Videos by American Songwriter

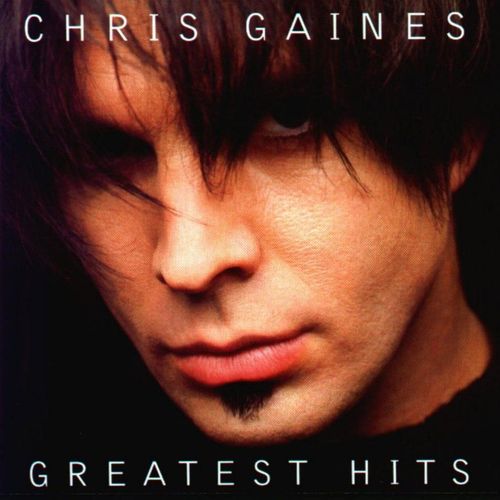

In late 1999, Garth’s Chris Gaines album came out and failed. By “failed,” I mean sold more than two million copies, charted as the second best-selling album in America, and spawned a Top 10 single.

Garth took a bad beating for this. He became a punch line for doing something way more successful than anyone I’ve ever met has ever done. People made fun of him, and the lost momentum meant that he never even got to make the Chris Gaines movie.

The last time I’d been around a failure as popular as Chris Gaines, it was my friend Darius Rucker, who fronted a band called Hootie & The Blowfish. I opened a show for Hootie in front of four hundred people at a little club in Atlanta in early 1994, and by that summer I was opening for them in front of ten thousand people in Colorado. It got bigger from there. Their first album sold more than ten million copies. Everybody had it. And then in 1995, the year Hootie outsold everybody, even Garth Brooks, Darius came to my show in South Carolina.

Afterward, he came up on the bus with me, Jack Ingram, and Will Kimbrough and told us there was a party going on at his house, and we were all invited. He wanted to show us Hootie’s next record, which they’d just finished.

The house wasn’t a mansion, but it was a nice-sized place in a nice neighborhood. We walked in, and the first thing I noticed was that the party seemed a little out of control. Two girls went dashing by as we were walking through the foyer. I was struck by the chaotic nature of the whole thing, and I no ticed there was a security guy in the kitchen who didn’t seem to be taking an active interest in calming things down.

I asked Darius if the party was for any particular reason, thinking it might have been his birthday or something. He said that it was actually a party they’d had the previous weekend and that they were having trouble winding it down.

We went down to Darius’s room to listen to the new re- cord, and he had a big walk-in closet there. He and Hootie had made a famous music video where he was wearing a Dan Ma- rino football jersey, and I said, “Is that closet where you keep the Marino shirts?” He laughed and said, “Actually, yes.” And as he went to show them to me, we could see four feet behind his clothing.

Darius ordered the feet to come out, and they were attached to two college boys who were in his closet. Darius said, “Go upstairs,” and they did.

We went further into his room, and there were candles everywhere. And there were two girls in his bed, and he didn’t know either one of them. They were asleep. He told them to wake up, but they didn’t. We just left them there, sleeping.

And then we sat on the floor, by the edge of the bed these girls were sleeping in, and we rolled a joint and put on the follow-up to the biggest-selling album of 1995, Cracked Rear View. We listened to the whole record, and liked it, and then when we got up to leave Darius called for the security guy to get the girls out of his bed so he could go to sleep himself. He wasn’t wrapping up the weeklong party, just putting someone in front of his door so he could be by himself for awhile. For all I know, he got up in the morning, grabbed his golf clubs, and marched through that same party.

How do you end a party like that? How did he get those people out? They were like rats, scurrying everywhere. But he didn’t seem bothered by it. The album he played for us that night, Fairweather Johnson, was a colossal failure because it only sold four million copies. Darius and his band had to spend the second tour of their lives dodging people who were telling them something was going wrong. That’s when the party started to dwindle, and all those kids were gone by the third album, which only sold a million.

* * * *

After Garth Brooks’s multi-million-selling failure on the Chris Gaines album, a lot of people laughed at him. He even went on Saturday Night Live and made fun of himself, but that didn’t help. It was open season on Garth. Meanwhile, I was about eight months into my new life as a rambling, storytelling folk singer. Any story I could find that had an element of Arlo Guthrie’s “Alice’s Restaurant” in it, I honed in on and worked on it just as hard as I would work on a song. With Garth taking a public flogging, I thought maybe there was some kind of story I could tell about him. I knew I could tell the story before or during the part of the show where I’d play “Alright Guy.”

And so I made up a story that started with the phone call from Garth. And most of the story is pretty true. But at some point, I realized it would be beneficial for me, in my attempt to get laughs at my show, to pretend I knew in real time what a disastrous idea this Chris Gaines thing was. In the story, I played along and told Garth that it was a great, smart idea, knowing that he was going to fall on his ass.

That was not in fact anywhere near true.

The truth was that I thought it was going to be successful, and thought it was cool, and had hopes that it was going to do well.

In fact, I still don’t think it was stupid. I think it was smart of Garth Brooks to make a creative choice that resulted in sell- ing millions of albums. Sign me up for that kind of stupid.

No matter the truth, though, I decided to exploit the idea that not everybody likes Garth Brooks to my own end. And I told myself that Garth wouldn’t be hurt by something like that, because he was so successful.

That’s a crock.

It’s a crock that I think prevails in this country: we bully the people who entertain us. We get on the computer and bully them. We buy magazines with pictures of them where they look fat or drunk or imperfect. And we suppose that those peo- ple’s success excuses our meanness.

I say this as somebody that this is, for sure, not happening to; I’m not popular enough to get bullied in this way. I’m just unpopular enough to mostly get encouragement.

In my young life, Garth and Jimmy Buffett were the people I got to be around who were so powerful that other people didn’t treat them like people. They got treated like a television show, or like a football team or a wrestler. And I got caught up in that and wound up telling a story that took the piss out of a guy who had shown me kindness and graciousness, and who gave me—with no strings, no contracts, with an apology, even—ten thousand dollars.

That’s embarrassing. It’s a shame wisdom comes so slow. It’s what makes life hard to look back on. It’s the downside to giving everything in your life to this idea of suspended adolescence: you find yourself doing immature things at awkward ages. In my case, it involved being a douche to someone who was cool to me, just to look cool in front of other people. I did this when I was in my thirties, and in truth I probably already had the wisdom to know better. I just chose to ignore it.

A couple of years ago, I saw Garth at a Country Music Hall of Fame thing, and he called out to me by name, immediately. Then his wife, Trisha Yearwood, started telling me how much Garth liked me. I assumed he hadn’t heard my little stage story, or that if he had he wasn’t bothered by it. It doesn’t matter whether he heard it or whether he was offended by it. A bully is a bully. Putting negative energy into the universe is just what it is, and it isn’t art and it isn’t funny. It’s a crock of shit, and it’s mean.

By the way, every time I’ve told someone the story of Garth remembering my name and giving me money, it’s been topped. Somebody’s got a better one. There aren’t a lot of stories out there about me remembering names and giving away money, but I’m going to try to get better at that.

Buy Todd Snider’s I Never Met A Story I Didn’t Like here.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.