Within the sphere of U2’s 40-plus year career, The Edge’s razor-sharp and transcendent riffs have saturated every reminisce, trance, and sonic boom within the band’s many incarnations. Once christened “The Sonic Architect” by Jimmy Page, The Edge has remained a vital part of the vertebrae within the band’s sound, dynamics, and lyrics, with a hand in co-writing the majority of the band’s catalog.

Videos by American Songwriter

Beyond U2’s periphery, The Edge and U2’s Bono have also written songs outside of the band‘s long directory of songs, including Roy Orbison’s In Dreams track “She’s a Mystery to Me” (1998), Tina Turner’s sultry 007 theme song “Goldeneye” (1995), and Willie Nelson’s “Slow Dancing,” in 2003, along with “Where the Shadows Fall,” featured in Nelson’s 2018 film, Waiting for the Miracle to Come. Both also scored the London stage adaptation of A Clockwork Orange in the early 2000s, before writing and composing the 2010 Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark musical.

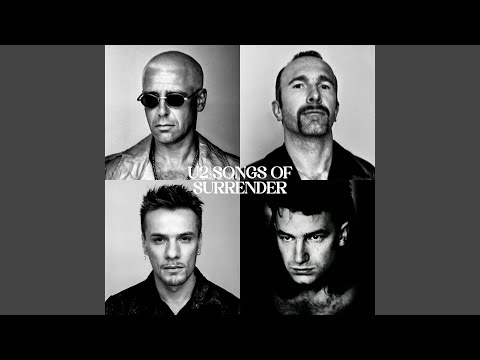

Working apart from bassist Adam Clayton and drummer Larry Mullen Jr., The Edge, and Bono recently time-traveled back to the band’s four-decade-plus collection of songs, reverting tracks to demo-like form and rebuilding them from scratch on U2’s 2023 album Songs of Surrender.

The Edge recently chatted with American Songwriter about producing Songs of Surrender, the band’s history of song originating in melody and emotion before lyrics, how “Bongolese” often helps the band finish a track, and some of the “gifts” they’ve received over time.

American Songwriter: At the beginning of U2, everything was more jam-based and improvisational. How has the band’s collective songwriting “system” shifted over time?

The Edge: There are so many ways that we write songs. Sometimes I’ll start with a drum beat, and I’ll just build it up where I’ve got a very clear intention for a certain kind of outcome. And sometimes it might be just a guitar part or a chord progression that is particularly intriguing. And we’ll start developing that idea. Early on, we used to jam together. Sometimes we get some really cool beginnings that way, but these days, it tends to be beginnings that I generate and bring to the others, either close to complete, or in some some cases very rough, like just a starting point.

I’m really trying to develop close-to-finished song ideas, if not lyrically, certainly, musically, so that we’ve got something very clear to start with. But that doesn’t mean that it’s sacred. I’m always open to a better idea, and I think that’s the key to our process, that we sort of take personal ego out of it. It becomes about what’s the best idea in the room, and that can come from the others, or by changing the way that they’re playing the songs or Bono will throw ideas at me all the time, which I incorporate. That’s the key. What’s the best in the room?

AS: Working within that structure, what are some of the compromises you face when it comes to lyrics?

Edge: We tend to give Bono free rein with the lyrics because he’s got to sing it. I’ll throw lines in and help steer him through a logjam of lyric writing. With the music, I know Bono’s really a top-line specialist. That’s where his expertise is, so those top-line ideas can be for his melodies. I’m more about the emotional weight that is contained within the chord progressions, chord shifts, and the sonic terrain. So for me, it’s always about engaging with an emotional feeling in the track.

We’d often finish a song and there’d be no lyrics, or we’ll have a melodic track of Bono singing, but there are no finished words. We call that “Bongolese,” where he’s singing without a finished lyric. So he established the melodic idea, but then the actual content we start drawing from the music. The music, again, tells us kind of what this song is about.

“One” is a great example. That song we pretty much had it musically figured out. The first idea was the concept of “One,” but then the lyrics took a little while to come into focus. Occasionally there’ll be a more fleshed-out lyric, but in most cases, the lyric is the final thing.

AS: Has it always been that way for the band?

Edge: Yeah, even on our first album (Boy, 1980), we’d been performing some of those songs live for months, and there were still no finished lyrics. In the final phase of recording, Bono was in quite a high-pressure situation. The songs were pretty much figured out. We recorded the music without a huge amount of trouble and had a lot of fun without overdubs, working with Steve Lillywhite. Adam [Clayton] actually had a lot of fun with Steve on some bass overdubs and strange atmospheric things that they were doing, but Bono was kind of locked in the tower of the song trying to finish the lyrics. I felt for him. It was a real pressured time for him. It’s always been like that since the beginning.

AS: You mentioned Steve, and U2 has always had this revolving door of producers like (Brian Eno, Daniel Lanois, Flood, etc.) Where do they come into play when the band has a sort of musical base?

Edge: They’re a crucial element, because the hardest thing to hold on to when you work in the studio, particularly as we often do, is using the studio as a songwriting tool. We’ll have a raw track, and then we’re sort of trying to, as I say, follow the clues to get to that essential version of what might be a very raw beginning. Having producers around that have a great understanding of music and our band, to be objective judges and to kind of help steer that process is really important. I really value and credit our various producers with being essential to us getting to the early versions of the songs.

In this reimagined version (Songs of Surrender), they’re not involved directly. I was producing myself with [some help from] Bob Ezrin, but this collection would not have been possible without the help that we had in the definitive versions, the earlier versions, from these great producers.

AS: It’s amazing how far some songs can be stretched, whether it’s into pop, or adding an orchestra behind, or just stripping everything back. It’s the sign of a great song. When you were revisiting these 40 songs, which ones had a greater transformation?

Edge: Some changed quite a bit in this sort of reimagining. With “If God Will Send His Angels” (Pop, 1997), it was quite an abstract piece of music over a groove that was borrowing from a kind of trip-hop tradition we were excited about at the time, but the chords were not clearly stated. It was like a bass groove, and then the lyric was a down sort of sentiment. So in this reimagining, I started from scratch with the music, and I started thinking about different chord progressions that could back that melody and change the chords radically. Then, Bono, as he’s singing, starts to go, “Well, I think this is too down. This isn’t resonating with me,” so he changed a few of the lines in the chorus, and now it’s this beautiful song, which is more in balance. It’s hopeful as much as it is a story challenge.

“Walk On” (changed to “Walk On Ukraine”), we radically changed, because it also felt that the original lyric, sort of lost its relevance to delay. We rewrote it using the struggle in Ukraine as the inspiration, and I think it so fits this moment.

It shows you that songs, they are alive, and they can be updated. Great poets do it all the time. [William Butler] Yeats, throughout his life, would revise and change stanzas in his poems, and if you go through a Harold Pinter production now, you’ll find scenes have been updated and changed. So it’s not unique to us, but I think giving ourselves the permission to do that was an important part of a kind of freedom we felt we had, and enjoyed, in making this work.

AS: You’re absolutely on to something. Rodney Crowell just released a book (Word For Word, 2022) and clearly stated that he has no problem revising lyrics over time.

Edge: I fully support that. (Laughs)

AS: When is a song ready for you? Can you hold it for some time, or do you need that release?

Edge: Sometimes a U2 song will be sitting there, and we are all convinced, for one reason or another, that it has not reached this sort of completion—something’s not quite there about it. We always find arguments around things that are almost there, almost great. If something is finished, and is great, it explains itself. It argues its own case. Whereas, something that’s not quite there, you’ll find people (within the band) taking a position on it. They either love it, or hate it. It’s almost a guarantee. If we’re in an argument about a song, it’s because it’s not there, so we’ll often put it aside.

That was true with “Every Breaking Wave.” We had early versions of that song with other sections, and it was much more complicated and big with musical motifs. In simplifying that song, just a few little changes in the chords, suddenly it comes into focus. If a song sounds writerly, you’re never going to love playing it live. It’s got to feel like it always was there, in its natural state. And that’s what I was trying for, this timeless quality, where you’re not thinking “Oh, this is clever.” It’s “Wow, this is reaching me.”

AS: You never want a song to sound intentional. On the flip side of these processes, have there been some of those magic moments when the songs just came out?

Edge: We do get gifts. I always think of “One” [Achtung Baby, 1991] as one of those gifts, where it was just an observation. Again, this is why having great producers around is so crucial. We had a song, which eventually became “Mysterious Ways,’” but at the time we were working on it in Berlin, it had no chorus. It was a groove, a great verse idea, and that was all we had. Bono went into the other room to work on chorus ideas for “Mysterious Ways.” I came back in and I was showing Adam what the chord changes were, and Danny [Daniel Lanois] goes “Let’s play those back to back,” so I played the two chord progressions back to back and we all just went, ‘Oh, that’s a great combination of sequences. Let’s try that out in the room.”

So we all barreled out to the recording room, and Bono got on the microphone, and we just rotated verse and chorus and within 20 minutes, this song arrived. Again, not with finished lyrics, but we could instantly tell there was something really powerful about this piece of music.

Another example would be “Kite” (All That You Can’t Leave Behind, 2000), where I just prepared the string arrangement, which I felt really lent itself to different chord progressions and changes. So I just laid it against a click track and Adam and Larry and I started playing over it. Then, Bono came out on the microphone, and the four of us developed all of the sections that became that final song. We had to do a bit of editing, but it was an improvisation that basically became the basis of that tune.

AS: In producing the album, did you feel any pressure around touching some of these songs again, particularly since so many are deeply etched in a certain way with listeners?

Edge: There was no pressure at all, particularly early on because there was no expectation for this. There was no record company release slot. There was no timetable. We were locked down and there was a spirit of fun and discovery and the spirit of it was quite a joyful experience, because the songs were already written, so you’re taking that stress out of it. We were very unpretentious about it. If something worked, we were happy. If it didn’t work, we’d just start again. I found that very liberating, and I didn’t find it a pressure at all, particularly once we had given ourselves permission not to be reverent about the original arrangements or versions. It was like a blank canvas in a great way. So it was really a good start to live in your imagination about how these songs could sound.

AS: I imagine that you’re also thinking about the live element and how a song translates there as well.

Edge: Our band is always about live performance. That’s really how we learned what a good song was because it’s the instant proving ground. You write a song in rehearsal, or at home, you come before an audience and you know, instantly what’s working or not. That was our kind of filter for the songs that we had and we knew the good ones. We knew the ones that weren’t gonna make it, and I retain that. Often when I’m sitting down to start something, I’ll start with this sort of thought exercise of “What is it that I would want to hear if I was in the audience,” now “What would I want to hear if I’m playing on stage.” I’m the one receiving it, and I find that’s a great starting point.

AS: You mentioned that by pulling some of these songs [on Songs of Surrender] back to basics or stripping them down, helped you find more dimension within them. Has this experience shifted the way you’re approaching some of the new songs (for the upcoming album) now?

Edge: I’m working on some more rock and roll tunes at the moment at home with drum loops and drum machines and trying to get a full band sound, but this is something that Steve Lillywhite has asked us many times over the years to do. When we’ve been playing our demos, he would say “Let’s just play it on acoustic guitar and just see how it will work.” And it’s amazing how stripping it down will really tell you what you’ve got because you can sometimes be fooled by the sonic power of the band.

It’s the melodic power and the emotional weight of a song, that really communicates, not the sonic power. We probably should do more of that. Off the back of this experience, I will be doing more of that, because you start to really appreciate the essence of what you’ve got when you strip everything away.

AS: What kind of songwriter are you today?

Edge: Now I’m much more aware and understand a lot more about what goes into a great song and a great arrangement. It’s to make sure that what if we were all together in the room working on something that is going to go all the way. To me, it’s like a process. I will play guitar piano all the time, you know, and I’ll be looking for new ideas that could be a little guitar, piano part, or just some chords. And it’s really building up from there. I don’t want to ever get to the point where it becomes too methodical in the sense of predictable.

I love approaching music in a naive sense of experimentation and discovery, more than for a format. I’m lucky in that my ear is very tuned to things that are powerful, both melodically and in terms of chord changes. I think that’s probably the greatest gift that we possess within the band is not necessarily knowing how to get there, but recognizing when we have hit on something. I can play something for Bono on the phone. If it’s really strong and powerful, he’ll hear it across the room, so I like keeping it in that way, so I don’t overanalyze our work. And I don’t overanalyze, even when I’m actually in the process of writing. I like to just use an instinctive, almost naive sense of mystery because, to me, it is so mysterious. It always is. If I knew how to do it, I’d be doing it all the time. So there’s also that kind of just showing up and being there, making yourself available for that inspiration is a part of it because we can’t dial in it. We can’t sort of dial it up. Sometimes it’s there. Sometimes it’s not.

Read our recent interview with The Edge from the 2023 American Songwriter May/June print issue HERE.

Photo by Jo Hale/Redferns

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.