As frontman of Iron Maiden since 1981, Bruce Dickinson has written a long line of songs for the band for nearly 45 years, along with seven solo albums from 1990 debut Tattooed Millionaire to The Mandrake Project in 2024.

Dickinson’s first solo release in nearly two decades since Tyranny of Souls in 2005, The Mandrake Project revolves around a multitude of subjects—including death, rebirth, and eternity—and marks his 30-year partnership with musician, songwriter, and producer Roy Z, who has worked with Dickinson on nearly every album since Balls to Picasso in 1994.

The Mandrake Project, which started more than a decade earlier—and dates as far back as 23 years when the track “Sonata (Immortal Beloved)” was first written—is one Dickinson continued to work on after beating throat cancer in 2015. The album will continue for years to come with an accompanying comic series by Z2 Comics. The 12-part series, written by Tony Lee and illustrated by Staz Johnson, presents an “epic saga of opposing forces battling to use the powers of science and magic to gain control of immortality,” according to Z2.

Videos by American Songwriter

“I think this is the most extraordinary record I’ve ever made,” Dickinson told American Songwriter.

Dickinson spoke to American Songwriter about how writing some “not-nice, abusive lyrics” for A Nightmare on Elm Street unexpectedly pushed him into a solo career, where he finds motivation in songwriting now, and working outside the “Maiden bubble.”

American Songwriter: When you were working on Tattooed Millionaire, how were you approaching writing your own songs as a solo artist?

Bruce Dickinson: That album [Tattooed Millonaire] was entirely opportunistic because I had no real idea if I was going to do a solo record. My friend Janick Gers—who is now in Maiden but wasn’t back then—was going to sell his equipment, give up music, and become a sociology teacher. Then I got offered this song, on A Nightmare on Elm Street 5 [‘The Dream Child‘] movie soundtrack, and I went, “Oh yeah, I’ll do that. I’ve got something in mind.” I had nothing in mind, no songs kicking around in my head at the time whatsoever. But there was a recording budget, and I thought that with the money I make, if Janick wanted to sell his guitar equipment, I’d buy it from him, so he can’t get rid of it. I said to Janick “You’re going to do this song with me, so you can’t sell your equipment.” He said “What song?” and I said, “Well, let me figure that out over the weekend.”

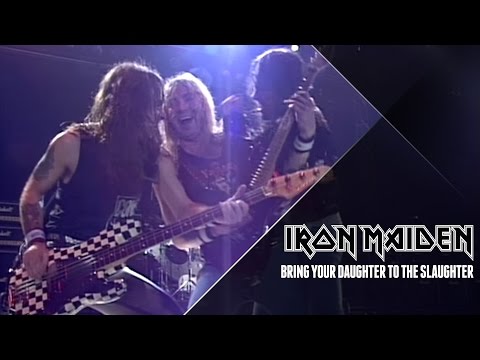

So, I’m at a friend’s house and he’s got an acoustic guitar. I said, “Hey, this is catchy” [singing] Bring your daughter to the slaughter / Let her go, let her go, let her go. He said. “Yeah, that’s kind of catchy,” I thought we’d have some big crash chords in the beginning then do a whole AC/DC ba, ba, ba, bang, and then we’d have a bunch of mad chanting monks in the middle. That’s it. Job done.

AS: And then it ended up on Maiden album [No Prayer for the Dying].

BD: So Janick came in and we rehearsed and recorded the tune. Then Steve [Harris] heard it and went ‘I love it. Let’s put it on a Maiden album.’ I had no intention … I mean, I had never seen A Nightmare on Elm Street film and I thought that maybe the words should have something to do with the film. I said, “Somebody tell me. I don’t want to watch all the damn things. What’s the story about?” Basically, young girls get cut up and abused by this old guy, but only when they’re asleep. I went, “Oh, well, that’s nice”—not. So I wrote some not-nice, abusive lyrics that I thought reflected what I thought the movie was about. Don’t try irony. It never works.

In the meantime, a guy from what was then CBS Records heard the song and [said] “I love that song,” and I said “Really?” He said “I want to sign you to do a solo record. Are there more songs like that?” I was like “Oh yeah, loads.” So I went back to Janick—and I also had a deal with EMI that allowed me one solo record as a member of Iron Maiden—so I was like “Shit I’ve got a worldwide release of a record that we haven’t written yet.” I went to Janick and said we have two weeks to write a record so we did all of it in two weeks. Then we had a like “Since You Been Gone” [Rainbow, 1979] with “Tattooed Millionaire” and that was catchy. The best song on the album was one that Janick actually wrote, “Born in ’58.” It’s the best song on the record by a country mile. It’s not derivative. It’s not tongue-in-cheek. It’s very well played, almost on the cusp of Spinal Tap.

AS: Then all eyes were on this album since it was your first outside of Maiden, but it wasn’t necessarily what you would have wanted to present as your debut.

BD: I was so gobsmacked that loads of people went out and they loved it, I guess in the same way people like The Darkness and stuff like that. Then I realized that people thought that it [‘Tattooed Millionaire’] was actually what I would be doing if I [made] a real solo record. We did it as a bit of a laugh. It was a bit of a joke, and everybody was taking it really seriously. I was like “Oh s–t, everybody thinks this is me.” It’s not.

AS: So by the time Balls to Picasso came out, was it clear what type of music you wanted to make as a solo artist?

BD: When I started working with Roy [Z] on Balls to Picasso, it was not the record it should have been. The reason was that neither myself nor Roy had known each other for long enough. It would have taken me turning to Shay Baby, the producer, and saying “Roy is going to do this.” But by this time, I was kind of shell-shocked, because I’d left Maiden unexpectedly—for them and for me—and I had no master plan. I thought, “Well, what do I do now? Well, I’m a musician. I write songs, and the last thing I did was Tattooed Millionaire.” Oh, f–k.

I had a bunch of material but I didn’t know where anything belonged anymore. I knew where everything belonged when I was with Iron Maiden. But out of Iron Maiden, I had no idea where I belonged, where music belonged, where the world was, or anything because I was out in the big wide world. I’m not in the Maiden protective bubble. And there is one, you know, and when you’re in it is brilliant. There’s lots of good things you can say about that, but for me, it was wanting to have my moment of creativity outside of that bubble.

I soon realized that it was a lot easier said than done. I had no idea how to work and create things outside of that Maiden bubble. So I ended up making three records, all of which were basically put on the shelf. The only one that came out was the third incarnation, Balls to Picasso.

AS: Everything eventually led you to The Mandrake Project, which you actually had in the works for more than a decade.

BD: Longer than that. I didn’t know I had it in the works because you don’t know what’s in the works until it drops out of your mouth. I’m a big believer in the way the subconscious is writing your story, and you don’t even know it. If you allow it to happen, then that’s the best way of all. You can try and make it happen, but that’s when people go “Oh yeah, it’s okay. It’s another, blah, blah, album. It’s another one of those albums. It’s good. It’s competent. It’s in tune. It’s all in time. It’s got exciting moments.” It’s like you’re damning it. And this is not one of those records. I’m just gonna come straight out. For me, I think this is the most extraordinary record I’ve ever made.

AS: Now, more than three decades into your solo career, what motivates you to write now?

BD: I think my motivation for writing songs has become more honest over the years—not in terms of stealing things from other artists or anything like that. I mean being true to yourself as opposed to writing in a style that you think people want to hear. Writing songs that you think people want to hear as opposed to writing songs that fulfill you and your purpose—whatever that purpose might be. Even if you don’t know what the purpose is, there is one in there somewhere.

Read more with Bruce Dickinson from the March/April 2024 issue of American Songwriter HERE.

Photo: Gareth Cattermole/Getty Images