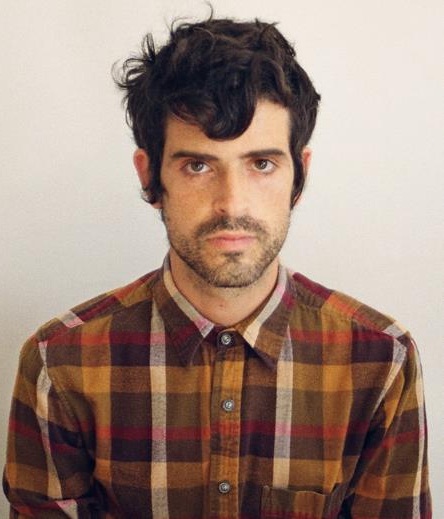

Devendra Banhart released his tenth studio album, Ma, on September 13. With a wide range of emotions layered over ornate and tasteful instrumentation, the record is one of Banhart’s most introspective and moving works to date. We talked with the Venezualan American musician about the new record, his activism and how he embraces being called a freak-folk artist despite thinking that it’s the “stupidest label ever.”

Videos by American Songwriter

This record seems to mark a step in a more introspective and personal direction—did you set out with the intention of writing a record like this, or did the songs just start coming out that way?

A bit of both. You start to write about your environment, and my environment was a very intimate, personal and maternal one. I realized everyone that is part of my chosen family I’ve known since they were kids. They’re all having kids. So, I’m kinda becoming this “auntie” that I’ve always wanted to be, showing little kids how to skateboard. That environment becomes information, which becomes the fodder for songs.

At the same time I’m finding myself in this position where I’m a new old person. I still listen to certain musicians for consolation, I still listen to certain musicians to augment a beautiful moment and I still listen to certain musicians to get me through a difficult one. That realization led me to start writing songs for songs, and on this record there are songs for songs. I reference Carole King as somebody who I really turn to and listen to. So, these themes kinda evolved and sprang up from the environment that I’m in.

The record began in Kyoto, Japan in a temple. That’s a particular environment, and that environment is something we wanted to recreate when we got home. I suppose the record might be just a product of its environment.

Did you notice a change in your songwriting style?

I think so. I noticed that there weren’t any characters. I wasn’t really writing as somebody else, which is something I always do. Every record there’s about three or four character songs, but on this record it’s just me talking to something that doesn’t really exist. It’s me singing to all the kids around me in my life, kinda imagining if I had a child. And if I don’t have a kid, maybe this record is everything I would like to say to my child. Maybe it’s everything I wish my parents had said to me. They were great parents, but certain things you want to hear. Some of these songs, like “Taking a Page,” I’m really just introducing my point-of-view to this imaginary child. So yeah, the songwriting is different, there aren’t any characters.

What designated the orchestration and the production was the environment. We recorded it in a house in Northern California surrounded by the Pacific ocean, and that definitely affects the way you write a song. It’s not really a city album. If I had been in some cosmopolitan city writing this record I think there’d be a lot more character songs, because you’re just observing other people. It’s like a “let me tell you this thing I saw today in the city” kind of songwriting style. This record was much more introspective because there’s not much to see other than yourself. That’s what being in nature does, it becomes a beautiful mirror. But it doesn’t necessarily mean that what you see is beautiful—most of the time it’s horrifying.

In a way, was it scary to write a record like this?

Well, fear is a good guide. What’s something you really don’t want to be singing about? Okay, that’s probably what you should be singing about. The best thing for us is usually the last thing we want to do. When it comes to the subject; what’s the most honest thing? What’s the most real thing? What’s really happening? How can you write about that in a way that’s honest and feels naked, but at the same time isn’t shoving something down someone’s throat or is totally annoying? It’s very difficult. You can’t really choose to not be annoying. There are songs that annoy you, but the person who wrote it didn’t go out to do something annoying. Hopefully you try not to annoy yourself too bad… but I fail every time.

When “Taking a Page” came out, you were quoted talking about how the night Trump was elected affected you—did you feel a certain urgency after that night to write music that was a bit more politically conscious? Does the current geo-political situation affect your writing?

Once Trump was elected it politicized everyone. There’s this chain of global radicalism that emerged. You suddenly get these really crazy racist people being elected, and waves of insanity. That politicized everybody.

The situation in Venezuela… it’s been getting bad for over twenty years, but I didn’t think it could get any worse. And it did, and it is at this moment. It’s in a gridlock, nothing really changing. It’s like the whole country is being waterboarded right now. There’s no relief. Those are things that are happening just like these kids being born, so I wrote this record where much of the theme is this opportunity to be around family members who are having kids and observe this relationship between parent and child. That becomes part of the record, and so does the political landscape. Everything became political because it became human. It’s not just politics, which so often can become a game of chess. It really became about human beings suffering. Suddenly Nazis are driving cars into rallies. It’s a very frightening thing, and it’s a human thing, not a political thing.

You’ve been involved in a lot of activism recently, working to promote and support the I Love Venezuela foundation, the Trans Lifeline and World Central Kitchen—what do you think of the relationship between entertainment and activism?

Well, it used to be that it was very important to remind artists to be philanthropic. I think everyone felt they’d need to write a protest song, though not everybody can. But everybody can express some concern for some kind of suffering on the planet. That was something artists and celebrities really needed to do back in the day, because they were the ones with the biggest reach.

That’s why people wrote things like “We Are the World,” which is my favorite footage of Bob Dylan… it doesn’t get old. I can watch it over and over again. It’s such a source of joy. I want to project that constantly in my house. He’s kind of there, kind of bored, but there—it’s just fascinating. He’s like the Mona Lisa. What happened that led to that expression?

But, there’s a responsibility of the artist or the famous person with a platform. That’s important and that continues to this day. What changed is that everybody has the opportunity now to try to relieve the suffering of whatever it is that’s important to them. Who cares if you’re an artist or if you’re a celebrity or if you’re famous or not? It doesn’t matter, you can still contribute $1 to something that matters to you. Maybe that’s ecological degradation, maybe that’s human trafficking, maybe it’s helping out an orphanage. Whatevers important to you, you can contribute a buck, just try to help out.

It was great to hear Cate Le Bon and Vashti Bunyan on the record. How did they get involved in the project?

By being annoyed. I annoyed them so much. It was really in order for them to stop getting emails from me.

Cate is really one of the greatest artists and a dear friend. I don’t know how she managed to be on this record because she recorded it while she was on tour which is impossible to do. Imagine not sleeping and not getting water and then playing for what feels like a thousand years, that’s kinda the reality of tour. Because she’s so amazing, she managed to get into a studio and track some vocals for the album, which is incredible.

Vashti is an old friend, and I think the archetype of this maternal wisdom. She’s an artist whose music I’ve been turning to for over twenty years, so I asked her if she’d sing on this record. She sings on the last song, which is a question, and the first song is a question. That seemed important to me to bring home the theme of the record by having Vashti on it.

Did you write “Will I See You Tonight?” with Bunyan in mind?

Yeah, absolutely. It’s kind of a duel duet, because I’m not really singing to Vashti, we’re both singing out our longing together. I like the idea of doing a duet that’s two people wanting the same thing. It’s not like “On My Own” where Patti LaBelle and Michael McDonald are talking about their divorce and how they’re on their own… actually, no, it is a little bit like that because they’re not really singing to each other. They’re both thinking about that relationship, it’s their own versions of it. So, it’s kind of like that. Yeah, I wanted to do a Patti LaBelle and Michael Mcdonald thing.

The press has been speculating influences from Leonard Cohen, Harry Nilsson, Donovan, Burt Bacharach and more on this record—are they accurate in these speculations? How much do you feel that what you’re listening to influences what you create?

I love all those people you mentioned and have loved them for a long time. They’ve probably been inspiration since day one, but they weren’t conscious inspirations. If there was a conscious thing, it would be the instrumentation. On the last record we synthesized everything; write a piano part or a cello part and then play it on one of the synths. But this time, we went with the actual instruments. That was the only conscious thing.

There’s references to specific musicians. “Kantori Ongaku” is a specific reference to Haruomi Hosono. Or maybe because it was like a “let’s do this country style thing” for “Kantori Ongaku,” I remember wanting to find a J.J. Cale kind of vibe. I love J.J. Cale, and we tried to approximate that. But our version is all speedy and is like a messy J.J. Cale. That would be the only person in a particular song that I can think of us going “let’s go for this kind of thing now.”

There seems to be a tendency for you to be labelled as a freak-folk artist, but your past few records—and Ma specifically—seem to be in a new sonic world that feels less “freak-folk” and more eclectic and “Welcome to Devendra Banhart’s Brain:” do you feel that freak-folk is still an accurate label? Do you feel a kinship with it?

I never, ever, ever did. I never once said it, never once said I was that. I didn’t make it up. It was always weird and airy to me, it made no sense. That being said, I’m freak-folk all the way, baby, oh yeah. The freakiest.

No, it’s dumb, it’s really dumb. I mean, it’s the stupidest label ever. But, I embrace it all the way.

How did it feel to hear that Carole King liked “Taking a Page?”

It made me want to go to Disneyland. It’s too much. To quote Little Richrad, “it made my big toe jump out of my boot.”

This interview was condensed and edited for length.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.