Videos by American Songwriter

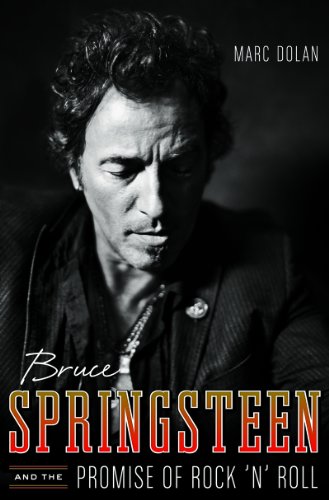

The excellent new book Bruce Springsteen and the Promise of Rock ‘n’ Roll examines the heartland rocker’s iconic discography in rich detail, while providing interesting biographical details along the way. In this exclusive excerpt (featuring two passages from chapter 9), author Marc Dolan writes about how the birth of Springsteen’s first child would inspire his early 90’s output and reinvigorate his career.

In April, as the arrival of their child drew nearer, Bruce and Patti moved from Hollywood to Beverly Hills, to a half-acre home on Tower Drive with a separate home studio but no pool. Bruce had been recording with Bittan, Porcaro, and Jackson for months now, but in so desultory a fashion that they had laid down tracks in at least three different LA studios. Bruce still liked to record through the middle of the night, but the days of block-booking weeks of studio time appeared to be over. When he had something from his home studio that sounded promising, he’d call up the musicians and see what space was available. If Randy Jackson wasn’t on hand when the time came to record “Leavin’ Train,” Bob Glaub from the “Viva Las Vegas” combo could fill in on bass. If Jeff Porcaro wasn’t on hand when the time came to record “Seven Angels,” Shawn Pelton could fill in on drums. Some of those participating in the sessions weren’t even sure whether they were contributing to Bruce’s ninth studio album or Patti’s first. Still, by June, Springsteen had at least nineteen tracks recorded for his project, more than enough for two sides of an album and a handful of B-sides. He would also have his usual leftovers (maybe quieter songs like “With Ev’ry Wish,” “Sad Eyes,” and “I Wish I Were Blind”) that might point the way toward a second, more countryish album that he could quickly pull together as a follow-up to the big soul-with-guitars release.

As usual, though, Springsteen appeared to have no intention of assembling an album on anybody’s schedule but his own. Besides, come June, he had more important things than music on his mind: it was time for Scialfa and him to prepare for the arrival of their son. When the contractions started, Springsteen figured the situation would get tense, he recalled later that year, so I [thought] it was kinda my responsibility to lighten things up. In late July, a few days after Patti’s birthday, he stopped in a drugstore to look for some silly novelty item that might break the tension during the delivery. He settled on a jokebook called How to Be an Italian, thinking, “Gee, when it gets really tight, I’ll crack out some Italian jokes.”

When the time came, though, he didn’t, and Scialfa was probably grateful for that. Around 5 a.m. on Wednesday, 25 July 1990, Evan James Springsteen was born. In anticipation of the event, Sting, ever the former English teacher, had given his recent friend a copy of Dylan Thomas’s Under Milk Wood as a gift, and after the boy’s birth, he incorrectly assumed that Bruce and Patti had taken their son’s name from a character in that work (an undertaker, actually, called Evans the Death). The truth, however, was that the name was yet another of the many fruits of Springsteen’s year of intensive psychotherapy. One therapist had encouraged him to get rid of the “ego validators and nuts” of old, and the initials of that jargony slogan apparently yielded his son’s first name.

New age self-help slogans aside, Evan’s birth was a watershed event for Springsteen. If a true connection with Patti had come slowly and with effort, what he felt when he first met Evan was something sudden and extraordinary. In describing the event, he always recalls it as “night,” their firstborn arriving in the hour just before a midsummer dawn. In talking about what he felt at that moment with an interviewer a few years later, he instinctively compared it to the thrill of live performance, the feeling that he had previously thought was the greatest he could ever know. “I’ve played onstage for hundreds of thousands of people,” he said, “and I’ve felt my own spirit really rise some nights. But when [Evan] came out, I had this feeling of a kind of love that I hadn’t experienced before.” And that feeling also scared him, he knew. It made him “afraid to be that in love.” I stood down there looking at him, he told an audience a few months after Evan’s birth, and it was amazing because I seen the first time he cried, and I caught his first tear on the tip of my finger.

From Evan’s birth on, live performance would never again be the addictive escape for Springsteen that it had been up to that point. Western society raises girls to be mothers far more than it raises boys to be fathers, but for some men becoming a father turns out to be the greatest adventure of their lives. In spite of, maybe because of, all the dark things he had written about the relationships between fathers and sons, Bruce Springsteen greeted the arrival of his own moment of fatherhood with a zeal he hadn’t exhibited since he first saw the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show. The greatest advantage that his considerable wealth could bring him that year was the fact that he didn’t have to work, at anything. He could spend the time with his spouse and newborn child that so many other, less well-off parents wished they could.

From June to December the only recordings Bruce made were two children’s songs, and in all of 1990 there were just two drop-in performances, both before Evan was born. After Evan’s birth, maybe the only two performers who could have gotten Springsteen out of the house and up on a stage, particularly by himself, were Jackson Browne and Bonnie Raitt, both of whom had been not just colleagues but friends for almost twenty years. The benefit at which they wanted him to perform was for the Christic Institute, a DC-based public-interest law firm that had taken the lead in publicizing the Reagan administration’s continued covert assistance to the Contras in Nicaragua, among other alternative issues. When it was announced that Springsteen would be topping the bill for a mid-November benefit for the institute, giving his first scheduled performances in over two years, the six thousand seats in the Shrine Auditorium sold out in forty minutes, as did the inevitable second show when it was announced.

In terms of Springsteen’s career, the Christic Institute benefits weren’t just his first scheduled concerts since the end of the Human Rights Now! tour. They were also the first concerts he had performed solo in at least eighteen years. Between the time he had spent away from performing and the ways in which he was trying to wean himself off so many unhealthy attitudes associated with his stage persona, Springsteen took the stage for the first concert on 16 November nervous, even exposed. It sounds a little funny, he told the audience before he started off the set with an acoustic rendition of “Brilliant Disguise,” but it’s been awhile since I did this so if you’re moved to clap along, please don’t. It’s gonna mix me up. Before he started “Darkness on the Edge of Town,” the next number, he reiterated, I’d appreciate if during the songs I’d get just a little bit of quiet so I can concentrate. That night, much of his between-songs patter consisted of similar apologies: for bad notes in a slow version of “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out” and for forgotten lyrics in, of all songs, “Thunder Road.” After “Mansion on the Hill,” one enthusiastic fan shouted, “We love you Bruce,” and the newly self-conscious performer immediately replied, But you don’t know me. On the page, such statements might sound petulant, but when you listen to recordings of the event there is a vulnerability in Springsteen’s voice that simply wasn’t present in earlier performances, not even when he was telling the Freehold story before “Spare Parts” at the beginning of the Tunnel of Love tour.

Of the songs Springsteen performed at the first Christic concert, a third were from Nebraska, which made sense given the solo nature of the performance. There was nothing from The River, his ultimate band album, two songs from Born to Run, and one each from Wild and Innocent, Darkness, Born in the U.S.A., and Tunnel of Love. Most interesting of all was the fact that he premiered four new songs that night, three of which he hadn’t even recorded yet. These three songs (“57 Channels and Nothin’ On,” “Red Headed Woman,” and “When the Lights Go Out”), which he had apparently written since Evan’s birth, had one theme in common: sex. The latter two were also among his most sexually explicit songs, making what are almost the first uncoded references in Springsteen’s work to female genitalia. It doesn’t seem like too much of a stretch to conclude that, since the birth of his child, Springsteen was enjoying not only the newness of fatherhood but also the resumption of conjugal relations with Scialfa. The next night he played a slightly different set, including the premieres of the more metaphorically inclined “Soul Driver” as well as “The Wish,” the song he had written about his mother nearly four years before. He may have been nervous, even a little off, but on the whole the two Christic shows were extraordinary, his finest and most spontaneous performances in years, and a powerful argument that he should have stuck to his guns and just toured for Tunnel of Love solo.

In December, he resumed recording, laying down studio versions of “57 Channels” and “When the Lights Go Out” (but probably not “Red Headed Woman”), as well as two newer, less impressive songs called “My Lover Man” and “Over the Rise.” By early 1991, he had laid down about two dozen tracks in a little over a year, certainly more than enough for an album. He could have released an all-neo-soul album, for example, or an album (to keep thinking in predigital terms) that gave the listener one soul side and one paranoid rockabilly side. Still, he continued to sit on the project. The album wasn’t finished yet.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.