Videos by American Songwriter

Randy Newman

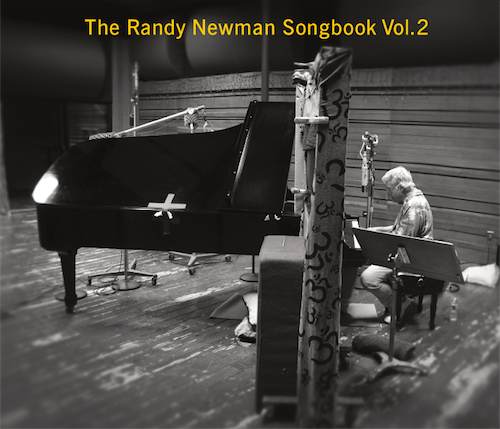

The Randy Newman Songbook, Vol. 2

(Nonesuch)

[Rating: 4.5 stars]

Randy Newman was talking about the relationship between his film music, for which he has won two Oscars and 18 nominations, and his songwriting.

“My father, who was not a musician, worshiped his brothers who did (film scoring),” he recalled in a recent NPR interview. “He thought it was the great art form of the century. He kept asking me, no matter what kind of acclaim I got early on for my songs and records, ‘When are you gonna do a picture?’ It was like that was the pinnacle of music.”

Newman had the unique advantage of growing up on Hollywood sound stages where his celebrated uncles – Alfred, Lionel and Emil – wrote and/or conducted the scores to dozens of films. He could have easily gone into the family business. But at first he resisted, preferring to become a professional songwriter at the age of 17, then an unlikely singer/songwriter.

Lucky for us. You can hardly make a better case that songs can be the equal of any art form than the classics on display in The Randy Newman Songbook Vol. 2. The album is essential listening for those who care about American music (not just the popular variety). For younger listeners who might as yet be unfamiliar with his pre-Toy Story repertoire, these tracks might be a revelation.

In the late 1960s world of confessional, mostly guitar-strumming singer-songwriters, Newman always stood apart: for his symphonic vision, backed up with superb arranging chops, as well as for the literary ambitions of his lyrics, mostly written from the point of view of unreliable narrators, sometimes tragic, more often ironic and mordantly funny.

Then there was his choice of subjects. As Newman points out, “90 percent of the world’s song repertory is love songs – but not with me. Not the wisest commercial choice I might have made,” he concedes. “But that’s what I was interested in.” Those interests included mindless racism (see “Yellow Man”), narcissism (“My Life is Good”), misogyny (“The Girls in My Life, Part 1” and others), political corruption (“Kingfish”) poverty and despair (“Baltimore,” “Sandman’s Coming”.) He remains the closest thing songwriting has had to a Dickens or a Twain.

His composing and his piano style have antecedents as fundamental to American music as Stephen Foster, Aaron Copland, and the entire New Orleans tradition from Scott Joplin to Fats Domino to Dr. John – yet he has long since established a style that is instantly recognizable as his own.

For the new disc, the second in a series of new piano/voice recordings of some of his finest work, Newman and long-time producers Mitchell Froom and Lenny Waronker selected songs from throughout his career, dating back to his eponymous first album in 1968 through 2008’s Harps and Angels, his most recent collection of new work.

Over the last 43 years he has been strikingly consistent in his quality and approach. From his first release, he seemed to emerge with his writing and arranging talent fully formed (the singing was…well, let’s just say he hadn’t quite found his voice yet). It included songs that are still considered some of the best of his career; for example, “Cowboy” (which made this edition of his Songbook), “Davy the Fat Boy” (which didn’t) and “I Think It’s Going to Rain Today” (on Songbook, Vol. 1).

Given his usual preference for writing himself out of the song, the album opener, “Dixie Flyer,” is an anomaly – one of the few songs in which Newman has said he consciously strove to use material from his own life. “I was born right here, November ’43,” it begins, and so he was, in L.A., to a mother who, faced with raising a child alone while her husband was serving in World War II, moved back to her home town of New Orleans, where Newman spent his early years. The song, one of his most poignant, describes the fish-out-of-water feeling of a Jewish family in the decidedly Christian Southland. That New Orleans lethargic drawl and syncopation had a profound, lasting influence on his musical soul.

More typical of his songwriting is “Suzanne,” which begins, unforgettably, with the lines, “I saw your name, baby/In a telephone booth/It told all about you, mama/Boy, I hope it was the truth.” (The perfect rhyme never announces itself; it just is.) If Sting’s subsequent “Every Breath You Take” contained intimations of obsession and menace, Newman’s song was explicit and uncompromising in its chilling depiction of a stalker and would-be rapist. Newman’s occasional love songs tend to be devastating, deeply felt portrayals of loss, regret and loneliness, exemplified here with 2008’s “Losing You.”

In both volumes of The Randy Newman Songbook, the pared-down arrangements, just voice and piano, thrust the songs themselves starkly into the spotlight. A word about his piano playing: the arrangements are meticulous, often microcosms of the original orchestral or R&B arrangements. Yes, there are differences, but the salient details, the dissonances, suspensions and resolves, are fully present and elegantly rendered. One of the finest examples of this on the album is “Sandman’s Coming.” Though little heard (it was originally written for ABC Television’s ill-fated 1990 musical drama series Cop Rock and was subsequently re-purposed for Randy Newman’s Faust), it remains one of his finest, most haunting compositions.

The strength and sometimes even the gruff beauty of Newman’s singing may surprise some listeners who have heard him only in one of his occasional TV appearances. Although his songs have been covered over the years by dozens of artists from Joe Cocker and Tom Jones to Judy Collins and Linda Ronstadt, as a performer of his own material nobody can come close to the way he fully inhabits his diverse cast of characters.

Perhaps the only fault one can find with the album is that it’s a retrospective. It makes us all the more hungry for his next album of original material.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.