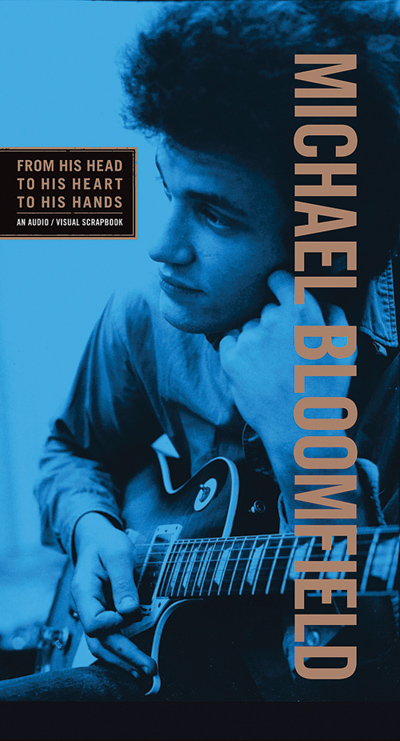

Michael Bloomfield

From His Head to His Heart to His Hands

(Columbia/Legacy)

4 out of 5 stars

Videos by American Songwriter

Michael Bloomfield, probably the most underappreciated of rock’s guitar gods of the 1960s, liked to call the music he played “sweet blues” because it sounded like singing – like tenderness – compared to the harsher “shouting” of his contemporaries.

And he really could put lyricism and sweetness, along with sumptuous variations of tone and effortless tempo shifts, into his solos. Moving between jet-speed chord changes, contemplative modal playing, single-note explorations and groove-cutting slides, he wasn’t so much showing off his prowess as showing his love for caressing his guitar. It was sweet, indeed.

He did as much to create blues-rock and make the electric guitar the focus of a band as anyone. His towering achievement, Paul Butterfield Blues Band’s 13-minute “East-West” (recorded in 1966), was a great leap forward for rock.

He died way, way too soon – at age 37 in 1981 from a drug overdose – and stopped being relevant to what was happening in rock about a decade before that. That wasn’t entirely his fault – he kept believing electric blues-rock could be a thing of beauty, played as inventively and thoughtfully as jazz, after the original audience for it tired of all the self-indulgent players.

There have been quite a few posthumous releases of his material, but on From His Head to His Heart to His Hands his friend Al Kooper – whose musical career and background as an urban Jewish lad taken with American roots music mirrored Bloomfield’s – tries to deliver the definitive retrospective. He spent years curating this project, which features three discs of music and a DVD documentary, and delivers the equivalent of the Ten Commandments of Bloomfield.

“East-West” certainly is here. One can wonder why Kooper chose not to include anything from Bloomfield’s high-profile but indifferently received 1970s collaborations Triumvirate (with John Hammond Jr. and Dr. John) and KGB (with Ray Kennedy, Rik Grech, Barry Goldberg and Carmine Appice). But one also must accept this as a statement by Kooper about the best of Bloomfield’s work. Indeed, it happens much of Bloomfield’s best work came in collaboration with keyboardist Kooper.

Bloomfield’s life poses riddles. How could anyone pick up guitar at age 13 and by 16 – still underage – be guesting with the greatest blues musicians alive in his hometown Chicago’s South Side clubs? By accounts presented in the liner notes, he was an enthusiastic polymath. Yet he was restless and got lost in the 1970s. There may or may not have been a connection between his tortuous insomnia and his drug use, which included heroin.

The film included in this package, Bob Saries’ long-in-the-works Sweet Blues, gets into Bloomfield’s motivations as best it can and is frequently riveting, but at just 60 minutes leaves questions unanswered.

He was signed by Columbia Records’ John Hammond as a solo act in 1964, but not much came of that, though Kooper includes several of the audition tracks. Columbia labelmate/admirer Bob Dylan chose him to play those fantastically punchy guitar licks that lift up the end of lyric lines in 1965’s “Like a Rolling Stone” and carry you, feeling a little higher each time, forward.

An early highlight of this package is the previously unreleased instrumental take of that song (with Kooper on organ), emphasizing not only Bloomfield’s contribution but also pianist Paul Griffin and drummer Bobby Gregg. Who needs singing with playing this good? And it’s followed with a version of “Tombstone Blues,” not only with Dylan singing but the Chambers Brothers joining him on choruses. This offers Bloomfield’s precise, piercing guitar solos and shows that his work is one reason Dylan was so easily accepted into the rock ‘n’ roll world in 1965.

Dylan certainly thought so. Included on the final disc is a previously unreleased track, from San Francisco’s Warfield Theater in 1980, where Dylan warmly introduces Bloomfield and then lets him play with eruptive force on “The Groom’s Still Waiting at the Altar.”

Kooper on the first disc also includes a good sampling of music from Bloomfield’s short-lived psychedelic-blues-band-with-horns Electric Flag (with Buddy Miles), including some unreleased live tracks that really throw sparks. The explosively liberating cover of Howlin’ Wolf’s “Killing Floor,” which begins with a snippet of an LBJ speech about “speaking tonight for the dignity of man” that then fades to laughter, is mandatory listening for anyone wanting to know what the late 1960s were about.

Bloomfield recorded actively in this late 1960s period, both under his own name and with others, and the package’s third disc rounds up some of the more driving cuts from miscellaneous sources, including “It’s About Time” (with Flag lead singer Nick Gravenites) from Live at Bill Graham’s Fillmore West; “One Good Man” from Janis Joplin’s I’ve Got Dem Old’ Kozmic Blues Again Mama!, and “Can’t Lose What You Never Had” from Muddy Waters’ Fathers and Sons.

The second disc is completely devoted to work that Kooper and Bloomfield (with others) made together. This is the heart and soul of the project. Kooper has chosen material from the two albums they released back in the day like the easy-going but swinging “Albert’s Blues” from 1968’s Super Session and the beatific, Coltrane-inspired “Her Holy Modal Highness (Live)” from the follow-up Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper.

But he also has gathered tracks of them together from various posthumous and expanded-edition releases put out since Bloomfield’s death. The inclusion of a Super Session version of “His Holy Modal Majesty,” which was added to a 2003 re-release of the album, features Bloomfield playing to Kooper’s exotic ondioline electronic keyboard. Also included here are two passages of Bloomfield explaining to audiences – in a charmingly spacey way – the origins of the performances they’re about to hear. It’s a nice touch.

And that brings up Bloomfield’s voice. Early on, producer Hammond discouraged him from singing and he took it too heart. One wonders if that was such good advice. Later in the 1970s, Bloomfield did sing in intimate club settings where he could play acoustic and electric blues, solo and with supporting musicians. On this package’s third disc, Kooper provides a generous sampling of ones recorded in 1977 at McCabe’s, a Santa Monica folk club, and released much later in America on an album called I’m With You Always.

The music is excellent, and he displays great comic flair with the short monologue “Men’s Room,” about the teenage girl who cleans up the bathroom, and with the hilarious self-penned blues tune “I’m Glad I’m Jewish.” He easily could have found a large audience in later years, had he lived, applying his rugged but expressive voice and incisive wit to acoustic blues, as David Bromberg has done.

But that was not to be. Still, From His Head to His Heart to His Hands shows that what Bloomfield did accomplish in his short life was not just sizeable but downright seismic.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.