Videos by American Songwriter

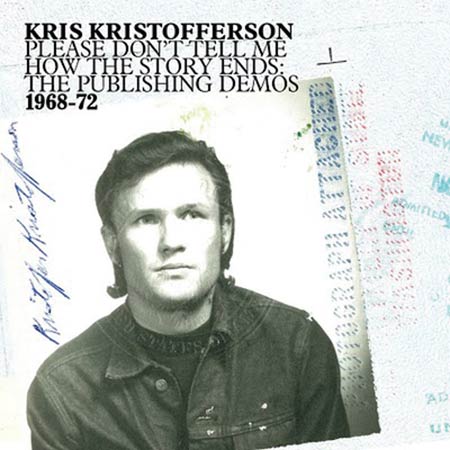

KRIS KRISTOFFERSON

Please Don’t Tell Me How the Story Ends: The Publishing Demos 1968-72

(LIGHT IN THE ATTIC)

[Rating: 4.5 stars]

The young Kris Kristofferson on the cover stares off to the left, shoulders hunched and mouth drawn, presumably looking pensive because he’s sitting for an official portrait and the atmosphere is the antithesis of stimulating. But nothing in this elaborate collection comes off as the least bit uptight—not the commentary of his cohorts, peers and admirers in the lengthy booklet, not the songs themselves and certainly not the performances, none of which have been released before.

At the time Kristofferson made these recordings, he’d strayed radically from the path laid out for him by his education as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, his Army captain rank, the West Point teaching position he’d been offered, the expectations of his Air Force major general father and the obligations of his own growing family. He had, quite simply, cut himself loose. There was no more script; just space cleared to wrestle through writing a new one for himself, and for country songwriting, especially the language and imagination of it.

Kristofferson was young then, but not too young—in his 30s, instead of his 20s—and an against-the-grainer transitioning from being a struggling songwriter who also tended bar, swept floors on Music Row and flew helicopters onto oil rigs in the Gulf into being the songwriter whose works just about every important voice in Nashville—and plenty more beyond—wanted on their albums. Much later—just six years ago, to be exact—he would become a Country Music Hall of Famer. It’s a revelation to hear the sound and spirit of what went on behind the scenes during that heady period.

Please Don’t Tell Me How the Story Ends starts off with “Me and Bobby McGee,” but the 16 tracks don’t, for the most part, retread the usual sort of Best-Of-Kristofferson territory. The song is familiar, not least because of Janis Joplin, but this rendition isn’t. He cut it just after he wrote it, in the middle of the night, with Billy Swan, who—along with a few other stalwarts, like Stephen Bruton and Donnie Fritts—appears on the tracks that are fleshed out beyond just Kristofferson and his guitar. The standard-setting hippie hitchhiking ballad takes an eerie turn when a parlor organ pad and a reverb-numbed chorus of backing vocals waft in, then take off on their own, way, way ahead of the beat. Lord only knows what they were doing in the studio that night—besides recording.

The song’s most iconic line is “Freedom is just another word for nothing left to lose.” And that unfettered, all-in way of thinking, feeling and being is at the heart of most of these songs. Freedom was a thing Kristofferson wrote about a lot, whether he spelled it out, as in “Me and Bobby McGee,” or vividly described what it was and what it wasn’t without actually naming it, as in “Border Lord” and “Slow Down.”

He pondered the lives and tragic ends of others, besides Bobby McGee, who wouldn’t be hemmed in by straight-laced society in songs like “Billy Dee” and “Epitaph (Black and Blue),” the latter written with Fritts as the news of Joplin’s death sank in. In “Smile At Me Again” and “When I Loved Her,” he turned his songwriting inward toward self-examination, philosophizing and romanticizing. And through almost all of it, he wrote lyrics that deepened and enriched the stories with a literary sensibility. These were significant developments indeed for Nashville songwriting.

Current country songs invoke revered Outlaws like Johnny Cash so often that it’s become all but an empty gesture. But when Kristofferson ran down a list of his favorite singers and songwriters of the moment in “If You Don’t Like Hank Williams”—and besides Hank and Cash, they range from “Bobby Dylan” to Bobbie Gentry and the Beatles—he was really making a statement, and staking out a meeting ground for renegade music-makers of many stripes. Which was also a rather different move for Nashville.

“Just the Other Side of Nowhere” is one song on this set that feels more right than it did when Kristofferson made a proper recording of it a little later on. He sings about being all alone and sorely out of place; seeing as it’s a guitar-vocal demo, there’s no reverb or accompaniment concealing the pockmarks in his baritone or dressing up the just-right nonchalance of his performance. The touch of jazz sophistication in the way the melody and chords move is a reminder that he wasn’t only applying his brain power to the words. His hushed, tender demo of “The Lady’s Not For Sale” is another that’s more affecting as-is.

Demos being what they are—that is, meant for demonstration, test-driving a song, rather than for entirely public consumption—there are plenty of loose and candid moments here, like the drifting harmonies of “Me and Bobby McGee.” A hard “p” overdrives the microphone during Kristofferson’s soft, pleading rendition of “Please Don’t Tell Me How the Story Ends,” and necessitates a redo.

But nothing compares to the mayhem of the final track, “Getting By, High and Strange.” It opens with three false starts, followed by Kristofferson’s ultra-cool reassurance that they needn’t go to the trouble of starting over: “We got lots of tape, man.” His finger-picking clicks on the guitar’s pick guard throughout, providing an erratic rhythmic counterpoint. And just when it seems like the song’s over, things really get wild; Kristofferson and his raggedly energetic harmonizers explode their call-and-response pattern and start testifying like countercultural charismatics.

The beauty of the album is the opportunity it affords to get as close as possible to Kristofferson’s inspired and game-changing songwriting moments, completely apart from the hits they became for Ray Price, Johnny Cash, Sammi Smith and countless others—or, for that matter, what they became on his own albums, which never quite seemed to chart as high or sell as well as a lot of the covers did. To hear his songs like this is the most natural thing in the world.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.