Videos by American Songwriter

Chris: But you made records on two-track when you didn’t know half what you know now. You have the knowledge and technique to make records without all this stuff. Don’t you think that might put something into the music, might be an actual advantage? With the Let It Be album years ago the Beatles made a conscious attempt to get back to basic recording techniques.

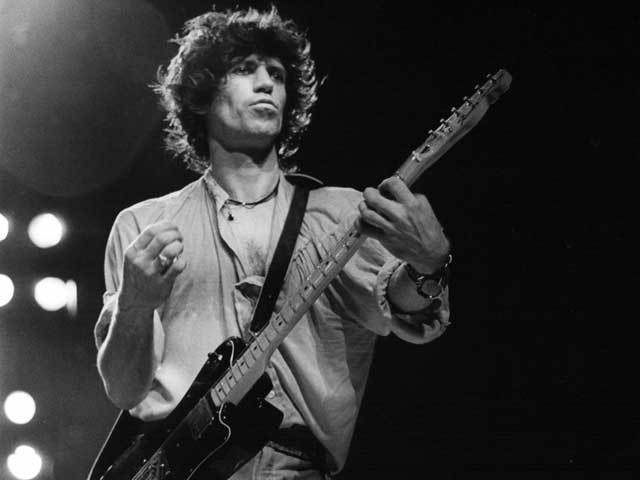

Keith: Well, “Street Fighting Man” was cut on a cassette player and you know what they were like in those days! The first little Phillips ones, you know. There’s a million possibilities—like overloading an acoustic guitar instead of using an electric guitar. You can get that lovely acoustic dryness and feel but with an electric sound. To make a rock ’n’ roll record, technology is the least important thing. As far as technology is concerned we keep it to a minimum. We’re the kind of band that you don’t . . . . We sound terrible if you try and make it techno-pop with us!

Chris: I didn’t notice on the last couple of albums you’ve been using a kind of rockabilly slap-back echo on the lead guitar, which I quite like myself.

Keith: Yeah, right, that analog-delay thing, yeah. The only new technology that interests me is when it sort of throws me back soundwise. And I can think, “Wow, that means I can go onstage and sound like Scotty Moore now and again!”

Chris: Looking back, what first got you interested in music?

Keith: I was twelve or thirteen in 1957 when rock and roll first really hit in and as you know, up to that time living in England it was “How Much Is That Doggie in the Window?” But my mother always had good taste in music. At home I can remember listening to Billy Eckstine, Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald and stuff every day, ’cause that’s what my ma would play around the house, singing away doing the dishes. And then her father, my grandfather, Gus Dupree, had a dance band in the Thirties, and whenever we’d go visit granddad there’d be a piano, fiddle, guitar, you know. He was probably the one who got me on guitar. I wouldn’t be surprised if he had a long-term plan for it, ’cause I always used to think this guitar was always sitting in the corner of his room, and then I found out only a few years ago that he only used to bring it out when he knew I was coming. So I sense a conspiracy there.

But I didn’t really start playing an instrument until, really we’re talking about ’57–’58, when I started to actually sort of touch the guitar. Although, as I said, I was brought up not unused to having musical instruments around and just going sort of plink-plonk-plonk and, you know, bang-bang wallop.

Chris: But when you first heard rock music, didn’t something inside of you click? I know it did for me.

Keith: Exactly.

Chris: …and everything prior to that seemed to be a time of total innocence and then suddenly there was a whole new thing going on.

Keith: And you wanted to know where the fuck it came from. And because there wasn’t so much of it, you weren’t swamped with it and you would say, hey, I really like that “Sweet Little Sixteen” and trace it back and you find out that this guy Chuck Berry comes from a record label that also has these guys like Muddy Waters, and it made us English guys a little more conscious of the history of the music just because it was such a bombshell when it first hit.

Chris: And in the Fifties in England, we used to be embarrassed about not being able to come out with a good rock record.

Keith: There were only a few guys that could sound convincing.

Chris: And then all of a sudden with the Stones and the Beatles . . .

Keith: Yeah, ’cause we were the ones who were twelve or thirteen when rock first hit, so it took those six or seven years for it to seep through and get the chops right.

Chris: Did it surprise you when you realized that America was picking up on this stuff that you’d…

Keith: Oh yeah, we couldn’t believe it that we were actually going to come to America and work. To most English guys at that time, America was this half-fabled land. And then later to actually work and record at Chess in Chicago, the same studio that Chuck Berry recorded in—amazing.

Chris: What was the attitude of those guys at Chess to you guys?

Keith: Pretty much disbelief on both sides. They were just knocked out that some white kids from England knew more about their music than American kids, they just couldn’t believe it. So it was a little bit of a shock all around. We didn’t know how long this thing would go on so we went for it gung ho! Charlie came to New York and hung around at the Metropole and Birdland fulfilling all of the old dreams.

Chris: I saw an old clip of one of your live Ed Sullivan Show appearances recently on MTV and it made me wonder just exactly what Brian Jones’ role was in the early group. ’Cause when we started getting original songs it was always Jagger/Richards, never a Brian Jones song, and although he was obviously a charismatic performer and had this great image thing, when it came down to writing and performing it was always you up front with Mick and you were usually playing all the leads. Was this a gradual change that came about when you and Mick started writing? It was surprising to see him in such an obviously subordinate role.

Keith: Yeah. He never got ’round to writing. I sat down with him a couple of times and tried to write with him, but…You see, I personally believe that most people that play an instrument would be able to write a few songs here and there. But they say, “I tried, I can’t do it” and give up and don’t try it again; they get too discouraged. But for myself and Mick it became a matter of, almost, necessity. It was Andrew Oldham who made it very apparent very quickly. He said you really got to buckle down and try and start writing songs because another album or two and you’re going to be forever at the mercy of other songwriters. You’re always gonna be hunting around for material. So the first song, “As Tears Go By,” was a great encouragement because, moldy old ballad as it was in its way, it did come out as a record and did all right. And that’s all you need to be able to say “Okay, I’m a songwriter as well.” But Brian was the one who was most affected by becoming a pop star. One minute he was a real back room jazz boy and then within a very short time it seemed to me he felt his main job was to be a pop star. He got less into playing and more into flitting around. He became very adept at leaping onto a vibraphone or xylophone in the studio and being able to knock it out. And in that way added a lot of interesting texture to some of the earlier records. It seemed he thought, “I’ve made it, I’m a pop star, that’s really what I do.” I suppose a bit of him inside, well, maybe there was a little bit of self-contempt: “I’ve sold out, therefore I’m not gonna concentrate on playing anymore.”

Chris: Well, he was always the blues purist, wasn’t he?

Keith: Very much so, yes. He would never even listen to Jimmy Reed, and hardly any of Muddy Waters’ electric stuff. We turned him on to Jimmy Reed and Bo Diddley. He was into guys like Sunnyland Slim and Tampa Red. Elmore James was about as far down the road as he’d gone with electric blues. Even people like Buddy Guy—I think he thought they were too showman-y. Chuck Berry, too. But he did get into it. I had a lot of trouble in those days, and I nearly didn’t even get in the Stones because I insisted on banging out Chuck Berry songs. “We don’t want no rock ’n’ roll ’round here,” he’d say. But I got through that one pretty quick. For a while he was ostracized from the blues purist societies of London for that. Mind you, so was Muddy Waters for a while.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.