Videos by American Songwriter

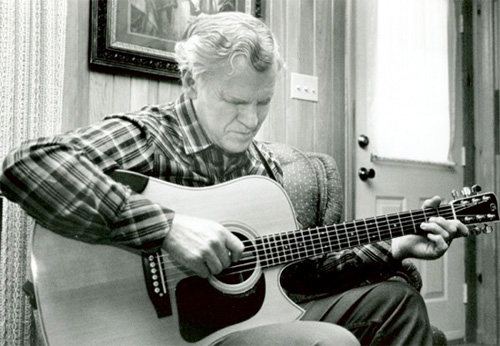

Critter Fuqua enrolled in college a few years ago to study the history of the English language, and maybe gain deeper insight into centuries-old folk ballads in the process. Before his recent return to Old Crow Medicine Show – the hot and with-it old-time string band he co-founded in 1998 and officially departed a little less than a decade later – he managed to get three-quarters of the way to a bachelor’s degree at Kerrville, Texas’s Schreiner University. “Not Shriner, like the little cars and little hats,” he volunteers. “Captain Charles Schreiner was a Texas Ranger and Confederate veteran and founded the school.”

Considering that college students are a prime demographic of Old Crow’s fan base, Fuqua couldn’t help but learn a thing or two from his classmates about the real-world impact of the music he’d helped create. “I ran into quite a few people that knew the band,” he says, “and especially knew ‘Wagon Wheel.’ I think more people know about the song ‘Wagon Wheel’ than about the band. … Actually, I found out the choir at Schreiner sang ‘Wagon Wheel.’”

Then there was the time Fuqua heard a circle of pickers tear into an off-the-cuff rendition. “Everybody started playing ‘Wagon Wheel,’” he marvels. “And no one really knew that I was in that band or had been on that record. It’s taken on a life of its own.”

It’s worth noting, in the age of digital music delivery, that the YouTube evidence backs him up. There are pages and pages of “Wagon Wheel” covers, from a live radio version by U.K. stars Mumford & Sons, to performances by a busking Canadian accordionist, a one-kid-band in a high school talent show and hordes of young bedroom and barroom troubadours. (You can even find a video of Luke Bryan – the guy behind the vile 2011 hit “Country Girl (Shake It For Me)” – struggling through the verses on stage.) Not only was this single from Old Crow’s self-titled 2004 album certified gold – for the below forty-set especially, it’s become a bona fide folk standard, eminently singable and shareable.

The way that Ketch Secor – Old Crow’s singing, songwriting, fiddle-playing, harp-blowing de facto leader – came to share credit with Bob Dylan for writing “Wagon Wheel” says a lot. It wasn’t like they sat down together one day and cranked out the easy-rocking country tune. In reality, a teenaged Secor discovered the “Rock Me Mama” chorus on an obscure Dylan bootleg and took it upon himself to add verses. By then, he’d developed the habit of writing what he calls “stolen melody songs” – like when he penned fresh, war tax-themed lyrics to a tune that had already passed through other wholesale re-writes during its descent from old-time Scots-Irish balladry. “That’s what I saw happening, so I just added my two cents,” Secor explains.

“‘Wagon Wheel’ was this culmination of these things that I’d learned how to do before, the application of folk music to my life, to the stories of my time. I really liked topical song. I learned that from Phil Ochs. He wrote songs about who was getting hacked up in the streets of his town in his time. But that didn’t change forty years later, after the Civil Rights Act. It was still the same stuff going on in my town, so I could tell the story with the same credibility. And I was just as removed, the young, white, folksinging kid that Phil Ochs was. So I had the audacity to write about it, too.”

Bear in mind that Secor and Fuqua – who’ve been buddies and collaborators since their junior high days in Harrisonburg, Virginia – were inhabiting a very different musical world than the earnest, tradition-emulating one of Ochs’s 1960s folk revival. By the early ‘90s, the atmosphere was one of adolescent angst and alienation from elders. Grunge rockers turned their wrenching emotions inside out for all the world to feel via abstract lyrics and distorted guitar riffs – the important part was they were playing their own songs, and thereby engaging in unvarnished self-expression. And here were Secor and Fuqua learning to play antiquated unamplified instruments and borrowing songs from their fathers,’ grandfathers’ and even great-grandfathers’ generations.

“I remember selling all my Pearl Jam records to get Bob Dylan records,” says Fuqua. “I went back in time and I started listening to Jimi Hendrix, because I knew he’d covered ‘All Along the Watchtower.’ And I started listening to all these Memphis and Delta blues players. And Ketch went down the road to the old-time Appalachian stuff and playing clawhammer banjo. Then we kind of met back up – I mean, not literally, but musically … It was a very organic kind of thing, and we realized we could put that energy that we loved in punk rock and Nirvana into what we were doing. And it wasn’t even a conscious thing like, ‘Wait, we can do this.’ We just did it, and it worked.”

At first, it was just the two of them egging each other on in their folky pursuits, but eventually, after a move to Ithaca, New York, they found enough likeminded twenty-somethings to form the band, a much taller order then than it would be now. When Old Crow busked on the streets, made DIY recordings and settled in Boone, North Carolina, the band members weren’t performing songs they’d written, but drawing on a storehouse of pre-war jug band, string band, minstrel show, blues and folk fare.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.