Designed by Malone, New York-born artist, and musician Bjorn Copeland, the cover of John Cale‘s 18th album POPtical Illusion is a motley collage snapshotting a clear blue sea, camera lens, architectural archways, domes, and more abstract placements—the Velvet Underground co-founder’s eyes split in two and horse hooves. The pop-art pastiche sketches some of the visual and sonic perceptions revealed in the 13 vignettes on Cale’s album.

Just like Paris 1919—Cale’s third solo outing since leaving the Underground five years earlier—was his first of many exploratory deliverances to come, a montage of orchestral-pop post-World War I Western European culture and Dadaist and Surrealist pieces, POPtical Illusion is proof that Cale, now 82, hasn’t finished exploring different artistic, humanistic, and un-parochial concepts.

His second album in less than a year since releasing Mercy in 2023, POPtical Illusion is a classic, Cale hodgepodge of offerings, blending pop, rock, and a labyrinth of organs, piano, and synth.

On POPtical Illusion, Cale was tasked with sifting through 80 songs he had written, filtering it down to 13. “I went through a lot of them, and I was really trying to find a common … the 13 that fit together,” shares Cale. “They didn’t have any highlights within them that made sense as a group.”

There’s a “bit more humor in this one,” says Cale, comparing POPtical Illusion to the more dystopian Mercy. Picking up from the slow menacing march of “God Made Me Do It (donʼt ask me again)”—a title he admits was a “throwaway line”—the Tom Jones groove “Davies and Wales” is an homage to Cale’s home country of Wales. “It’s really about how I approached all the humor in what happened in Wales, and my background, and the characters that I remember,” says Cale. “It’s how I dealt with that humor that was going to decide whether this album was going to have as much energy as the last one.”

Videos by American Songwriter

The song has a deeper context for Cale, who has some guilt about leaving behind Wales in the early ’60s and moving to America and losing the language. “I feel bad about that,” says Cale. “It comes back to me in strange places. I’m falling asleep at night, and when I wake up in the middle of the night and this Welsh phrase comes roaring back. The language is very different, and I’ve got to approach it with some respect and a degree of attention because I speak English most of the time and I regret it. It’s like ‘Hey, do something about the language you had.’”

“Calling You Out” delivers a more soulful jazzy refrain showcasing Cale’s falsetto, while the easier listening swoon of “Edge of Reason”—Seeing mankind is not so kind … can’t you see the light … show me where the pain has been / Seems we’ve gone too far to fix it—and “I’m Angry” are more “serious” songs, reveals Cale. “It’s about how you deal with apologies,” he says of the latter track. “If you mess up the apology had better be real.”

Tender pop melodies twist around “How We See The Light,” before the perilous “Company Commander,” a favorite from the album, admits Cale, who breaks through its static: The right wing is burning their libraries down …when did we lose control of things. Some Velvet vibes fit around razor-sharp riffs on the cheekier “Shark-Shark” and the new-waved synth of “Setting Fires,” a song Cale says offers a more “genteel energy.” More obscurity abounds on “Funkball the Brewster” and the chant-worthy dance of “All To the Good,” which has a “religious note to it,” says Cale. “But I didn’t mean it that way.”

The penultimate “Laughing In My Sleep” dials things into another jazzier fix and is Cale’s wake-up call. “It’s an incongruous situation to be in,” he laughs. “If you’re trying to enjoy your life or the way it is you don’t want to be asleep.” POPtical ends on a different note, a piano dripping ballad “There Will Be No River” leaves off With me floating in the water / Like a magical piece of code.

“All of these come from the same place in the sense that they’re really about grooves,” says Cale of the album. “I start with a groove, and if you have the lyric and your music, the groove is really what holds it all together. But you still have to choose which direction you want to go in. And sometimes they don’t make any sense.”

[RELATED: 4 Songs You Didn’t Know Lou Reed Wrote for Other Artists]

He continued, “This one [album] has more regression than usual. I like the energy that’s in there. I’ve been trying to get to that energy for a while and I managed to tap it, and I’m glad I did because it stuck with me.”

Most of the material Cale has written since finishing POPtical Illusion has been more aggressive. “I don’t mind having nonsensical ideas. I think your solace as a human is a sense of awkwardness and a lack of discipline. And that lack of discipline opens up doors for you that you’re not sure of.”

For someone who started out writing songs with former bandmate Lou Reed, who was working for Pickwick Records artists—including Cale’s earlier outing The All Night Workers (“Why Do You Smile Now?”)—before making their way to the Velvet Underground and their collaboration on songs like “Sunday Morning,” “Here She Comes Now,” and “Sister Ray,” nothing needs to make sense to sounds great.

“The one thing that I learned was the brevity of a song,” Cale says of songwriting. “I had a lot of times where I had songs that were really short. I was being told ‘That’s too short. You can’t have that.’ I just insisted on it being short, because some needed a certain brevity that allowed the song to breathe, and to be, and that exists in a different space than all the other times I’ve come up with them.”

Leonard Cohen comes up. Cale references his 1984 classic “Hallelujah,” and its verbosity. Cale covered “Hallelujah” on the 1991 tribute album I’m Your Fan: The Songs of Leonard Cohen and later on his 1992 album Fragments of a Rainy Season. “It was pretty funny,” remembers Cale when he first approached Cohen to cover the song. “I asked him ‘Can I get the lyrics to Hallelujah? I need to make a record of it.” He sent it to me and I said ‘Holy cow, this is 15 verses.’ I asked if I could take some of the lyrics out because some were quite religious, and they didn’t fit with me at all, but a lot of them were really beautiful as usual.” Cohen ultimately gave Cale carte blanche to pull out what he wanted.

“I like messing around, and sometimes the language doesn’t flow,” says Cale of his journey through songwriting. “There are some lyrics that have been a little torturous, and there were some that were nonsensical, but I didn’t fight it. When you don’t have a clear idea of where you’re gonna go, you can come up with some surprising things in the end.”

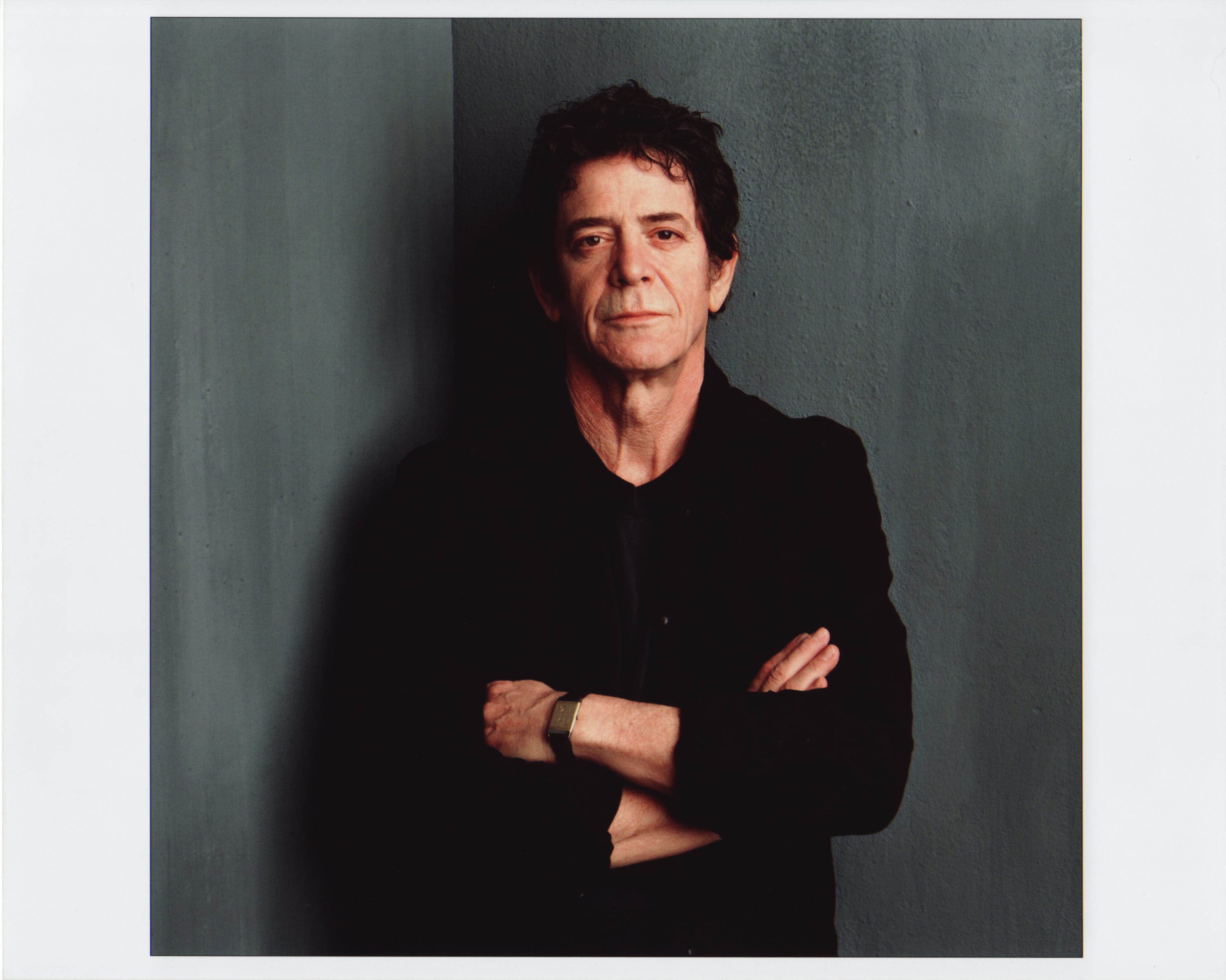

Photo: Michael Kovac/Getty Images for NARAS

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.