Videos by American Songwriter

Creativity – the muse – is a bit of a troublemaker. If she likes you, you’re in heaven. If she doesn’t, you’re in hell. Every songwriter who has ever faced a blank page knows all about her capricious personality, but never loses interest in her. Sometimes, though, we should be careful of what we wish for – we may get it. Dancing with the muse can be a dance with the devil.

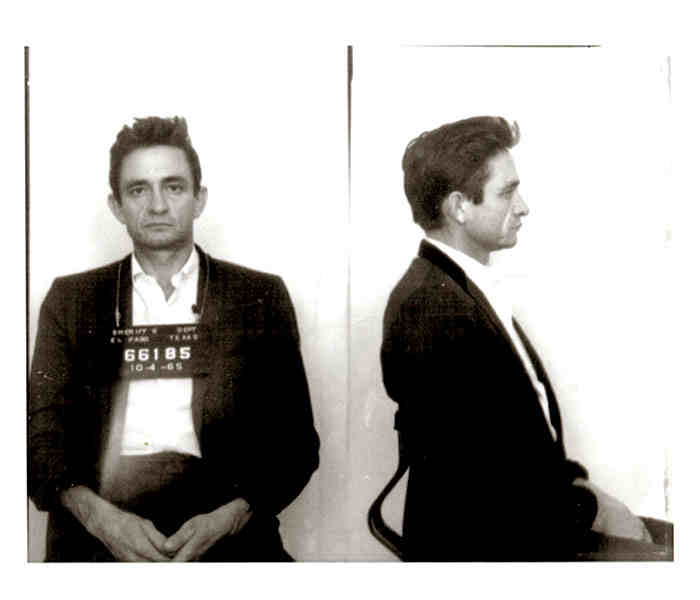

Consider Johnny Cash. In Walk the Line, the must-see 2005 biopic, we see how Cash (played by Joaquin Phoenix) struggled all his life against a host of inner demons inflicted by the tragic death of his beloved brother and the scorn of his stern, unforgiving father (Terminator 2‘s Robert Patrick). Like a lot of children victimized by circumstances beyond their control, Cash blamed himself, but his suffering and self-doubt only seemed to propel him deeper into his art – and tragically closer to self-destruction.

Childhood trauma and illness seem to figure prominently in the lives of many artists, and as adults, many pay the price. Ray Charles’s brother George drowned in a washtub while five-year-old Ray, hampered by failing eyesight, screamed for help, a tragedy that affected him his entire life. Two years later, Ray went completely blind. As an adult, he fought drug addiction. (See Jamie Foxx’s brilliant performance in the title role of the 2004 film Ray.)

When Hank Williams was only seven, his father, Lon, developed facial paralysis. Doctors attributed it to an aneurysm and committed him to a hospital for eight years, most of Hank’s childhood. Hank suffered from spina bifida, a birth defect that causes intense pain, which contributed to problems with alcohol and drugs. While his death at age 29 remains something of a mystery, a mixture of morphine (for pain) and alcohol seems to have played a role.

As a child, Mozart – who incidentally wrote over 100 songs and arias in addition to his famous symphonies and instrumental pieces – suffered from rheumatic fever, typhoid fever, pneumonia, and smallpox. His ambivalent relationship with his overbearing father is dramatized in the 1984 film Amadeus, starring Tom Hulce (another must-see movie), which shows this particular demon stalking the stage of Don Giovanni. Nutrition was unknown and health care was primitive in Mozart’s time. He may simply have worked his weakened body to death.

Most of us are aware of the story of John Lennon’s childhood through biographies and films such as Nowhere Boy (2009). Unquestionably John was drawn to music and art as a way of coping with the pain of his father’s desertion and the conflicts between his protective aunt and unreliable mother.

Elvis Presley was born in a shotgun shack in Tupelo, Mississippi, and was haunted by the death of his twin brother, Jesse, throughout his life. His early death was attributed to drugs, but was drug abuse strictly a cause, or more of a symptom?

Childhood sorrows may lead to brilliant artistry in other fields. Think of Van Gogh, who said, “My youth was gloomy and cold and sterile.” His demons caught up to him as an adult.

Bobby Fischer, whose unhappy childhood propelled him into chess at the age of six, said he wanted to write songs, and couldn’t understand why he was a failure at it. “Because you haven’t lived,” said his friend, grandmaster Larry Evans. Fischer’s obsession with chess left him socially backward. Ultimately he abandoned the chess world to wallow in paranoid delusions of radio waves in his fillings and a global Jewish conspiracy. He died unnecessarily of an illness he refused to treat, exiled from his native country by the same behavior that isolated him from the world.

Or consider the little boy who had a perfect childhood for an artist, including several serious childhood illnesses, an abusive, alcoholic father who beat him and ridiculed his desire to paint, and a protective mother who encouraged him to be an artist. The father died when the boy was only fourteen. Then his cherished mother died, too, leaving him an orphan at eighteen. At nineteen he went off to art school, where he promptly failed. Then, in the midst of defeat, he discovered his greatest asset, his voice, which led him to unimaginable success. Did he become a singer-songwriter? No, he became Adolph Hitler, and set about inflicting his inner demons on the rest of the world.

The moral of these stories? While we may envy certain things about an artist’s life, inner demons aren’t one of them. Their power to destroy has been proven over and over. If you’ve got’em, you have to learn to deal wisely with them. Learn where they are in the room, and avoid tripping over their taloned feet. If you’re lucky, they will help you make great art, and you’ll survive.

Abandoning self-pity seems to be a wise step, though often easier said than done. Scottish singer-songwriter Donovan grew up in a bombed-out, working class neighborhood of Glasgow and contracted polio at the age of four, which left him on the outside, looking in, a stance that is sometimes echoed in his songs. “I kind of look back on it and think it was positive for me because it made me withdraw from my pals and realize I was different,” he says.

One of my literature professors, Max Schott (author of Murphy’s Romance), once said, “There are two kinds of neurotics: Good neurotics blame themselves, bad neurotics blame others.” Artists are often good neurotics, which is why they must be on guard against destroying themselves. While some people suffer silently with their demons, artists make another decision – in a Freudian sense – to devote themselves to art with a passion because it’s the only thing that takes away the pain. For this reason, artistic genius often flourishes in the midst of great adversity, while individuals with advantages of birth and health and talent may be left far behind.

As Chick Corea says, “Successful artists have a quality of persistence that ignores setbacks, downfalls and difficulties… they just keep going, no matter what. The artist must reach people with his art, no matter how hard the existing environment works against him.”

And that goes for “her art,” too.

Theoretically Speaking

The previous blog post suggested “focused listening” as a way to understand the structuring force of rhythm in music. By now you should find it fairly easy to detect the beat, the measure, and the larger units of time, including two-measure sections and four-measure phrases.

But “music in” is vastly different from “music out.” In other words, creating music requires a completely different way of thinking from what you’ve been doing – performing or passively responding to music written by others.

Rhythm, plain and simple, is consistently the most underestimated feature of creative musicianship, so it might be easy to dismiss the exercises you’re about to read here as too easy or too drab. Yet there’s no doubt that among the professional and highly gifted musicians I have known, all had an extraordinarily keen sense of time. These exercises will help you awaken the same ability. I go into much more depth about this in my book (Compose Yourself, on Amazon). For now, however, I invite you to spend one week learning how to improvise the basic rhythmic units of time: measures, sections (two measures), phrases (four measures), and periods (eight measures). If you think it’s too easy, can you easily improvise an eight-measure rhythm and repeat it perfectly? The only student I’ve ever had who could do this with ease was a fifteen-year-old with about eight years’ experience at drumming.

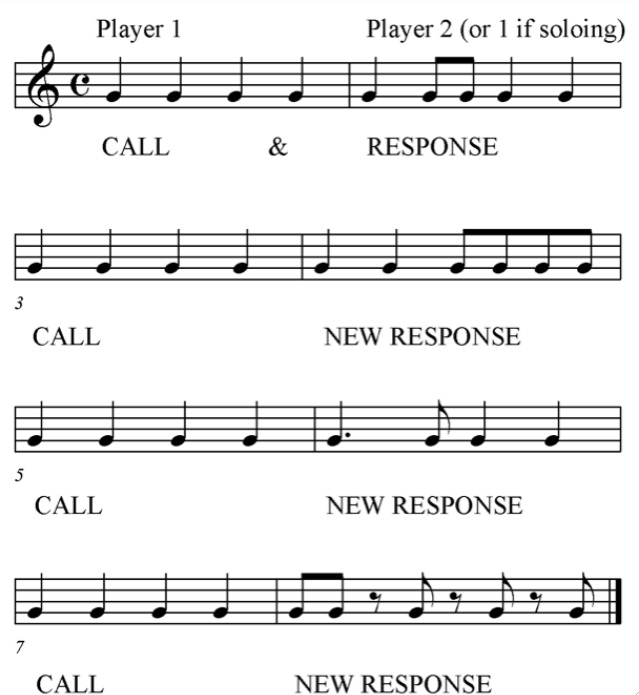

The exercise is based on a “call and response” concept. You hear a measure, you improvise a measure in response (clap, sing, play a guitar while muting the strings with the left hand). Try to improvise numerous responses to a single “call” measure:

Begin with one measure, using at least ten different “call” rhythms, then extend the call-and-response idea to a section: hear a two-measure rhythm, improvise a two-measure answer. And so on for phrases and periods. The game can be played solo, but it is best to play it with a partner, where it will resemble a dialog drill you might find in a foreign language class. Pure imitation (parroting) the call rhythm is a legitimate move – it just shouldn’t be overused.

This drill accomplishes a couple of important things. First, it raises your Rhythmic I.Q. (Imagination Quotient), which means it builds a rhythmic vocabulary. It also builds the abiity to think ahead in time – to cultivate an awareness of where you are in the measure, the section, the phrase. Second, it strengthens the foundation of the musical language. The reason most of us fail when we seek inspiration is that our musical minds are too underdeveloped to handle the three elements of music – rhythm, harmony, and melody – with clarity.

You undoubtedly have no trouble forming words in your mind before you speak them – we all do that. The rhythmic drills allow you to perfect the ability to do the same with rhythm. When you have done the same with harmony and melody and can juggle all of them at once, you are fluent in the musical language. You will know what you’re saying and know how to say it.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.