieves, Springsteen brings us queens, acrobats, and servants. Where Ginsberg gave us hydrogen jukeboxes and Dylan gave us magazine husbands, Springsteen has ragamuffin gunners and wolfman fairies.

Compare his use of adjectives, too. Dylan used “mercury mouth,” “streetcar visions,” and “sheet-metal memory.” Springsteen comes up with “Cheshire smiles” and “barroom eyes.” Another notable likeness is in their use of internal rhymes.

Some of Springsteen’s numbers almost come over as direct parody.

Just for the record, other PBDs of the last couple of years include Kris Kristofferson, John Prine, and Loudon Wainwright III. Both Kristofferson and Wainwright are the property of Columbia Records . . . which recently lost the services of Bob Dylan. Now, I don’t want to start drawing conclusions but . . .

Bruce Springsteen is twenty-three years old and comes out of New Jersey. He first started playing music at age nine under the influence of Elvis. At fourteen it really hit him. “It took over my whole life,” he remembers. “Everything from then on revolved around music. Everything.”

Two years later, he was playing regularly at the Café Wha? in Greenwich Village. “I was always popular in my little area and I needed this gig badly.

“I didn’t have anything else. I wanted to be as big as you could make it . . . Beatles, Rolling Stones.”

For the next eight years, Springsteen played in bands. Steel Mill . . . Dr. Zoom and the Sonic Boom . . . and finally his very own ten-piece band, which he named after himself. After two years, the numbers began dwin- dling. Nine, seven, five, until it was Bruce Springsteen—solo artist.

Then: “I just started writing lyrics, which I had never done before. I would just get a good riff, and as long as it wasn’t too obtuse I’d sing it.

“So I started to go by myself and write these songs. Last winter, I wrote like a madman. Put it out. Had no money, nowhere to go, nothing to do. Didn’t know too many people. It was cold and I wrote a lot . . . and I got to feeling guilty if I didn’t.”

At this time, he met up with Appel, who in turn took him along to meet Columbia’s John Hammond. Appel is a fast talker and took it upon himself to sell Springsteen.

Hammond listened and began to take a dislike to this salesman. In contrast, Springsteen just sat, very quiet, in the corner of the office.

“Do you want to get your guitar out?” asked Hammond. Springsteen did. He began playing “Saint in the City.”

“I couldn’t believe it. I just couldn’t believe it,” recalled Hammond.

In Hammond’s opinion, Springsteen is far more developed now than Dylan was at the corresponding point in his career. He feels that Dylan had worked hard at creating a mystique even before he signed with Columbia but Springsteen is . . . just Springsteen.

His first album for Columbia has been Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. Reviews have been ecstatic. It marks a strong contrast from the way John Prine was handled. In his case, it was the publicity handouts that had the ecstasy, in the hopes that they could set the press on fire.

“In the tradition of Brando and Dean” was how they sold him.

With Springsteen, Columbia is restraining itself and relying on understatement.

Mike Appel believes totally in Springsteen. “I’ve sunk everything I’ve got into him,” he tells me. And if he doesn’t make it . . . ? Appel demonstrates by holding his nose and flapping around in an imaginary ocean.

* * *

This excerpt from Springsteen on Springsteen: Interviews, Speeches, and Encounters by Jeff Burger is printed with the permission of Chicago Review Press. For more information, please visit www.ipgbook.com.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.