Videos by American Songwriter

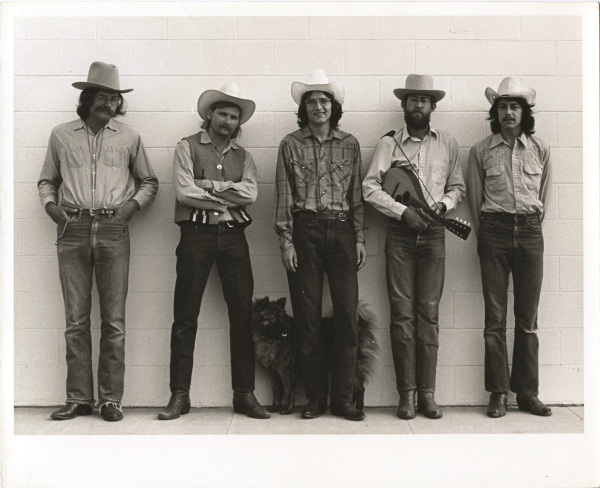

Since reconvening decades after never really breaking up, the Flatlanders have been perfectly happy doing occasional albums and tours. Though they’ve long carried the “more a legend than a band” tag, they’d moved well beyond its rather bizarre origins.

Which is why Butch Hancock, Joe Ely and Jimmy Dale Gilmore were shocked when they discovered their history had another chapter – with some unbelievable twists.

More than 30 years after they’d started jamming together in the house they shared in Lubbock, Texas, Ely, Hancock and Gilmore learned their very first recording still existed. Not only that, it was still in perfect shape and sounded terrific – despite sitting since 1972 in a Lubbock closet. And it contained four great songs – Gilmore’s “Number Sixteen” and “Story Of You” and Hancock’s “Shadow Of The Moon” and “I Think Too Much Of You” – they’d never re-recorded. Now, 40 years after doing the demos that should have launched their career, New West Records is releasing the extraordinary chronicle of the Flatlanders’ genesis as The Odessa Tapes, complete with an interview DVD and photo book.

As Ely and Hancock recall, they used to wake up each day, start playing and keep going – often till dawn. Their place became a musical hub; players constantly popped in to trade riffs, songs and tricks.

“It was a homemade music school that we were all partaking of,” says Hancock. “It took us all to another level.

But bassist Sylvester Rice wanted to get them an audition in Nashville, which required a demo tape. In January 1972, they traveled to Odessa to make one.

“We had no idea where we were. We recorded all through the night and all through the morning,” recalls Ely, whose high harmonies weave around Gilmore’s ethereal lead vocals. “At sunrise, we did 14 songs together and drove back to Lubbock.”

The tapes went to Plantation Records owner Shelby Singleton, who invited them to Nashville. They re-recorded much of that session, plus other tracks.

“They brought in some strings and did a pretty bizarre mix on it,” Hancock remembers. “It was really overproduced. We figured that if we’d been in California and done what we did, we might have had some success in the commercial world at that time. But I don’t think anybody in Nashville knew what in the world to do with us.”

Though Gilmore was already singing songs like the hippie-trippy “Bhagavan Decreed,” Singleton apparently had notions of turning Gilmore into a country star.

“That didn’t take,” Hancock says with a laugh, noting that, although Nashville didn’t get their blend of country, folk and rock influences, others did. “It was a thing that was just beginning to happen, the awakening of country music to the possibilities of other kinds of lyrics that were a little more involved than just fallin’ down drunk into your beer, and honky-tonk misery.”

After the Gilmore-penned “Dallas,” ironically now one of their most famous tunes, tanked as a single, Singleton met his contractual obligation by releasing a few eight-track copies of All American Music. Several years later, Ely told some British journalists about the album.

“They went to Nashville and found it,” he reports. The label, IRS/Stiff offshoot Charly Records, released it as One Road More, which sold well in Europe and got great reviews. The Flatlanders never saw a dime from it. “We had a kind of bitter love-hate thing,” Ely says. “We were glad that we had made [the album], but we felt no connection to it whatsoever.”

Ten years later, Rounder released it stateside as More A Legend Than A Band. The Flatlanders never collected from it, either. But it stirred enough interest to bring them back together, first to contribute “South Wind Of Summer” to 1998’s The Horse Whisperer soundtrack, then to record 2002’s Now Again. Then Lloyd Maines, a friend since those Lubbock days, informed Ely that Rice had the long-forgotten Odessa tapes. They were recorded on a then-state-of-the-art three-track reel-to-reel deck; turns out they’d lucked into an L.A.-quality studio built by Tommy Allsup. But the band had never heard the tapes and had no idea if they were even playable. Maines insisted they find out. Ely had to fly the tapes to L.A., where Capitol Records still has a few three-track players.

“They looked at ‘em under a magnifying glass and said, ‘Man, these are in perfect shape. Have they been stored in an air-free vault?’ I said ‘No, they’ve been in a closet in Lubbock, Texas.’”

They sound as if they could have been recorded yesterday. The audio is warm, the vibe is uncluttered and the songs have held up remarkably well.

“We were just amazed at the quality of it,” says Hancock, “and the presence – just literally like sitting around in the living room, like we used to do in Lubbock.”

As Ely notes, the saga makes “a pretty damned good story.”

You might even call it legendary.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.