Videos by American Songwriter

For more than three decades, Mekons have been a band that can do no wrong musically and no right commercially. Despite a hugely devoted fan base and respect from critics and peers, Mekons never caught on with the general public. In part, that’s because of their incredible stylistic diversity.

When you buy a Sonic Youth album, you know what you’re getting. A Mekons album could contain post-punk, folk, industrial electronic music or boisterous country-rock. But the exact thing that has kept them from becoming popular has also been a key reason they’ve been able to endure – they never chase trends and follow their muse wherever it takes them.

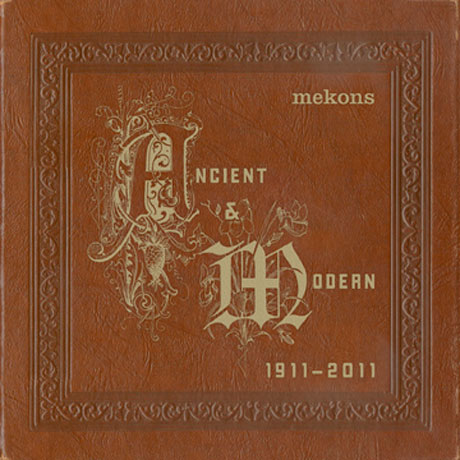

Their latest album, Ancient & Modern (out 9/27 on their own Sin Records), is a Mekons primer of sorts, with folk, country and rock all thrown into the mix. Lest you think they’re making it too easy for their fans, it also has a concept, comparing life 100 years ago to the world today. We talked with singers Jon Langford and Sally Timms.

Where did the concept for Ancient & Modern come from?

JL: Out of the communal swamp. I never really remember where anything generates. We liked the idea of looking at the modern world and the 100 years prior to that. We saw similarities from today to 1911, which was the calm before the storm of World War I.

ST: There was a shallow Edwardianism at that time, which was similar to how we feel about contemporary culture. It was a consumerist environment where people didn’t think or have to think about the consequences of things. Coming out of World War II, people had seen a great deal of loss.

I saw [British politician] Tony Benn talk in London. He was a member of the upper class, but he fought in World II. He talked about people who became socialist because of what they saw. Wealthy Westerners today don’t live through that, and middle class kids don’t have much concept either. Look at [British Prime Minister] David Cameron or George Bush. We have leaders now who have nothing at stake. They’ve lived lives of utter privilege. How can they make sensible decisions about governing society? We’re being failed by our politicians on a massive level.

How did you become interested in the pre-WWI era?

JL: There’s a song on our last album [“Natural”] called “Dickie, Chalkie and Nobby” that kind of touched on it. There seemed to be parallels between what happened then and what’s going on now. It’s almost Orwellian. People are oblivious to it. People are voting for the Republicans and sending their kids to die in wars without knowing what’s taking place. I defy anyone to explain why we’re in Iraq or Afghanistan.

ST: You can wander around England and see war memorials to people who died in Kandahar decades ago. Are we really destined to never learn from history or is it deliberate?

Do you want your album to make people think about these things?

JL: It’s not a conversation where music is somehow relevant. It’s obviously not relevant.

ST: No one buys our records. But even if no one really bought them, we wouldn’t make different records. This is what we have to do. We make records about what we’re thinking about. Does it make anyone change? Obviously not.

JL: We hope to be part of a conversation that hopefully still exists. But we’re basically powerless. I can march around Racine, Wisconsin, going door to door for Obama and feel like crap two years later when Guantanamo is still open and he’s escalating the drone campaign – or we can do this. We believe some sort of cultural production is important. Hopefully, it informs some kind of conversation, but I don’t have a lot of faith because they lid is on so tight.

The interesting thing about punk in 1977 is that the lid came off for about a year. No one knew what was happening, and that made us question what was going on. I’ve got teenage kids, and when I talk to them and their friends about issues that concern me they think I’m a paranoid loon. They don’t think there’s anything wrong with the world. They think corporations are benign. I’m not a conspiracy theorist, but they think I’m Ted Kaczynski when I ask “Don’t you worry that Facebook is doing this or that?” or ‘Don’t you worry there are chips in your cell phone?”

A lot of the bands you came up with, such as Mission of Burma and Gang of Four, found belated success. Why do you think more people don’t know about Mekons?

ST: Because we’re not as good as them. (laughs)

JL: We’re much better at being obscure. They’re compromising their obscurity.

ST: We were never a cool band. There was always an element of somewhat jester-ish humor in our music. Gang of Four was a much more cool band, even though they were not any more serious than we are. Also, we didn’t split up.

JL: Gang of Four is famous for a sound they created on a couple of albums. We have different sounds on different records. Ours is way of working that can produce almost anything. That’s what’s interesting to me about the Mekons. … If you split up, that helps. We should have split up for 10 years and gotten back together. Maybe we can still do that.

ST: Except we’d be dead before there’s any interest in us reforming.

What did you think about the Revenge Of The Mekons documentary? It seems that other people think about your legacy more than you do.

ST: It’s weird when you watch something like that. We have done a lot of things. It’s interesting to see it. There are so many stories you could tell. The film becomes the thing filmmaker chooses to focus on, but there are a million possibilities within it.

JL: We trusted the director. I said, “Just make sure it’s not boring. I don’t care what’s in it. Just make sure it’s not some grim worthy tale of four people who wasted their lives struggling.” Really, it’s been a great time, really good fun. I’m not a miserable person. I have a good time all the time. (laughs)

All of you have other projects you work on. What’s special about the Mekons?

ST: It doesn’t compare to anything else I’ve done on an artistic level. When you’ve known people a really really long time and been through loads of things and actually like them, that’s a great thing. None of us dislike each other but stay in this because of the music.

JL: It’s the opposite of The Who when they’d hate each other and travel to gigs separately, but were in it for the paycheck. We all like sharing grubby rooms and hanging out.

ST: I don’t think any of us as individuals do anything as well as when we’re combined together. I don’t love everything we do, but some of best things I’ve ever done are as part of this band.

JL: I do lots of things, but there’s nothing I like as much as The Mekons.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.