“It don’t mean a thing (if it ain’t got that swing).”

Videos by American Songwriter

– Duke Ellington

Rhythmic I.Q. – your Rhythmic Imagination Quotient – What is it? What’s it good for?

As I write, the Songwriting ABCs channel on YouTube has fourteen videos, with a fifteenth to be added soon. All of these videos are tied to Excerpt 1 from Compose Yourself (my book), which is being serialized here in its entirety. (To get a PDF of Excerpt 1 – free, of course – simply email info@americansongwriter.com and write “Request Compose Yourself Excerpt 1” in the Subject line.) Incidentally, I will be releasing Excerpt 2 early, so you can read it while we’re playing the dialog games for Excerpt 1.

The videos for Excerpt 1 (and future excerpts) will follow this plan:

- First, everyone will be brought up to speed on the sight-reading skills needed to play through the examples. We’ve just finished this phase for Excerpt 1. (This is like a separate course within a course; if you’ve been putting off learning how to read notes, this will be a relatively pain-free introduction.)

- Second, we read and play through all the examples. This is what we’re doing now.

- Third, we play dialog games with the material in the lesson.

This may not be the fastest way to work through the book, but I’ve vowed that no student shall be left behind, so if you already know how to sight-read, please be patient. If you have questions about something in the book or in the videos, please feel free to email them to composeyourself@live.com.

The challenging material begins with the dialog games, which resemble the dialog drills we play in a language class. Through them, we will build the skills that lead to fluency in the musical language, or more than that, the songwriting language, which interweaves the poetry of words and music. Learn this language well, and you will become a conjurer, a creator of that magical experience that can come only through hearing a good song.

Now we all know a great song can move us to tears or laughter and remain in our hearts forever. So it always seemed jarringly weird to me that music was the only language that was taught as if it was devoid of meaning. Sure, the performances were emotionally moving, but what they taught us in school was like mathematics or chemistry. No one could decode the musical dictionary for me. What’s more, no one was even trying, no one, that is, except Deryck Cooke. In his not-so-easy-to-read book, The Language of Music (1959), BBC music critic and composer Cooke dared to decode the emotional memes of intervals, melody, and other musical elements. As a reward for his efforts, he was lambasted by critics.

However, I think his critics, and to a certain extent Deryck Cooke himself, missed the point. The point is not to write, or even attempt to write, a universal dictionary of musical meaning that everyone can then refer to for a precise definition of, say, the emotional value of a perfect 5th or a shuffle rhythm. Instead, as aspiring artists, we should write our own dictionary of musical meaning, which we can then apply intuitively to writing songs. We do this by meditating deeply on our response to intervals, scale tones, and other musical elements as they appear in songs.

Unless this dictionary-writing step is taken, how are we going to feel our own songs into existence, especially if we’ve been a victim of the intellectual approach to musicianship, which many successful artists scorn so thoroughly that they point with pride to the fact that they cannot read a single note?

It may seem as if I’m veering off-topic, so let me steer the discussion back to developing your Rhythmic I.Q. – what it means, why you should care.

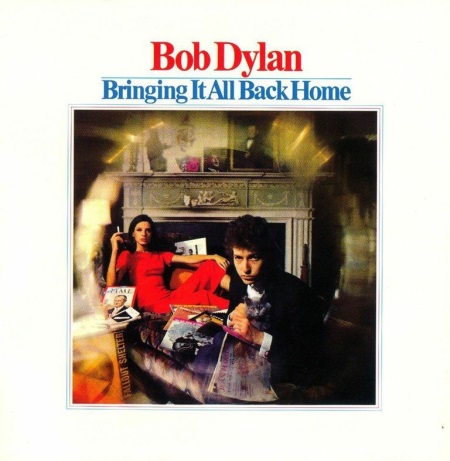

Lesson 1 is all about taking this all-important dictionary-writing step with rhythm. Time is the shaper of form in music (and songwriting). The forms of time – rhythm, in other words – are the scaffolding on which we hang the swinging lines of melody and skipping reels of rhyme (as Bob Dylan aptly put it in Mr. Tambourine Man). If your time sense is weak, you will have trouble juggling the other elements of music as they come online in future lessons.

Through the dialog games in Lesson 1, you will acquire a rhythmic vocabulary that will allow you to sketch out measures of music ahead of time in the theater of your imagination and place them in the larger framework of motives, sections, phrases, and periods that make up song form, with an awareness of melodic rhymes and resonances spread far apart in time. A higher Rhythmic I.Q. is essential for this.

This month’s blog is a kind of pep talk for all of my readers just before we plunge into the dialog games. I want to encourage everyone to get involved, even if you think the games are too easy or not close enough to writing actual music. All too often, we tend to overestimate our Rhythmic I.Q., which is natural since we’ve been tapping our feet, clapping our hands, and nodding our heads to the beat all of our lives. What could be easier? But music in is not the same as music out, as you will soon find out. While we all differ in our natural Rhythmic I.Q., in general it takes a lot of training to bring our natural abilities up to the level of a professional songwriter. The good news is that training conquers all. Even someone who has a low Rhythmic I.Q. can build a high one over time, as long as they are willing to train. And if you haven’t had this kind of training before, say by playing in a band, you will experience instant improvement across the board in your musical skills.

To sum up: Would you like to swing on a star? Carry moonbeams home in a jar? If we want to be better off than we are in a songwriting sense, then we must needs write our own dictionary of musical meaning. Only you can write that dictionary, so be here when the games begin.

Previously: Compose Yourself – On The Road

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.