The daughter of Yiddish poet Aliza Greenblatt, dancer with the Martha Graham Troupe, mother of Arlo, Nora & Joady, she was the first champion of Woody and the Woody Guthrie legacy

Videos by American Songwriter

It’s New York City, 1981, and we’re more than twenty floors up above 57th Street and the everyday mayhem of Manhattan. But here there is calm. And joy. And music. It’s the office she shares with Harold Leventhal, famed manager of legendary folk stars like Pete Seeger, Arlo Guthrie (her son), Judy Collins, Peter, Paul & Mary, and others.

“You want to see something wonderful?” she asked, with an impish glint in her eyes. “Look at this one.”

In her hands was a timeworn cherry-red spiral notebook. Inside were epic poems, song lyrics, romantic entreaties, expansive erotica, musings, jokes, sketches, drawings, all inscribed there by her late husband, Woody. Woody Guthrie.

For years they lived on Mermaid Avenue in Coney Island, where they raised their three kids, Nora, Arlo and Joady, and would take the train between there and Manhattan, where they worked. During those commutes, Woody would get busy, and devote all his exultant energy to filling entire notebooks thusly, dedicated to his beloved.

Woody’s old pal Pete Seeger said, “All songwriters are links in a chain.” But who did Pete learn to write songs from?

Woody.

Who so inspired and enervated a young Bob Dylan that he had to leave his Midwest home, change his name, and head east to start his life?

Woody.

She was Woody’s champion when he was alive, and she never stopped, even after his life was over. She startted the Committee to Combat Huntington’s Disease to fight the disease which robbed not only Woody’s life, but the last decade of his life.

She ran it out of this office which also housed Woody’s archives. There in big metal file cabinets was his universe of writing and drawing and love. There were the thousands of songs he wrote. There were also beautiful notebooks lovingly filled with endless pages of poetry and prose and erotica and cartoons.

Even the tools of his genius were lovingly preserved: his pens, pencils, crayons and notebooks. This proximity to the stuff of legend – to the cornucopia of expansive song wisdom and wonder that all poured out of this one miraculous little man – and the very crayons of this famous kid at heart – was thrilling.

She was born Marjorie Greenblatt on October 6, 1917 in Atlantic City, and lived till March of 1983. She danced with the Martha Graham troupe starting in 1935 under the name Marjorie Mazia. She first met Woody in 1940, as described in the following, and was with him on and off till the end of his life on October 3, 1967. She was a brilliant and beautiful woman, who put up with Woody while he was alive though it was never easy. He wasn’t a man who stayed still for long.

But long before he was gone, they both knew the legacy – the body of work – mattered. And though I was there before legions of great songwriters wrote new melodies to his unfinished songs, the lyrics which lived in the exalted archives, the recognition of his lasting legacy underscored all other endeavors.

Like Dylan who came to be with Woody before he was gone forever, I wanted to get near this source too, and Marjorie was used to all sorts of folk-inspired pilgrims being drawn to all things Woody. So she kindly allowed me to interview about Woody on more than one occasion, a dialogue which I am happy to include here.

After all, Pete Seeger was our hero growing up. He was in our world. But he always spoke and sang of Woody. And perhaps he cleaned up the dark aspects of Woody’s outlook more than necessary – Woody was no saint, after all- but what was undeniable was Pete’s respect for Woody as a songwriter. As the songwriter.

“Woody is just Woody,” John Steinbeck wrote. “He is a voice with a guitar. He sings the songs of a people and I suspect that he is, in a way, that people… there is nothing sweet about Woody, and there is nothing sweet about the songs he sings. But there is something more important for those who will listen. There is the will of a people to endure and fight against oppression. I think we call this the American spirit.”

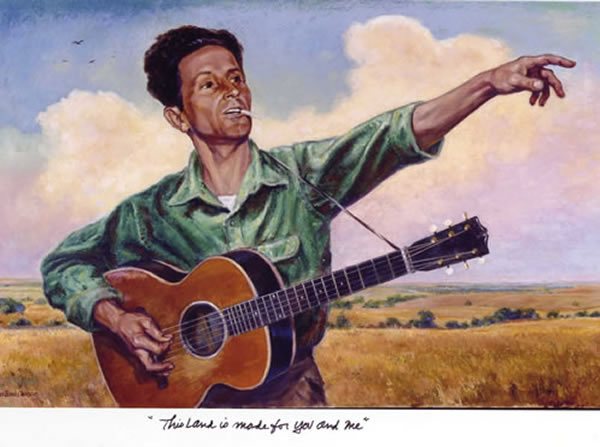

Woody’s work was remarkable — some 2000 amazing songs — songs of love, outrage, beauty, faith, humor, death, sex — and pretty much every other human experience under the sun. Some became famous, such as “This Land Is Your Land,” “So Long, It’s Been Good To Know You,” “Roll On Columbia,” “Deportees,” “Union Maid” and “Do Re Mi,” but most of his songs have hardly been heard once, if ever.

When he was married to Marjorie , he was so thoroughly in love with her that he’d write her entire inspired daily notebooks of love poetry and cosmic musings while on the subway, hurtling through the subterranean tunnels and overland tracks towards their Coney Island home.

Marjorie kept all of these, and every letter he ever wrote, and every song he composed, along with every crayon, pencil and pen he used to conjure his magic, in her New York archives, where she’d share it with his admirers, a legion of artists, musicians and vagabonds that increased every year, and continues to expand.

We spoke on a sunny autumn day in Manhattan. She sat at her big desk, always calm and joyful many floors above the tumult of a New York City business day. With generous patience and genuine grace, she considered each question carefully, and then answered.

AMERICAN SONGWRITER: It’s been suggested that, for both Martha Graham and Woody Guthrie, you were the organizer behind the genius.

MARJORIE GUTHRIE: This is true. Some people felt that Martha Graham was difficult to work with, but when you know you are in the company of a great artist, you minimize their negative aspects and are grateful for the opportunity to see how a true artist works. Let me say that she was a very good rehearsal for Woody Guthrie.

When did you first meet Woody?

On one of the Martha Graham tours, in St. Louis. My sister called me from Columbia, Missouri and wanted me to visit her. So I got Martha graham to let me leave the company for a day and I took the bus over to Columbia, and when I got there my sister said, “Oh Marge, I have to play something for you.”

And it is so vivid to this day: I sat on the arm of a chair and she played Woody’s “Ballad of Tom Joad” – first time I had heard his voice. And I was so moved, when it got to the end, I started to cry. I am an emotional person, and I love being emotional, and when he got to the end, I was just in tears.

I said to my sister, “How does anyone put into words what I’m thinking about myself?” Funny, I related it to myself: growing up, going through the Depression, seeing what happened to our family, coming to New York.

Then Sophie Maslow, who was with Martha Graham, had choreographed two of Woody’s songs from that same album, I Ain’t Got No Home and Dusty Old Dust, and she said to me, “Guess what – instead of using the record, I’m going to use Woody Guthrie, if he’ll do it, because he is in town. And I’m going to ask him to appear on stage with us and sing those two. “ And I practically fainted and said, “Woody Guthrie is in town? Sophie, I’m coming with you!”

I went with her and we came to what was then the Almanac Singer’s Center on 6th Avenue, a big loft with great big wide posts. First of all, they didn’t want to let us in. Finally, they did and I saw Woody from the back first.

He was looking out the window at 6th Avenue and he was nothing anything in stature like the way I pictured him. When I had heard his voice I thought of this tall, Lincolnesque figure with a cowboy hat. But then he turned around and he had this wonderful face. I loved his face immediately.

I don’t remember anything he said. I just kept looking at that face. And then remembering that voice and the quality of those songs. I fell in love with him right then and then. And he said to me late that when Sophie and I came up he was talking to her but looking at me. And I was looking at him.

In a few days he started to rehearse with us.. He was to be both a narrator and a singer in a production called “Folksay.” And here I loved this guy and everyone was picking on him. Why? Because he sings the song differently each time. Here we have twelve people on the stage and he puts in an extra verse, he takes out a verse. What do you do? Everyone was angry with him. I was just dying for him.

What I did was to take cardboard sheets and type up all the words of the songs and put them in measures and say, “Woody, why can’t you sing it just like the record?” He would say, “The day we made that record, Lee Hays has asthma, someone had just given us $300, and we were on our way to California. I don’t have asthma, I don’t have $300 and I’m not going to California, so I can’t play it the same way.” But I worked with him, using these little cards and before you knew it, we were living together.

What was he writing during this period?

That was the year he was writing Bound for Glory. He would be writing – by hand – and I would come home in the evening and he would read me what he had written. Then we would take turns, reading and typing. It was then that I first learned about his mother and all of her problems, and that she had Huntington’s Disease.

Was he a disciplined writer?

Oh yes. Take a look at any of his notebooks. He loved to write. He had great respect for his work. He signed every piece of paper and dated almost everything and wrote a little background about each song, like why he had written it. He did have a highly organized mind.

So he had an understanding of his own historical significance?

Absolutely. We used to tease about it. He would say, “We can be poor now, but maybe someday this stuff will be worth something.” But you see, even knowing that didn’t stop him from doing things the way he wanted to. And that was something else that I loved about him. You see, in the Thirties and the Forties dancers were the poorest people on the cultural ladder, and I didn’t have much. But that didn’t matter to me because the dancing was so important.

Woody had that same feeling. It wasn’t important whether everyone loved him or every songs made money. It was important that he was doing what he wanted to do, and what he was compelled to do. He couldn’t have done anything else anyway.

Did he have moments of self-doubt?

Very few, I have to tell you. He had confidence in what he was doing, that there were important songs, not whether they were commercial successes or not. That he didn’t know about. But what he knew was that in his songs were the voices of people he had known, and he felt better suited to represent these people than anyone.

Could he take criticism of his work?

He would argue with me. Very rarely would he change something. In the song “Jesus Christ,” I felt that one verse was wrong, that it misinterpreted Christ. He argued with me about it and won the argument. But he let me argue.

Did you have a sense of how famous he would become?

I never thought of him being famous commercially. I always had the feeling that when you speak for the down-trodden, you might be famous among the down-trodden but nobody else hears about you. And again, I don’t care. I wanted him to do what he was doing, and I felt that what he was saying was important. But the first hint of his real importance didn’t come from me or him. It came from Alan Lomax. It was Alan who said to me one day, “Don’t throw anything away. Save everything.” And looked at him as if to say, “Why?” And he said, “Woody is going to be very important.”

I knew that what Woody wrote was good because it moved me. But it would move other people too, and maybe cause them to want to be “wherever little children are hungry and cry.”[From “Tom Joad.”] When Alan said that to me, it was the beginning of my appreciation that other people loved what Woody was saying.

He already had a little recognition when he came to New York. I was not yet involved with him; he was here with (his first wife) Mary. He had a radio show, the “Back Where I Come From” show, and he was commercially successful. But he left this show and he let me know why. “They wouldn’t let me say what I wanted to say, or sing what I wanted to sing, so who needs them?”

He gradually started receiving recognition, especially after the publication of Bound for Glory. Did that change him at all?

It didn’t change him, but he was very pleased. He wrote “My first copy” in the first edition of it. He was very proud of himself, especially when people began reading it and enjoying it.

Besides writing songs, he was always writing letters and poems and doing drawings. Which was most important to him?

The songs were most important. They came first. He had a wonderfully organized system, something most people don’t realize. Every morning he read the paper first thing. Then he would tear out of the paper things that he wanted to write songs about, and then make a list of songs that he was going to write.

Then he would write a few songs, read some of the books that he had gotten from the library, usually two or three at a time. He would read standing up because he got tired of sitting. Then he might sit down again and do some writing.

Yes, there were times when he did so some drinking and when he did, it had a very bad effect because of the Huntington’s Disease. HD puts you off-balance and drinking puts you more off-balance, so Woody was sometimes very off-balance.

Woody’s writing has a dizzying, almost drunken power to it. Do you think the HD affected his style?

No. I don’t agree at all with the suggestion that Woody wrote the way he did because he had HD. It does sound logical, but even with Martha Graham I saw the same kind of intensity and determination and creativity that Woody had. And look at Whitman and Jack London. They didn’t have HD and yet they had similar writing styles.

Also, he was encouraged by Joy Home, who edited Bound for Glory. She said to him, “Woody, don’t worry about what I’m going to cut out. Whatever comes to your mind, just do it.” And he enjoyed that freedom to just let it go.

I read that she’d suggest a few changes and he’d return with a hundred new pages.

That’s right. And she would say, “Woody, why didn’t you bring them in yesterday?” And he would say, “Well, because I hadn’t written them yet.”

Did he talk the same way that he wrote?

Nothing like that. Nothing like his writing. We were opposites; I am as verbal as anyone can be, and he was just the opposite.

If he were sitting with us right now and you were interviewing him, he would probably answer in a very slow, halting voice, kind of like [very slowly], “Yeah… welllll…. Way back…” Nothing like the flowing quality of his writing. He simply loved to write. He loved pencils, paper, typewriters. You know, I have to show you something. [Brings a box of pens and colored pencils.] This is all Woody’s. He loved this stuff.

Did he have dry spells ever, times he wasn’t inspired to write?

Very few. He was always churning them out, as you can see by the archives, which hold about two thousand of his songs. And he was just as creative a father as he was a musician. He could spend a whole day of the beach, starting with just our three kids around. By the end of the day he would have these tremendous sand castles, and about thirty kids who helped him build them. And they were beautiful, really beautiful.

Was it because he was so much of a kid at heart, himself, that made him so great with kids?

Yes, for sure. He had a great sense of playfulness, of fun. And both of us have great respect for young people because you are tomorrow, you are it. Anything we had is going to die and go away before you know it, but you have years ahead of you.

It is true that Woody and your mother wrote a song together?

My mother, who was a Yiddish poetess, wrote the words to a song and he corrected her. They didn’t write it together. It was called “I Gave My Sons To The Country,” and he was opposed to it. “Why do you want to give your songs to the country?” he asked. “Shouldn’t that be the question?” But my mother was really a much better writer in Yiddish and Woody never really knew this.

It was astounding to see all the letters he wrote you; the full notebooks of love letters and poetry and erotica he would fill up for you.

Every night when I would come home (commuting from Manhattan to Coney Island), I would look forward to two or three letters from Woody, especially when he was in the Army. I was a woman alone and it was wonderful to have these. But you know, I am a prude and I used to die from embarrassment all by myself. Nobody would be in the room but I would be reading those sexy letters and I would be dying.

And then he would say to me, “Why don’t you write back in turn?” And I would say, “I can’t write those kind of letters!”

I know Woody was a great fan of Chaplin. He always seemed Chaplinesque himself—

You’re right, he was very Chaplinesque. You know, he used to play the harmonica and dance at school when he was a kid. And don’t you think Arlo did the same thing when he was a kid? Certain people have that elfin quality. Arlo had it as a child; Woody had it all his life. Kind of half-singing, half-dancing, I’m the little guy on the block, but I’m no dumb-bell.

In 1969, Arthur Penn made a movie out of Arlo’s great song, “Alice’s Restaurant,” starring Arlo.

Yes. I loved that film, because there was a lot of truth in it.

There’s a scene in the film where Pete Seeger and Arlo come to Woody’s hospital room and sing, “Car Car.” I’ve read that Woody loved hearing the song “Hobo’s Lullaby” the most.

They sang all those songs and more. They sang a lot of songs. The only thing that wasn’t accurate was showing Woody in a private room. How I wish he had a private room and his own nurse!

I know that in addition to Pete and Arlo, a lot of other musicians came to Woody’s bedside during that last decade when he was at Greystone in New Jersey. Most famously, Bob Dylan made the trek to meet his hero. What were your impressions of Dylan from then?

He impressed me with his quality and intensity. I knew that he was determined. I didn’t like his diction when he sang, and I couldn’t understand the words. But I loved many of his songs and I felt that he was a creative artist who was going through, even now, the ups and downs that an artist must go through. Everything that you do isn’t always top-notch.

At first did Bob seem like just another Woody imitator?

Well, I had already spent a couple of good years with [Rambling] Jack Elliot, who Woody said was more like Woody than he was! But I had no resentment whatsoever of people imitating Woody, because if you are around a great artist, their influence is bound to get to you.

It’s like osmosis. Later in your life maybe you can find your own style. After all, I learned to love dance from someone who learned to love dance from someone who learned to love dance and so on. You must carry on the tradition of whatever you are doing and do so with integrity. I think Bob did that.

Woody’s life ended too early, and during his last years he wasn’t able to work. Had he more years, what do you think he would have done with them?

I can’t answer that easily. Woody would have changed with the times like everybody else to a certain extent. And Woody loved all kinds of music, something that not everybody knows. Moses Asch, who was a kind of mentor to Woody, gave him many free classical albums, and often I would come home and find him listening to Prokofiev. He knew Romeo and Juliet backwards and forwards.

He liked all different kinds of music, depending on what time of day it was or what he was doing right then. Nothing can better express the essence of the moment. Music is the soul of man. Woody used to borrow music from everywhere and change it around a little for his own songs. But it was the honesty and the quality of the songs that mattered.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.