Videos by American Songwriter

Like Lennon and McCartney, Bacharach and David, Leiber and Stoller, Weil and Mann or Goffin and King, who also figure prominently on that BMI list, Webb’s career began in an era when writers cranked out tunes like Detroit cranked out cars. Disposability was a big concept back then; the notion of crafting timeless classics was only slightly less foreign than the idea of celebrating song-slingers in halls of fame.

“When people would ask me, ‘How do you think you’ll feel about your music in 50 years?’ I would say, ‘What? Are you talking to me?’” Webb says, slipping in a quick DeNiro imitation. “I could not foresee that sort of a lifespan for any of my songs. To me, it was like McDonald’s, like fast food. We write these things and they go up the charts and we write some more and they sort of disappear.”

The son of a Baptist minister, Webb played organ in his dad’s church. Rewriting hymns led to more experimentation. When he headed from Oklahoma to Los Angeles, he was still a “skinny country boy” in his teens – just bold enough to “take a shot in the dark” at the West Coast office of Jobete Music, Motown’s publishing house.

In two years there, he wrote 45 songs; the first one recorded was “My Christmas Tree,” on a Supremes Christmas album.

“All the technical aspects of songwriting, I learned right there at Motown,” says Webb, who now chairs the Songwriters Hall of Fame. (In 2003, he received its Johnny Mercer Award.)

Shuffled out of Jobete with his mentor, Mark Gordon, Webb went to work at a recording studio. He remembers contributing piano on a 15-hour Rod McKuen session, earning $52 – a buck per song – before sweeping up and closing the place. But Gordon had told him to hang in there, and showed up one day with Johnny Rivers in tow.

“Before they left, they not only bought my contract, they had the choice of four songs and they took ‘Didn’t We,’ ‘Up, Up And Away,’ ‘By The Time I Get To Phoenix’ and ‘The Worst That Could Happen,’” Webb says. When Rivers recorded “Phoenix” in 1966, the song was already two years old. But it was Campbell’s cover, and the 5th Dimension’s lofty “Up, Up And Away” harmonies, that carried Webb to stardom the following year. They earned eight Grammys altogether, including the latter’s Record and Song of the Year. Both were nominated for the top song award.

“I was sure I wasn’t going to win,” Webb recalls. “So I was very sanguine about the whole ceremony … And I’m sitting with Jay Lasker, an old-time record mogul type at ABC-Dunhill. He was always chewing a stogie and he had big black horn-rimmed glasses; he was really a stereotype. And he said, ‘Well, kid, are you excited?’ And I said, ‘No, I know I’m not gonna win. How can I win? I’ve got two songs nominated.’ And he leaned over to me real close and said, ‘Kid, it’s in the bag.”

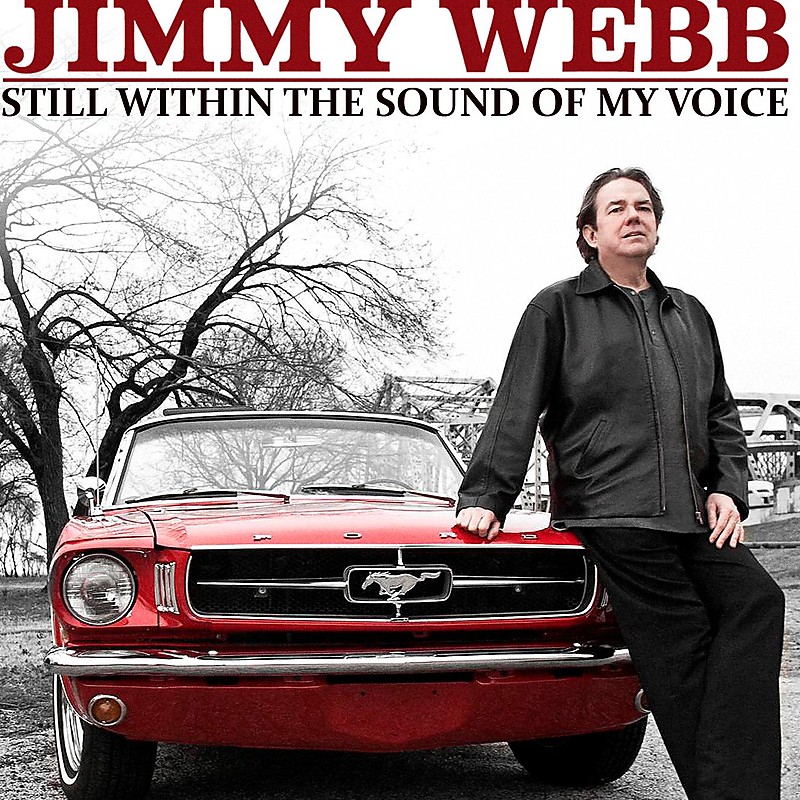

Webb was 21, the same age his now-good friend and sometime chauffeur, “Young John,” was when they met in 2009; they’re now arranging an October tour. In the last 15 years or so, Webb, who’s done film, stage and TV scores and produced albums for artists including Carly Simon and Art Garfunkel, has been spending more time on the road, particularly since releasing Just Across The River in 2010 and Still Within The Sound Of My Voice, its follow-up, this past October. Both feature him performing his iconic and lesser-known tunes with a variety of equally iconic singers. On the new one, Brian Wilson contributes backing vocals to a more subdued, nuanced “MacArthur Park”; Garfunkel sings “Shattered”; Amy Grant delivers “Adios”; David Crosby and Graham Nash share “If These Walls Could Speak.” Simon, Lyle Lovett, Marc Cohn, Joe Cocker, America, Keith Urban and younger voices Justin Currie and Rumer also contribute. Producer Fred Mollin suggested Kris Kristofferson for “Honey Come Back,” which, Webb says, Campbell always refused to do because he hated the talking interlude.

“With his acting ability, it’s magic,” Webb says of Kristofferson’s rendition. “Many little moments on these records are precious, and I’m glad we do ‘em. If we don’t ever make a dime off of them, I’m glad we did them.

“One of the coolest things we did was get the Jordanaires back together,” he continues. The backing vocalists for Elvis Presley, in their ’80s, sang on Webb’s “Elvis And Me.”

“The sound that we most associate with Elvis, that Jordanaires sound, we actually had the real thing in there, and that gives me chills,” Webb says. It was also the Jordanaires’ final performance. The last remaining original-era member, Gordon Stoker, died in March.

“There are so many acts out there today that are just cresting the hill and saying, ‘Well, so long, y’all,’” Webb says. “It’s kind of a sad time, but it’s also a great time to get some of these performances.”

Which brings us back around to the notion of being a legend. Johnson wants to see Webb’s signature etched among those in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame; for one thing, he says, “He’s the bridge between the Gershwins and rock and roll. He’s like the Hoagy Carmichael of rock and roll.”

Webb claims that it’s not awards, but hearing your songs in elevators and supermarkets, that confirms legendary status. Then he adds, “If you make records that stay fresh and people still enjoy listening to, I think that’s the stuff of legends.”

Fortunately, he’s nowhere near ready take that retiring-legend ride off into the sunset.

“I’m looking forward to making a new record of brand new songs,” he offers. “I’m very happy that Paul McCartney just put out an album of new music. Hopefully, he’ll pave the way for some of us aging singer-songwriters to go back to the lathe one more time. I know that I have songs in me that have never been heard … I really, really look forward to making another solo album. I’m a little bit burned out on ‘By The Time I Get To Phoenix’ right now.”

It’s true that an iconic song can become a mixed blessing, especially when an artist winds up “having to talk about it virtually every night of my life.”

Webb is nonetheless grateful at that the muses have been kind. His way of avoiding performance fatigue is to alter the songs with each delivery.

“I’ve seen him do ‘Wichita Lineman’ here at the Blue Door 12, 13 times, and never heard it the same way twice,” says Johnson. “And it’s not like he’s doing what Dylan did in those years when he completely changed the melody so you couldn’t recognize it. It’s just the endings might be different; there’s little nuances that are different here and there.”

Webb says not being tethered to a band gives him the freedom to change chord structures or other elements at will. And when he sits before a piano, his still boyish face reflected in its gleam, and unveils his soulful tenor, he literally can move listeners to tears.

For Webb, it all comes down to one essence. “My philosophy is that the song’s the thing,” he says. “I’m willing to do whatever I have to do to get from the beginning to the end, because I’m after an effect. When I wrote ‘I am a lineman for the county,’ I never worked for a lineman in my life. I had seen this guy on a telephone pole and I had been fascinated with what his life might be like. So there was a very natural curiosity combined with a very vivid image of this lonely figure on the top of a telephone pole speaking into a telephone, and just wondering who he was talking to and what he was talking about.”

But it’s how he spins those sights into musical metaphors that turn his songs into classics.

To young writers like Fullbright, Webb likes to impart, “If you’re gonna be a songwriter, then write songs. Don’t talk about writing them.” He also notes, “One of the things that I had to learn very early on that has held me in extremely good stead, is to ball up a song and throw it in the trash and write another one, and keep writing.”

Says Fullbright, “Jimmy Webb literally wrote the book. Those guys and gals went through a lot of shit before ‘singer-songwriter’ was even a term. We owe a lot to them.”

When Webb’s ready to pass the torch, he’s likely to hand it off to Fullbright, whom, he says, “I’m crazy about.”

“It’s a lot more fun to be an up-and-coming phenomenon of some kind,” adds Webb. “But being a legend is not so bad. I don’t think anybody should ever set out with that as a goal. That’s something that comes along when the time is right.

“If it is true,” he adds, “then I thank God for that honor, but it was certainly nothing I set out to do.

“I was just a kid in love with songwriting, and really, that’s what I still am.”

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.