Videos by American Songwriter

(This column is featured in the March/April issue. Subscribe here. And get the latest, free e-Book here).

Break out the champagne – this issue marks a milestone, the first anniversary of “Measure For Measure.” So please, kick off your shoes and make yourself at home while I tune up the Martin; I have a song to sing. With a tip of the hat to ABBA, it’s called “I Have A Dream.” I’ve been singing it for six issues now, but since some folks are here for the first time, let me devote the first couple of verses to where we’ve been so far.

The first column (March/April, 2012) described the origins of “Measure For Measure” in my lessons with UC San Diego music professor and computer guru Jef Raskin, better known as creator of the Macintosh (Steve Jobs took over after Jef founded and led the project for a couple of years). Jef, a brilliant teacher, did for my understanding of music what the Mac did for computer users: He made composition easy.

Now my dream is to do the same for you, to make songwriting as easy and natural as breathing. Instead of going down the well-trodden path of music theory, I’ve been treating it like a language course, using dialog games involving words and music. First we covered rhythm (March/April), then harmony (May/June), then melody (July/August until now). Our goal is exceedingly modest: learn how to compose a catchy two-measure melody. If you can do that, you can write a song – a good song.

Why the accent on melody? Well, years ago, while arranging excerpts from over 2,000 hit songs for a software game, I realized that they generally had one thing in common: unity between lyrics and melody. In other words, the lyrics and melody underscored each other’s emotional content. When that happened, the effect was way out of proportion to either one of them alone. Together, they came to life, like matching strands of DNA.

But what’s the secret of this magic? Most of us are passably good with words, so the question boils down to melody. How does one compose a moving, memorable melody? Music theory can tell us a lot, but it can’t tell us that, so I consulted a higher authority.

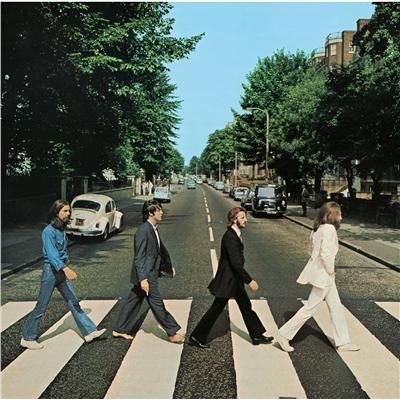

Using Hal Leonard’s The Beatles (Paperback Songs) as our textbook, I began to show how Lennon and McCartney expressed feelings through scale tones, intervals, and phrase forms. In e-books, I was able to amplify on these topics. (To get “Making Rainbows” and other e-books, e-mail info@americansongwriter.com and write “Measure for Measure e-Book Request” in the Subject line.)

In 2013, we turn to the all-important question, “What next?” That is, once you’ve got two measures that rock, how do you continue?

This is a problem that has stopped many a song in its tracks, but the answer is fairly straightforward: Whatever you do, it must relate to what you’ve done before. The song must grow organically. There are three ways it can do this: exact repetition, variation, or contrasting ideas.

The easiest path is to duplicate your melodic DNA, that is, repeat your phrase. Look at “All You Need Is Love,” (starting with “There’s nothing you can do that can’t be done”), “Baby, You’re A Rich Man,” “The Ballad Of John And Yoko,” “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “Eleanor Rigby,” or “I’m A Loser.” Sometimes you might change the harmony in the repeat, as in “For No One.”

Music thrives on repetition, so don’t hesitate to use it, but realize that by doing so you are stoking anticipation for a break in the pattern.

A powerful pattern-breaking technique used by all great composers is to repeat a phrase and change a couple of notes at the end. See “And I Love Her,” “Every Little Thing,” and “I Will,” among others. Try it yourself with four or five-note phrases.

The reason this technique is so powerful is that it can flip a “question” phrase into an “answer,” or cast a surprising emotional hue over an entire verse, as it does in “Across The Universe,” where the first phrase ends on A7 (on “Across The Universe”), and the second phrase ends unexpectedly on G minor (on “caressing me”). The effect is similar to rhyming in poetry. My next column will show how to use melodic rhyme to pluck the heartstrings.

Another way song-DNA can grow is by building parallel phrases on different scale tones, as in “Nowhere Man,” where phrase 1 begins on “Sol” (“He’s a”), phrase 2 begins on “Fa” (“sit-ting”), and phrase 3 begins on “Re” (“mak-ing”). All three phrases are very similar. Overall, they outline the scale steps “Sol-Fa-Mi-Re-Do,” which helps the melody tell a story. (For more on “Do-Re-Mi” see my e-book, “Singing Sol-fa.”)

In closing, be sure to check my blog at americansongwriter.com for a new e-book on how to grow a song. My New Year’s resolution for 2013 is to bring you more videos on the dialog games. Meantime, keep composing rainbows. For example, when you’re at the supermarket, use bits of overheard conversation as lyrics for rainbow phrases. The results will surprise you, but please, improvise them in your head – don’t burst into song in the frozen foods section. The uninitiated might not understand.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.