The prophetic words of Radiohead’s Thom Yorke finally defined a generation of twenty-somehings burned by 60’s peace and love turned Reaganomics. “Where do we go from here, the words are coming out all weird. Where are you now, when I need you?” In ’93 the so-called Generation X was reeling from the loss of Seattle rock demigod Kurt Cobain and the commercialization of nouveu-hippie style. Flannel shirts, sandals, goatees, dreds and pierced body parts that once seemed anti-establishment had become fashion runway fodder.

The prophetic words of Radiohead’s Thom Yorke finally defined a generation of twenty-somehings burned by 60’s peace and love turned Reaganomics. “Where do we go from here, the words are coming out all weird. Where are you now, when I need you?” In ’93 the so-called Generation X was reeling from the loss of Seattle rock demigod Kurt Cobain and the commercialization of nouveu-hippie style. Flannel shirts, sandals, goatees, dreds and pierced body parts that once seemed anti-establishment had become fashion runway fodder.

Videos by American Songwriter

So again we stared longingly across the Atlantic to that little island from whence we came. With the United Kingdom and the U.S. it certainly seems there is “no place like home.” At first the new British invasion stuttered with the heavily Beatles-influence band, Oasis. It was commercially successful but lacked the voice that the kids were looking for. Thankfully Radiohead swooped in and made it clear with its landmark releases, The Bends and OK Computer that Britain could indeed find new musical directions beyond the Beatles and the Stones.

Yorke’s lyrics epitomized social dystopia and forged a new path beyond the faux-psychedelia of Oasis. Suddenly the irony and angst of grunge-rock was morphed into racor-sharp social commentary that attacked mass marketing superficiality by turning the camera on its operator. In Yorke’s uncomfortably haunting falsetto we discovered that it wasn’t just out parents fault for giving in to materialistic temptations but our own as well. On top of that we were programmed by television and technology to do it even more quickly and easily. Radiohead revealed the dangers of multi-media conglomerations in all things manufactured in the sublime “Fake Plastic Trees” and prophesized the deterioration of humanity itself on cuts like “Paranoid Android,” “Let Down” and “No Alarms No Surprises.” Catch phrases such as “kicking screaming Gucci little piggie” and “crushed like a bug in the ground” portray the despair of the ever-morphing cyber landscape that surrounds us and slowly chokes us out of our last breath of carbon monoxide.

True, this is not your mother’s Brit-pop. The Beatles were hopeful. They led us to believe that “all you need is love,” just to “let it be” and that we should all just “come together.” Well, I love th Beatles but I’ve learned the hard way that you ned case as well as love, war as well as peace, and “coming together” through technology can actually help to separate us from tactile human interaction, allowing us to build portico upon façade of our true identities.

The brilliance of Radiohead culminated in its release of last years’ “Hail to the Theif.” It’s lyrically their most focused effort to date. The group manages to attack political fascism while simultaneously taking the blame for checking out and cowering safely behind western civilization’s military superpower juggernaut. “I’ll stay home forever where 2+2 always makes 5,” wrote Yorke, “walk into the jaws of hell, we can wipe you out anytime.” Radiohead is the dark Beatles; just as important and revelatory to their respective generation.

On a somewhat lighter note is the British piano/guitar pop band Coldplay. In terms of financial success, it has surpassed Radiohead with its million-selling and Grammy-winning albums, Parachutes and Rush of Blood to the Head. Interestingly enough, when Coldplay released its first single (the achingly sublime “Yellow”) they were called “Radiohead lyte” or “bed-wetters” by the British press. Since then the world has been eating their skeptical tongues as Coldplay and lead singer Chris Martin (recently married to Gwyneth Paltrow) have achieved household TV-cable recognition status. There is no hidden political agenda with Coldplay. Martin is often seen wearing “make trade fair” slogans on his person, but most of his songs are just introspectively gorgeous gems that capture the deepest of human longings for understanding and acceptance. Coldplay does for relationships what the Rolling Stones did for sensuality. Martin’s prose is direct yet exploratory and ultimately a victory of substance over style.

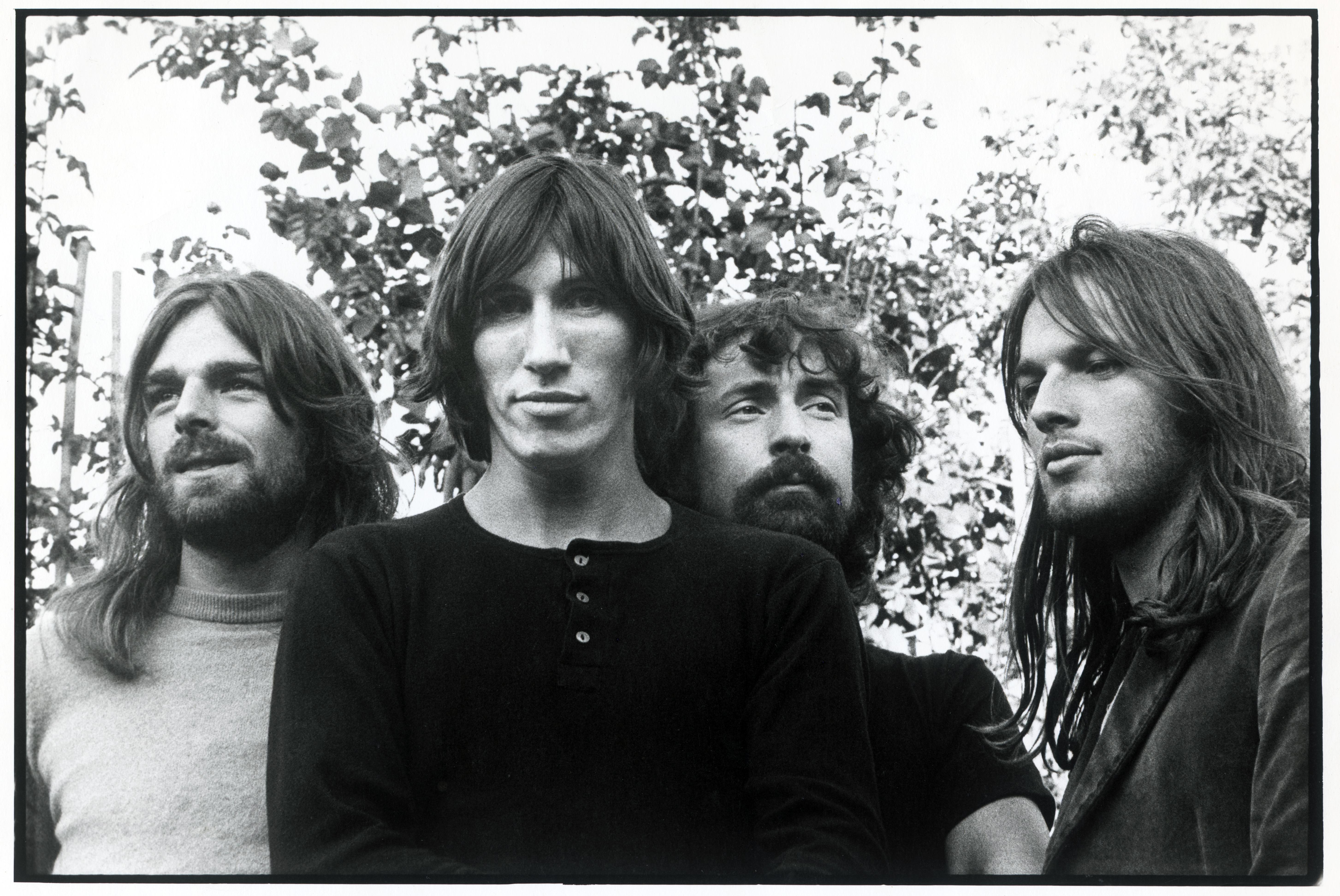

Both Radiohead and Coldplay owe a debt to rock bands but are influenced by another great British art-rock band, Pink Floyd. Like Floyd, the new British sounds is decidedly melancholic and symphonic without the guitar-hero posturing or David Gilmor. These new bands are the least “American” of all the British rock to date and a sobering twist in the saga that began by teaching our music back to us in the ‘60s and then ultimately redefining it in the 21st century by predating rock and roll itself. This is not to say post-modern Brit-pop doesn’t rock, it just does so at a deliberate pace that is primarily compositional.

The world finally has its next wave of great British bands that rival the Beatles and the Stones in influence, popularity and innovation. These bands have successfully outgrown the deictic shadow ‘60s of Lennon/McCartney and Jaggar/Richards by constructing a pharaoh-like pyramid all their own. The new Brit-pop influence is so far-reaching and vital that it has even influenced genres as remote as contemporary Christian, Americana and country. Wilco’s “Yankee Hotel Foxtrot” is decidedly Radiohead meets middle America. Grandaddy postulates on the aftermath of mutually assured destruction on “The Sophware Slump.” Whiskeytown’s “Pneumonia is filled with sparse production and controlled melancholy. Josh Rouse’s latest is rapt with spacious keyboards and quiet desperation. Christi Starling deftly employs the “Coldplay” guitar sound on “Water” and Keith Urban uses “Coldplay” harmony on his single, “Raining on Sunday.”

Leave it to the Brits to remind us again what is great about music: melody, simplicity, vitality, originality, and above all a need to communicate honestly. I hope we Americans can learn our lesson this time and not wait for the next British invasion to appreciate and continue to create the great music we’re capable of on this side of the Atlantic.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.