Videos by American Songwriter

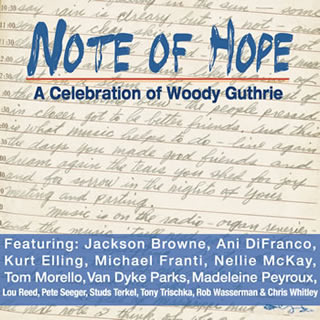

On September 27, 429 Records will release Note Of Hope, an album of Woody Guthrie’s writings set to music by artists like Lou Reed, Jackson Browne, Tom Morello and Pete Seeger, and spearheaded by Grammy-winning bassist Rob Wasserman. We spoke with Woody’s daughter, archivist, and album co-producer Nora Guthrie about assembling the record, Woody’s legacy, and what’s coming up next.

What was the reason for wanting to make another record from his unpublished lyrics?

I’ve done about seven or eight now using his unpublished lyrics. I did two with The Klezmatics, of Woody’s Jewish material and Brooklyn material. And I did one with Jonatha Brooke which had a lot of love songs on it, because Jonatha likes love songs. I did one in Berlin with an artist there in German. So it’s been this ongoing process going through the papers and turning the pages and going, “Oh my god, no one ever sang this.”

Woth Woody, who left so much behind because of Huntington’s disease, he didn’t have the opportunity to make anything of it or to share his ideas with people in that way. I felt like if he hadn’t had Huntington’s and he had just continued recording and singing these songs, I would be out of a job.

So that’s the emphasis personally for me… having that sense of responsibility, like when your parents die, you’re just like “Oh, what do I would with this?” And I guess with a song, the only thing you can really do with it is sing it.

How you decide on Rob Wasserman to spearhead the project?

I met him at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the year after they did the tribute to Woody, I think it was ’’97 or ’98. And the next year they did a tribute to Robert Johnson, and Rob was there playing with somebody. And I just had this notion, because I love the bass, the feeling of it floating like an undercurrent, like a wave under the ocean. It’s droning, or pounding, and it just keeps going and going. And all these things happen on top of it or around it, and sometimes you’re aware of the bass, and sometimes you’re not. Sometimes it’s just holding things together.

I wanted to do something subtle. With Jonatha it had been focusing on a woman’s voice and how a woman’s voice could sing Woody Guthrie’s songs and how she interprets them. But this was just this undulating bass I wanted to have, and the whole world is riding on this wave. Whether it’s hip-hop or rock or spoken word or an old man or a young girl or a jazz singer, we all exist riding on the same hope.

One of the things that I always have a little trouble with as a listener is when you have like various artists and a compilation. And as much as I like the idea of all these different people singing and stuff, sometimes they just don’t seem to have anything in common. You kind of just go from one track to the next track to the next. I thought maybe the bass and the words would be the continuity, and that all these differences would suddenly not seem so different, because they all had these two things in common.

There are some real activist artists on the records like Ani DiFranco, Tom Morello, Pete Seeger; was that a conscious decision?

One of the things I found are so many people are activists in their own ways. We just don’t hear about it. They each have a cause or a picket line that they’re involved with. Woody’s kind of activism is a 360 degree kind of activism — he’s not just focused on unions. But when you listen to Jackson Browne’s love song, when they’re sitting on the bench at night and the stars are shining and what is this young couple talking about and whispering into each other’s ears? Some of the lines are “and we talked about this and we talked about that, and we talked about the union. I was like “wow, Woody wrote the union into this romantic song.”

So you don’t have to be a political activist, you can be a lover and find ways to bring all these ideas and stuff into your conversation into your home and into your town. I kind of found out that all these people are activists in a way, and to me, the thing is to find words or a lyric that match up with that.

The idea is that when they sing it, it should sound like they wrote it. It shouldn’t sound like somebody else wrote it. It should sound like Jackson wrote that song, or Ani wrote that song. That’s what I tried to do. I tried to make such a match that when you hear it, like when you hear Tom Morrello singing “Revolutionary Mind” and you didn’t know anything about Woody Guthrie, then you’d go “that’s a cool song, did you hear Tom Morrello’s song?”

It seems like the unpublished stuff that gets turned into songs is so different from the Woody Guthrie music that we’re familiar with.

One of the weird things that happened on this album, that’s never happened before – I was working with Lou Reed. The way he records, he writes each line separately, that’s the way he likes to sing. So he took what we would call an essay and he just placed the lines straight down. And then I realized, that’s weird, every other line rhymes. But it was just a letter, it wasn’t like a lyric. I didn’t realize until after I reformatted it, but Woody was so used to writing songs that even in his letters ever other line rhymes. That was a stunning surprise. It was like stream of consciousness for him.

I remember a couple times I was trying to explain years ago what this would be. There was a producer in the room and I would just start singing the song, singing the letter, singing the story, just by myself. The original idea was that it would be very improvisatory, like jazz. We would go into the studio with people who were comfortable messing around words properly. And just kind of see what happened, between the bass and the structure of lyrics and words that we had.

What’s a track on Note Of Hope that you really love?

You know, I love them all. It was really the placement of all of them, because when I first started working on them, I thought of it like an operetta, like Smile or The Wall or Tommy. But things kind of flowed into each other and they also kind of reacted to each other. For me, one of the most beautiful moments, there’s a couple in terms of sequences — but when you go from the Van Dyke Parks instrumental, which is an overture, and then you hear Madeleine Peryroux singing the opening line: “Times are getting hard folks, they might get harder still.” I get goosebumps every time I hear that. Because it’s like the opening of an opera for me. Like in Shakespeare, some character comes out and says “this is a story about a king and a this and a that and this happens.”

Or the beauty of hearing Studs Terkel, his voice. Here’s this old man and he’s telling a story like grandpa and you’re sitting on his knee. He’s like all these old folks who are street wise. And then you have little Nellie [McKay] coming in like the innocent angel on the planet, looking at these old folks and responding to their love and what they’ve been through, and their hard and leathered faces and their graying hair and the kids running around the streets. The last line of her’s is “I wonder sometimes if anyone’s pleased with what we’ve done with our lives, when you look around.” Are our kids gonna say good job mom? Or are they gonna say, man that sucks, why didn’t you guys do something about it?

How much usable stuff is left in the archives? Do you plan to keep doing projects like this?

Yeah, I guess I’ll keep doing them. There’s a couple more coming out this year. Really different kinds of stuff. Sometimes I’ll do like a whole album or two albums with one group like I did with Billy Bragg and Wilco. But I do a lot of single songs too, with different artists. They’ll just have a single song on their record.

I think there’s like 3,000 lyrics in the archive. Probably you could cross off a couple of hundred that are not good, so I don’t have to think about those. But there’s probably like another 1500 or so that I could work with over the next couple years. It’s kind of a big task. It’s hard because timing is everything. Certain things you want to come out. Like with this album it was really funny. Rob and I started talking in 1998. This has been a process of 12, 15 years–getting this all together. It’s been through a lot of incarnations. We’ve had to rethink and go back and try this and try that.

It has to feel relevant. I don’t do it to make records–I’m not a record maker. I do it because some of these ideas need to be spread around. And I don’t hear a lot of other people coming out with these kinds of lyrics. Do you?

What are some upcoming projects for the 100-year anniversary?

Note Of Hope is kind of going to kick it off, because I think this album a nice overture to 2012. It really introduces a wide variety of voices. Then the next one that’s coming out is an album with Jay Farar. It’s done already and he’s gonna be releasing that in January. Jim James is a part of that, and Anders Parker. But I started working with Jay and the project started. He is like a totally different vibe. It’s so beautiful what he did.

Also we have a centennial website–Woody 100. It lists all the new releases that we’re doing. There’s a guy I’ve been working with in Austin, Texas–Jimmy LeFave. He’s kind of a rockabilly type. He’s finishing up his album with Woody’s lyrics now. A lot of that stuff is kind of Western oriented–about Woody’s life in the Midwest, and Midwest love songs.

Mermaid Avenue is coming out in March. There’s a box set with a third CD that we did. And it will have a DVD and some other stuff in it. Also, on the website you’ll see we’re working on a lot of books. I did a walking tour of Woody’s new york. Just all the places he lived and wrote songs. Like a walking tour guide. That’s coming out in May. There’s a whole bunch of stuff coming. We did an audio version of the walking tour. I found all this stuff that Woody made. It has a lot of interviews from when he worked with different people. It’s like an oral history of Woody’s time there. And also, we’re doing a lot of concerts in 2012.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.