Videos by American Songwriter

The Quest for Creativity

If your name happens to be Bob Dylan or Tori Amos or John Mayer or Caetano Veloso, Dave Matthews or Jewel or Taylor Swift – please, skip this blog! Creativity is not a problem for you. If, on the other hand, you’re someone like me, someone who has flashes of inspiration now and then and would like to have more, then please read on. There might be something here to amuse you.

This is the first of my blog posts for American Songwriter, and in casting about for a theme, I settled upon creativity, because romancing the muse has been a preoccupation of mine as far back as I can remember. Creativity, or the pursuit of it, is why I’m sitting in a Starbucks, alone with my laptop, instead of working at a “real” job. But if you’re a songwriter or a musician or a gambler, you can probably empathize.

Measure for Measure, which will appear here on a regular basis, will pursue a broad range of topics, including the joys and sorrows of a musical career. But my main goal is to inspire you to write more and better songs, and to give you the tools to do so. The inspiration part will come from anecdotes, reviews, stories, opinion pieces, and interviews with artists. The tools part will come from tidbits of music theory. If music theory normally gives you a nosebleed, I think you’ll find “Theoretically Speaking” (see below) a refreshing change of pace.

As to my qualifications, that’s a long story. Stardom certainly isn’t one of them, but suffice it to say that my recently published book, Compose Yourself! – Songwriting and Creative Musicianship in Four Easy Lessons, generated enough interest at American Songwriter for them to invite me to contribute. I’m much obliged, and I hope that Measure for Measure will justify their confidence by keeping you entertained.

But back to creativity. For most of us it is a quest. It doesn’t come easy, or what comes easy to us is none too original. We run down the road with our creative arms flapping, trying to get airborne, but we run out of breath before we ever get off the ground. Even if we do finish something we start, we are haunted by the feeling that it could have been better. A lot better. And when our friends say, “That’s great,” well, we’re glad, but we’re seldom sure they aren’t just being nice, like the friends of a mother with a hopelessly ugly infant.

So what to do? Read books? An excellent idea. I have a lot of books on music and songwriting on my shelf. Some are quite good. Jimmy Webb’s Tunesmith – Inside the Art of Songwriting comes to mind (Hyperion, NY, NY, 1998), as well as the fascinating How Music Really Works! – The Essential Handbook for Songwriters, Performers, and Music Students (http://www.howmusicreallyworks.com), by Wayne Chase. There are other well-written, inspirational books by successful songwriters that focus on lyrics and business realities as well as music theory, such as Jason Blume’s Six Steps to Songwriting Success, Revised Edition: The Comprehensive Guide to Writing and Marketing Hit Songs. I will review these and other noteworthy books in future blogs. But in general, as good as these authors are – and they are all quite good – I can’t think of any book, no matter how enlightening, that made me want to run out and write a song after I put it down.

And it’s not their fault!

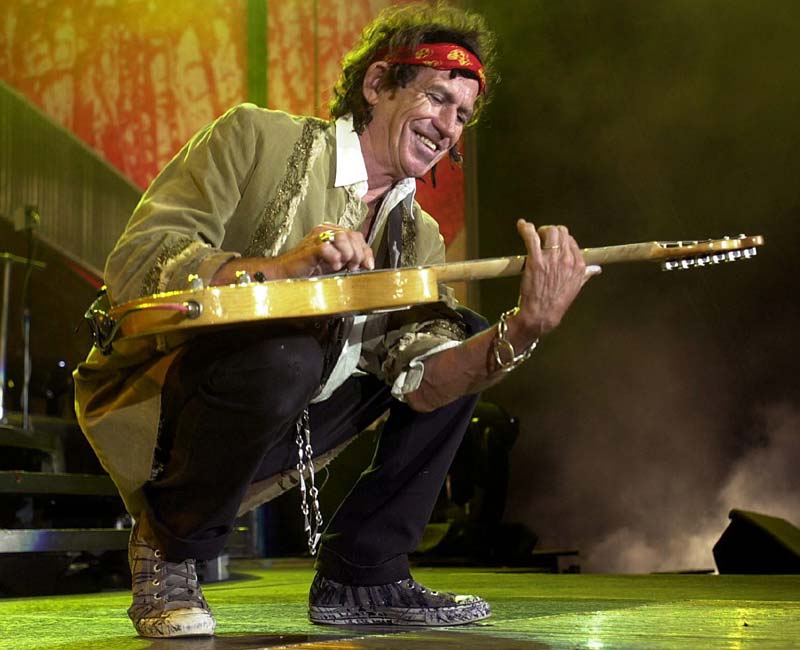

Just look at how good composers write songs: it seldom has anything to do with books, unless it’s a songbook. Keith Richards, for instance, says he gets out the Buddy Holly or Eddie Cochran songbook and plays around until something happens, adding, “I never sit down and say, ‘Time to write a song. Now I’m going to write.’ To me that would be fatal.” (From a 1992 interview with Guitar Player magazine.)

Talented songwriters don’t need to work at it, because anything can suggest a song to them. As Richards says, “Songs are running around – they’re all there, ready to grab.” Not only that, sometimes they grab you, like “Yesterday,” which came to Paul McCartney in a dream.

I don’t know about you, but I don’t have too many songs coming to me in dreams. Nor, despite decades of writing experience, can I sit down like Stephen King and write a novel without planning it out first. This exposes one of the problems with taking advice from gifted artists – they take certain capabilities for granted and have trouble imagining what it’s like not to have these capabilities.

Perfect pitch supplies an even more dramatic example. Perfect pitch is that much-envied ability to name random notes played on any instrument without hearing a reference pitch first. Even the pitch of squealing brakes or a squeaky door hinge is as clear as, say, the color red to someone with perfect pitch. Perfect pitch is rare, even in music conservatories. A friend of mine named Steve has it, though he’s a software engineer and has no interest in becoming a musician. Years ago I asked him about it, hoping he could say something that would switch on the “perfect pitch channel” inside my head.

“I think you’re trying too hard,” he said. “It’s so obvious.”

Obvious? Well, unfortunately it’s no more obvious to me today than it was years ago. In a way, famous songwriters remind me of Steve when they talk about how they do what they do. Sure it’s obvious – to them, but not to me. Nevertheless, I think that something Keith Richards said offers an invaluable insight into the wellsprings of musical creativity.

The key word is play. Keith said he got ideas for songs by playing around with other people’s music. As noted by Oliver Sacks, neurologist and author of Musicophilia, “I think one word which goes through any thoughts of creativity has to do with play and playfulness.” Among the musically talented, this is something I have observed time and time again: an ability to play around with musical ideas, string them out, and vary them in a playful – not methodical – way.

Well, if it’s so obvious, why don’t more of us get it? Is it because musical playfulness is like perfect pitch – either you’ve got it or you don’t? Not at all! We are all born with this ability. Try these two experiments: How many sentences can you make up with the words cat, door, and midnight? How many ways can you think of to tell someone that they look good today? More than one, I am sure.

Music, too, is a language – meaning communicated with structured sound – and all of us can learn to do the same thing with musical words that we do so easily with spoken words, namely manipulate them, vary them, and transform them. But in general that’s not how music is learned or taught. On the contrary, it is often taught in an abstract, rule-based way that unintentionally stifles playfulness and hinders creativity.

This is less true of pop music, where creativity and improvisation are part of the job description. You learn a hundred licks on your guitar and you start making up your own. Most of the better songwriters absorb new songs, words and music and style, like candy, and call upon that knowledge when they create new songs. But developing a vocabulary of licks or memorizing a few hundred songs is not enough, in and of itself. You could do all of that and still go nowhere.

Riddles such as these consumed me for a good thirty years, until I met someone who dreamed up a method for teaching musical composition that seamlessly combined discipline and playfulness. Like a lot of things he designed, it worked extremely well. One of those other things was the Macintosh – the computer, not the raincoat. But that, of course, is another story.

To be continued.

Theoretically Speaking – A Lesson in Focused Listening

One of the reasons that music is a difficult language to learn is that so much is going on at the same time. Rhythm, melody, and harmony all mingle in the moment, creating a dense world of sensation. For the listener, that’s part of the beauty of it, but for you, the creative musician, it can be a source of confusion. Focused listening is a way to achieve clarity amidst chaos by paying attention to just one feature of the music at a time. Clarity supports creativity when you imagine new music in the theater of your mind.

Take rhythm, for example. By rhythm we mean patterns of time created by pulses of sound, whether long or short, accented or unaccented. Almost all of us overestimate our mastery of rhythm because rhythm is so basic to our musical experience. But responding to rhythm and creating it are two very different things. A creative musician needs the ability to sense longer pulses of time, such as measures and phrases, and maintain an awareness of rhythmic past, present, and future all at the same time. This may sound like an exotic skill, but it is similar to what we do every day when we speak, forming the words of a sentence in our minds before they leave our mouths.

The following simple exercise in focused listening will elevate your rhythmic consciousness.

First, choose one or two three-minute pop songs and get ready to listen to each one several times over.

The first time you listen to one of the songs, just enjoy the beat while clapping your hands or tapping your feet. This is how most people experience music, by diving into the river of time and letting the beat carry them along.

The second time you listen, focus on the downbeat. The downbeat is a regular, recurring accent that defines groups of beats. Each group of beats is called a measure. The beats per measure is termed the meter. With few exceptions, every measure in a song will have the same number of beats. In pop music, this usually means four beats per measure, counted “One, two, three, four.” Rock music often features a backbeat, in which beats two and four in each measure are accented: “One, TWO, three, FOUR.” A backbeat almost automatically sets your body in motion, but if you concentrate, you can clearly hear the downbeat. Once you sense the grouping of beats (the beats per measure), start counting them out loud: “One, two, three, four,” for example. Keep clapping. Don’t be afraid to exaggerate the downbeat.

The third time you listen to the song, continue to count softly, but clap only once each measure, on the downbeat (the “One” count) only. You are now expressing measures, rather than beats. At this level, you will also begin to sense longer spans of time, such as two measures (a section) or four measures (a phrase). Strictly speaking, a phrase may include more or less than four measures, but this depends on harmony and melody, which we haven’t discussed yet.

In pop songs, the two-measure section is one of the most important structural units. Literally thousands of songs use it, but for a good example, listen to “Love Minus Zero/No Limit” by Bob Dylan (from the Bringing It All Back Home album). We will have more to say about sections later, but for now, try to identify them in the songs you have chosen. If you can read music, a score will help.

Listen to the song for a fourth and final time. Start grouping downbeats into sections and phrases. By now you have heard the song enough times to imagine the way each section will sound before you hear it. Most people listen to a song beat-by-beat, only dimly aware of measures, sections, and phrases. Composers and improvisers think in larger units of time, and can hear relationships between them across even longer spans of time. Thanks to this exercise in hearing measures by isolating the downbeat, and then grouping measures together to hear sections and phrases, you are beginning to enjoy a composer’s-eye view of your favorite songs.

In future blog posts, we will learn how to hear and create harmony and melody across the three dimensions of time: past, present, and future.

Biographical Notes:

David Alzofon grew up in the musically-rich San Francisco Bay Area during the 1960s, in the neighborhood immortalized in Tom Wolfe’s Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. He started playing trumpet in grammar school, but got hooked on the guitar in high school at the age of 13.

In 1972, he graduated from the College of Creative Studies, UC Santa Barbara, in Fine Art, and immediately returned to school to study music. In the mid- to late-‘70s he began to study jazz guitar and assisted Musicians Institute founder Howard Roberts with HR’s popular jazz improvisation column in Guitar Player Magazine.

In 1981, his first book, Mastering Guitar, was published by Simon & Schuster. Shortly afterward, he became a full-time editor for Guitar Player, where his duties included editing multiple instruction columns and writing book reviews and album notes.

In the mid-1980s, he became User Documentation Manager at Information Appliance, a small start-up company founded by Jef Raskin, creator of the Macintosh. Jef, who had been a music professor at UC San Diego before coming to the Bay Area, eventually provided the composition lessons that formed the basis of Mr. Alzofon’s second book, Compose Yourself!, which was published in January, 2011.

Among other projects in Silicon Valley, he has written electronic novels and over 11,000 capsule movie reviews. Over a two-year period, he researched and arranged the most memorable parts of over 2,000 hit songs for a software game resembling Name That Tune, an effort that contributed to ideas contained in Compose Yourself.

Email the author at composeyourself@live.com

f

f

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.