Videos by American Songwriter

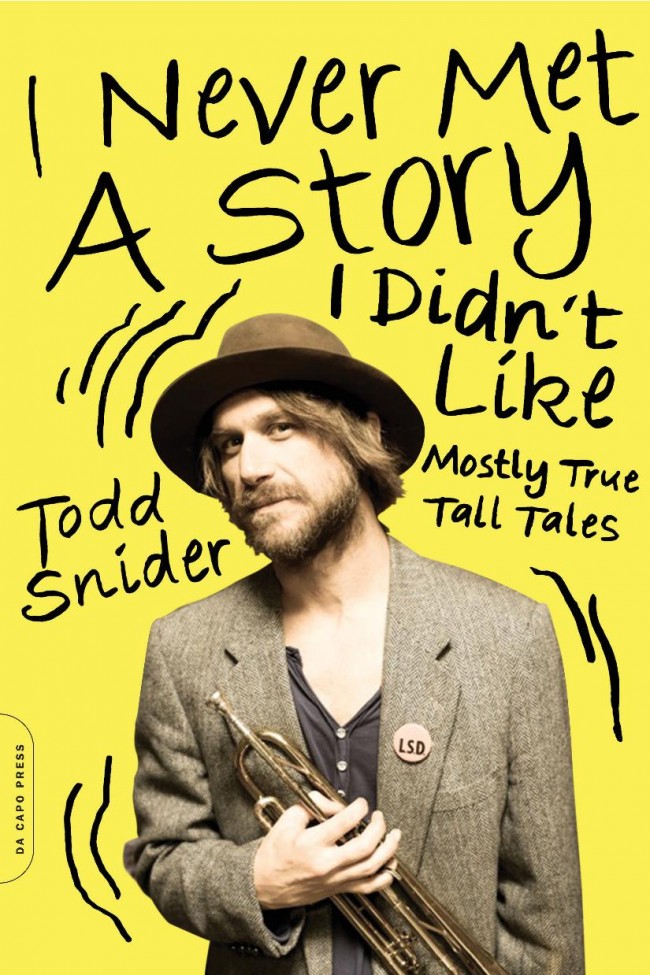

Todd Snider has always been a natural storyteller, both in his lyrics and on the stage. So it makes sense that his new book I Never Met A Story I Didn’t Like: Mostly True Tales is a masterpiece of storytelling. In this hilarious memoir, the East Nashville songwriter recounts his run ins with Jimmy Buffett, Hunter S. Thompson, Slash and several other colorful characters, and expands on the many yarns he likes to spin between songs.

Here’s an exclusive excerpt. . . a tale of Garth Brooks, alter-egos, humility and Hootie and The Blowfish.

* * * *

Is This Really Garth Brooks?

In 1999, I’d just moved into my house in East Nashville, and the only person who knew the phone number was the singer Mark Marchetti. Mark liked to call and pretend to be other people, and I always played along. It was fun for him, and for me; it was a great way to pretend to talk to Keith Richards, Hank Williams Jr., or Margaret Thatcher.

On this day, it was Garth Brooks, the biggest selling solo artist in the history of music.

“Yeah, shit man, what’s up, Garth?” I said.

Then he said a couple of other things, and I said, “Seri- ously, what’s up, man? Stop fucking around.” I didn’t want to play anymore. I wanted to know why Mark was calling me.

But Mark didn’t catch my drift. Because, as it turns out, Mark wasn’t on the line. “Mark?” I said.

“No,” not-Mark said. “Garth.”

Garth Brooks was talking to me and had been doing so for a couple of minutes. I gracefully shifted the conversation in light of this new information. “Goddamn,” I said. “I thought you were fucking around, and I wasn’t listening to any of the shit you said. Can you start over?”

Without complaint or any hint of irritation, he started over. He told me he was making a movie, and he wanted to put my song, “Alright Guy,” in the sound track. He told me the story of this character he was playing in the movie, a pop singer called Chris Gaines, and how he’d created an entire history for this character, and he wanted “Alright Guy” to be a song that Chris Gaines sang in the 1970s. Since the song had a few lines that were specific to the 1990s, he wanted to work with me to change some of the words, but he made it very clear that he was not going to take any credit or money for making those changes. In Nashville, when a singer tells you he wants to change some words, he usually means he wants to cowrite a song that you’ve already written and take half the dough. This wasn’t the case here, though, and everything Garth told me about the movie and the sound track—which was going to come out before the movie was even made— sounded brave and cool. Most of the time, singers play movie characters that are just like themselves—Prince in Purple Rain or George Strait in Pure Country—but Garth was going out on a limb, creating a new persona and finding songs that didn’t sound anything like the hits he’d recorded. The closest thing I could think of to what he was talking about was Kris Kristofferson in A Star Is Born, and I love that movie.

Also, I loved Garth Brooks. I was, and am, a very big fan. I think Garth Brooks fucked up country music for a while, through no fault of his own: he made music so good and so successful that tons of people came along after him trying to imitate what he did. Garth fucked up country music like Kurt Cobain fucked up rock.

Garth was a fascinating, comet-like figure. He hasn’t made a record in a decade now, but he’s interesting enough that people to this day ask me about my brief time knowing him a little. It’s a great story to tell. He has a powerful, Michael Jackson–like presence. I should tell the story sometime about how he called me up and I thought he was my friend Mark.

Because of Garth’s massive success, there’s a bit of a push and pull in Nashville about him. When you sell more records than anyone has ever sold, you tend to make more people jealous than have ever been jealous of a singer. You don’t have to be in town for long before you’ll hear somebody say something jealous about Garth Brooks, and then you’ll find that there’s somebody within earshot of the jealous person saying something nice about him. The stories of Garth helping people are unbelievable, though he won’t tell them himself. I know for a fact that he’s bought homes for people and paid off hospital bills for family members of people he cares about. He’s one of those rare people whose capacity to help is equaled by his willingness to help. He’s concerned about other people, and he demonstrates that concern in ways that make those people’s lives easier.

I didn’t know Garth when he called, but I knew all his songs, and I knew his reputation. And I was thrilled that he was considering recording one of my songs. Over the next few weeks, we batted lyric ideas around three or four times, and we settled on some stuff that worked. We’d send the song back and forth on fax machines. I had a fax machine, but still didn’t have a computer. Then one Saturday, he called and said, “What are you doing?” I wasn’t doing anything, and he said, “We’re recording ‘Alright Guy’ tonight. Can you come by the studio?”

Could and did. The studio was in a mansion out in Franklin. When I got there, everyone was eating Chinese food. Tommy Sims—a great bass player who wrote a song called “Change the World” for Eric Clapton—was there. And I was mesmerized by the producer, whom I immediately recognized as Don Was, because Don Was had produced . . . wait for it . . . The Rolling Stones. I was already starstruck before Garth walked up and introduced himself. He said, “I thought you had red hair,” because he’d seen me on the Austin City Limits television show, and I’d dyed my hair red for that show. It wasn’t supposed to be red. It was supposed to be dark brown. My plan was to look like John Fogerty, but instead I ended up looking like the guy from the movie Dumb and Dumber. “You look like that guy from Dumb and Dumber,” people would tell me, and I would insist on Fogerty. So now that the red had worn off, Garth Brooks and Don Was thought I’d died my hair blonde.

Garth took me aside and said, “C’mon, I’ll show you what we’re doing.” He and I went into the control room while everybody else ate their Chinese food.

He said, “I don’t know if you like commercial music at all. You ever listen to any commercial stuff?”

Like it? Listen, I know I’m not the most commercial artist in the world, but I didn’t think I was so uncommercial that Garth Brooks would suspect that perhaps I had never listened to the radio. I mean, my God, sometimes it’s not so much the heat as it is the humility.

Garth showed me some of the songs they were working on, and I thought they sounded cool. I really liked one called “It Don’t Matter to the Sun,” and I noticed that this stuff was a long way away from the country songs he sang on the radio. Then everybody got done with their Chinese food, and we recorded “Alright Guy,” with Garth singing and me playing guitar and harmonica. We recorded several takes, and at the end of one of the takes, Garth was ad-libbing at the end, and he said, “I think I’m alright, fuck you.”

When we got done, Garth let me take a mix of the song home. I said, “Can I have the one where you say ‘Fuck you’?” He said, “Yes, but if I ever hear that version somewhere else, it will hurt my feelings and that will be the end of our friendship.” He was serious enough about the way he presented himself to the public that it would really bother him to have that “fuck you” out in the world, and I promised him I’d keep that version to myself. He was a nice, kind person, and I didn’t want to do anything to hurt his feelings or his image. He listened closely to everyone in the room and had a way of directing his attention to you that was free of distraction. I remember thinking that he reminded me of what I imagined Bill Clinton was like.

Garth was a lot less music business–oriented toward me and a lot gentler and more poetic toward me than some of my supposedly art-first songwriter friends. My television and my magazines had told me that “alternative country” peo- ple were altruistic and art oriented, and that commercially successful country music people were money-grubbers. But as it turned out, I didn’t come away from that studio disappointed with Garth; I came away from it disappointed with my television.

Word started to get out that Garth Brooks had cut my song, and my friend base doubled pretty quickly, while I started thinking of what I should buy with the money that would come from Garth recording the song. Should I buy something stupid? Isn’t that what you do? Maybe an animal or something? Tom T. Hall has peacocks. Should I get one? Or maybe a monkey? I’ve never trusted monkeys, but maybe I could learn.

Time went by, and Garth’s people got all my publishing information, and I kept debating the merits of monkeys versus peacocks. And then Garth’s mother got sick, and Garth made a decision that he was not going to do anything to even remotely challenge his mother, whom he loved very much. One thing that his mother was uncomfortable with was a line in “Alright Guy” about smoking dope. So Garth called me, told me “Alright Guy” wasn’t going to be on the record, and told me why. And he apologized. He did not have to do any of that. He had nothing to be sorry about. He had every right to put any song on his record and to leave any song off. Singers don’t have to even communicate with writers. I wrote a Top 20 hit for a singer named Mark Chesnutt, and I’ve never even met him. Nobody called to tell me he’d recorded it. I heard it on the radio. Garth had given me a once-in-a-lifetime experience of being in the studio with him, Don Was, and all the others. I was grateful, and I told him that.

A week later, there was a check in my mailbox for $10,000, with a note from Garth that said, “Sorry, man.”

If you’re reading this and thinking, “Well, that was the decent thing to do,” I’m telling you that you’re wrong. I’ve been in this thing for twenty years, and this was ten thousand times more than the decent thing to do. This was unheard of. He owed me nothing but paid me $10,000, and apologized for that. The ten grand was on top of the thousands he’d already spent recording the song in a world-class studio with world-class musicians.

So if we’re pondering the decent thing to do, the decent thing would have been for me to rip up that check, send his mother a “get well” card, and spend the next few days walking around the neighborhood telling everyone what a swell guy Garth Brooks is.

Instead, I cashed the check and wondered what to name my monkey.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.