Videos by American Songwriter

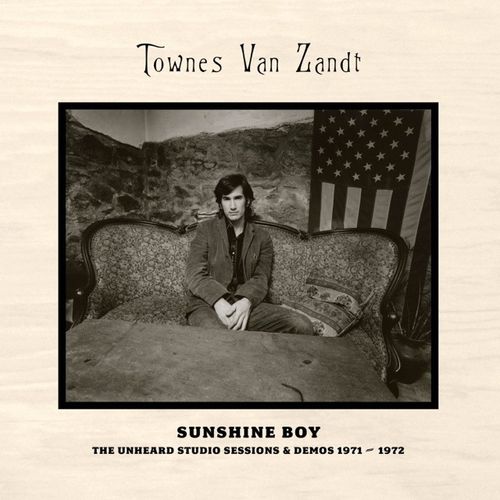

Townes Van Zandt

Sunshine Boy: The Unheard Studio Sessions and Demos 1971 – 1972

(Omnivore Recordings)

Rating: 5 stars (out of 5)

The Colin Escott-penned liner notes for the newly released collection from Omnivore Recordings, Townes Van Zandt – Sunshine Boy: The Unheard Studio Sessions and Demos 1971-1972, needs but a few words near the essay’s end to sum up how most Van Zandt fans will feel about this double-disc offering.

“The alternate versions are like seeing a friend in a new light. The new songs are simply good to have when it seemed as if the barrel was empty.”

When it comes to Van Zandt, it’s tough to argue with such a simple but loving sentiment. And to a vast extent, this release is a triumph and a resplendent showcase for Ft. Worth, Texas-born Van Zandt, who died on New Year’s Day in 1997. The years of 1971 and 1972, from which these selections are culled, were part of a wonderfully genius period of time for the man who’s legend has become much greater in death than it was during his life, when his name managed to cut a formidable figure in only some circles. From 1968 through 1972, six studio albums yielded many of the songs that are now considered to be indispensable elements of the theoretical country songwriter’s handbook, especially south of Tennessee. Some of these songs are featured in beautifully stripped-down manners. And in a few cases, as with “To Live is To Fly,” a song is offered once on each disc, offering different versions of the familiar tune.

In certain scenarios, putting cuts of mere demo-recordings onto an album would be something that only material-starved completists of that artist might be interested in. Sunshine Boy, however, can serve as a TVZ starter-kit, with a few compelling nuggets for the long-time fans thoughtfully added. Such is the case, thanks to an expertly curated track-list where covers, classics and lesser-known tunes are seamlessly woven together.

While it’s tough to feel as though another version of “Pancho and Lefty” is really needed, it doesn’t take long to realize that Van Zandt’s signature tune, without strings, horns and the dated production, indeed makes this one that should find its way beside the popular versions of Emmylou Harris and Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard. This take on his signature song beams with the warmth of a Cali-country tune that would’ve fit into the catalog of Buffalo Springfield quite nicely.

The two versions of “To Live is to Fly” (drums bring a bit of punch to the version on Disc One and Disc Two offers the superior, strictly acoustic take) and “You Are Not Needed Now,” also prove that simple, clean instrumentation and engaging stories, that never fail to move the listener, are timeless.

Van Zandt’s voice, aside from the words themselves, is the key- and underappreciated – instrument. The plaintive honesty that emanates from his singing lends the songs simplicity that many artists would have a tough time dealing with successfully.

It’s in the blues realm Van Zandt loved so dearly where he lets his howling flag fly. The almost-spoken flatness in both different-but-awesome takes on “Mr. Mudd and Mr. Gold” is amped up in a greasy, spirited rendition of “Who Do You Love.” The same can be said for perhaps the record’s brightest revelation, the previously unheard, country-blues stomper “Diamond Heel Blues.”

Yodeling is a jubilant vocal vehicle in the re-working of Jimmie Rodgers’ gem “T is For Texas.” More than any other track out of the 28 offered, this cover finds Van Zandt happy and seemingly free of the whiskey-drenched demons he so often entertained. On the darker end of that spectrum however, another regular cover selection of his provides a glimpse into the bleakness that would eventually envelope him beyond rescue.

The two takes on the Rolling Stones classic “Dead Flowers,” which bares the obvious, ominous mention of “a needle and a spoon,” show a somber Townes who raises his voice for only a brief moment during the chorus of the version on Disc Two, which, thanks to the piano and distinctive drum, sounds as though he recorded it with The Band in Big Pink. It’s also tough to look past the after-life ethereality of “Heavenly Houseboat Blues,” which Van Zandt wrote with Susanna Clark. On this album, the honky-tonk hymn carries a melody that closely resembles that of the Carter Family classic, “No Depression in Heaven.” Van Zandt’s tumultuous life proffers many opportunities to argue about whether art imitates life, or if it’s the other way around.

Adding to the fly-on-the-studio-wall feel of the proceedings, we can hear Van Zandt count-off before starting a couple of songs. That intimacy is why this record is, well, important. More people than ever want to grow close to this artist that isn’t any longer among us.

Because of the mastery Van Zandt displayed in his living years and the mythology that has developed since his death, Sunshine Boy is more than a new album of ragged tid-bits pulled out of an engineer’s closet. Each song forces the listener to stop and wonder where Van Zandt’s mind was taking him as a specific song was cut, or what might’ve been “really meant” when a certain line was sung. Such unavoidable thoughts and questions give this beautiful double record the weight of an historical document.

Unsurprisingly, Van Zandt’s own words from his pristine, yet bare-bones take on “Tower Song” sum up this album’s beauty and pain, and perhaps too, the dismal end of his life on Earth.

“You built your tower tall and strong, don’t you see, it’s got to fall someday.”

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.