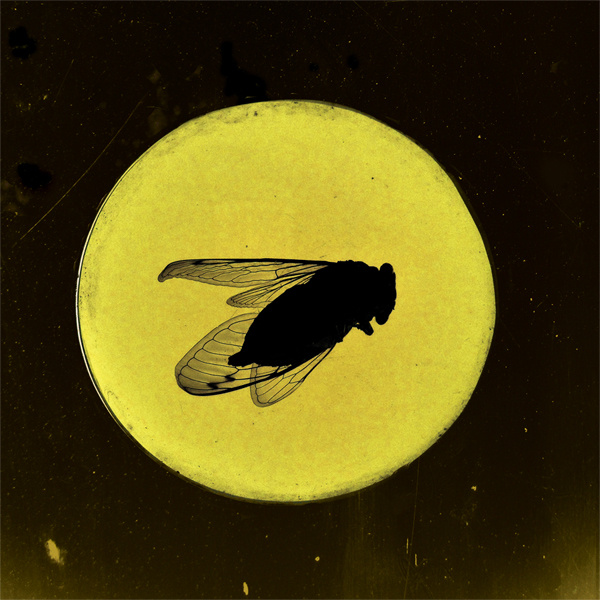

Honey Locust

The Great Southern Brood

(self-released)

3.5 out of 5 stars

Videos by American Songwriter

I’ve likely over-conceptualized Honey Locust’s first record, The Great Southern Brood, but it was easy to do. Named after Brood XIX, the geographically widest-reaching brood of cicadas that emerges once every 13 years, Nashville orchestral folk band Honey Locust’s debut full-length embraces a cyclical theme with an aesthetic and elegiac preoccupation with mortality and change.

In 2011, incidentally the same year the brood made its most recent appearance, Honey Locust broke into the scene with a plaintive brand of acoustic chamber folk that was over-styled in arrangement and understated in delivery. They were in a marginalized category in Nashville, which at least three years ago was trending on songwriting placed tertiary to sound and whoever could throw an opened PBR the furthest during a live show. And they also appeared to be outliers among the local folk artists who revert often heavy-handedly to traditional, minimalist Appalachian influence in lieu of detailed composition. Sort of the guy at the party who shows up in a tailcoat and stovepipe hat when everyone else has made some self-aware and blatantly shabby fashion choices.

Led by vocalist/guitarist/banjoist Jake Davis and composer/multi-instrumentalist Patrick Howell with a rotating group of backing musicians, the band released debut EP Fear is a Feeling in 2012, and if Fear was a sleepy, somber end-of-season effort skirting a cold, poetic sinkhole, The Great Southern Brood plunges into it with understated fervor and a fascination with death and the natural rhythm of things. Davis’ writing is interesting because while secretive, it is not cloyingly cryptic, relying on animals, seasonal imagery and nature for a tactile visual effect that balances the record’s abstractions that are like half-lucid daydreams; “Lantern In Your Nightmare” is one such intimation: “There are moments that I hold a little dearer/there were things unseen to me inside your mirror/there are many books about you, I have read some/once I tried to hold the lantern in your nightmare.” The themes aren’t heavy-handed, and in treading lightly on them Davis gives dimension to the idea of transience and the moribund.

Wrapped around the lyrical mire are layers of strings and horns that sensitize the listener to the restless, sometimes depressive cocktail of portents, curses and musings with a sort of storybook characteristic. Opening track “Wilderness,” a foreboding signifier of the record ahead, leads into “Honey Pot,” an ode to Honey Locust’s old house in Nashville where they lived for the first two years of the band’s existence. It’s plucky, wistful and whimsical, and as such is the album’s outlier, tracked live, which the band rarely does, at Ricky Skaggs’ Nashville studio. Each of the tracks has a vivid character – “Cherry Tree” is a macabre children’s folksong; “Blue Rooms” feels like purgatorial isolation – and between Howell’s lavish orchestration and Davis’ baritone, the record has a prestigious quality, almost overdone, that falls somewhere between visceral and cerebral.

Dark as the description may sound, The Great Southern Brood is not woebegone, but rather an impetus for speculation; listening to it is like a kid peering into a glass jar at a captured firefly. The record is discomforting, though, with a constant feeling of something impending and creeping ever closer that’s embodied by the record’s title track and thematic axis: “The Great Southern Brood is gonna be here soon/because the patient congregation has collectively awakened/from their earthly isolation/for the holy wide-eyed jubilee . . . Here for enough time to learn how to fly/and to re-sow the legacy under the ground/find a nice place to leave your skeleton.”

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.