To commemorate the 82nd birthday of the greatest and most important rock photographer of all time, we bring you the first part of our four-part tribute.

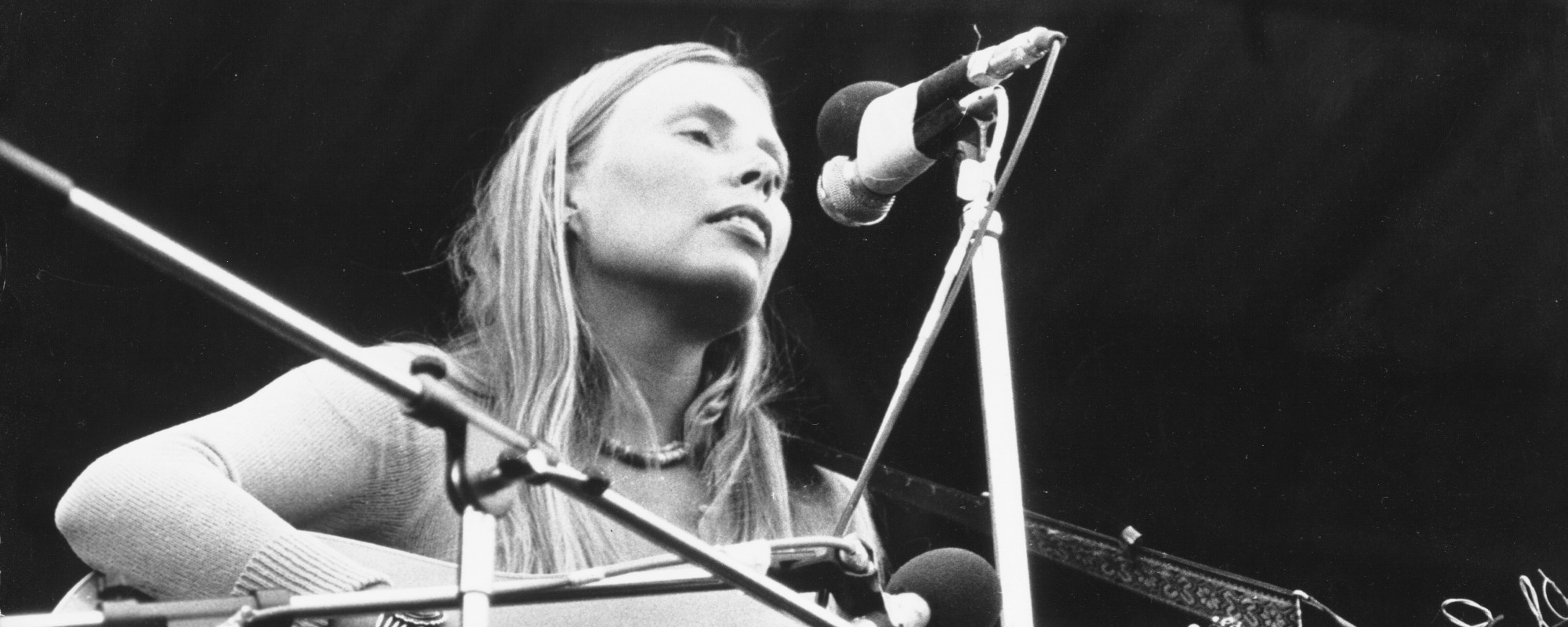

Part One of Henry’s historic journey from Kansas City to Munich to West Point to Woodstock and beyond, featuring the Modern Folk Quartet, Cass Elliot, The Monkees, Woodstock, Paul & Linda McCartney, Truman Capote, Jimi Hendrix, Phil Spector, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, The Doors, James Taylor, Joni Mitchell & more

Happy Henry Diltz Day! Today is the 82nd birthday, amazingly, of one of our favorite people ever, who also is Rock’s greatest and most beloved photographer. Although at this juncture, September 6, 2020, this day is still not recognized as an official holiday, oddly (even in California!), still we celebrate and invite you to join us.

Because he matters. To other photographers of music and fans, he’s much like the Buddha of the profession in many ways – the wisdom, whimsy, gentle joy and sense of universal love. (That is, if Buddha played banjo, which most scholars agree he didn’t.)

If you’re the kind of person who pores over the credits of classic albums, you already know the name. If you’re not, you’ve seen the pictures on the covers of albums by The Doors, CSN, James Taylor, The Eagles, Jackson Browne and thousands more.

His name is Henry Diltz. He was the official photographer of Woodstock and also for The Monkees even before he started creating iconic photographs for some of the most iconic albums of our times. He also happens to be, as many in the music industry have known for decades, one of this planet’s greatest people. As those who know and love him already know, he’s kind, sweet, funny, creative, generous, engaged, poetic, wise, curious, musical, bright, optimistic, romantic, compassionate and never boring. He’s also an extremely terrifying driver, but that’s fairly minor. (Except when driving with him).

Those iconic images which he’s taken grace the famous covers of more than 80 albums from the ’60s on, include James Taylor’s Sweet Baby James, the debut Crosby, Stills & Nash, Desperado by The Eagles, Jackson Browne’s debut and countless others.

He captured the famous photo of The Doors on their album Morrison Hotel by waiting for the surly clerk at this downtown fleabag hotel to vacate his post so the band could quickly run in and pose behind the front window. That effort and the image achieved has become also the namesake for the Morrison Hotel photo galleries he has here in L.A., New York and Maui.

Videos by American Songwriter

When I was a kid poring over album credits, I knew well the name Henry Diltz, as he was the photographer on so many albums by so many of our favorite songwriters and bands. His covers for Sweet Baby James by James Taylor, alongside his photo for the very first Crosby, Stills & Nash album (the one on the couch), together had such a tremendous impact, as did the great songwriting and music of both albums.

Because listening to those amazing songs, those voices, those harmonies – all of it – was matched by the experience of those photos. Because these weren’t the kind of staged, studio photos against backdrops that were common to album covers up to then. These were photos as real, organic and soulful as the music itself.

At the time, I made the wrong assumption that this Henry Diltz guy who took all the photos was no young man. It seemed that to be established as the photographer chosen to do all these landmark album cover photos would have taken many years. Which meant he belonged to our parent’s generation, although obviously much hipper than them.

The vision of him I had then was of a hip but old beatnik with a goatee, maybe a beret, and a camera. I figured he shot album covers for Sinatra, Nat King Cole, Judy Garland and the other icons of that era.

So that meant he had to be up there in age. I figured he was old – maybe 40 even!

I was wrong. He wasn’t an old beatnik, he was a young hippie. And a fellow musician. The reason his photos are so real and friendly is because they are photos of people looking into the eyes of a friend. And a very special, beloved and loving friend.

Before he started this photo journey, it was all about music for him. In addition to his photographic glory, he’s also a legendary musician, a singer who plays banjo, recorder, clarinet and guitar. He’s a founding member of the Modern Folk Quartet (MFQ), a famous folk group formed in Hawaii in 1961. He toured with them throughout the country in the early Sixties and recorded several albums, including the famous single “This Could Be The Night,” produced by the infamous Phil Spector.

Just to pass the time when on the road, Henry, along with his fellow musicians, bought cameras. But none of them took to it like Henry, a natural artist who delights in all forms of creative expression. He reveled in his newfound ability to create these little pictures, which he could then turn into slides and project to “blow the minds of my friends.”

And since many of his friends were famous musicians, he began to take some of the most beautifully intimate, natural and genuine photos of these people–which matched the intimate nature of their music much more than the former conventional studio glam approach.

And so by happy accident, and simply following his bliss, his music led him to become one of the leading photographers of his generation, part of a new school of celebrity portraiture which forever changed the visuals attached to pop music as profoundly as these musicians, his subjects, were changing the shape of pop music.

Born on September 6 in Kansas City, Missouri in 1938, his father was a pilot for TWA, and his mother a stewardess, so the family was constantly on the move. In WWII, his dad joined the Army Air Corp, and as a kid Henry was a typical army brat, living in different regions every year, from Florida to Alabama, New York, Japan, and beyond.

In 1944, his father died in a plane crash while testing a B-29 over Utah. His mother remarried a man named Duke, and Henry–known then as Tad–became Tad Duke. A few years later he became Henry Diltz again.

He studied psychology at University of Maryland in Munich, Germany. While there he heard about West Point.

“Someone told me that children of deceased soldiers could attend West Point for free,” he said on a sunny Saturday morning in his North Hollywood home. “It’s very hard to get into West Point. So I figured I should apply. So many people told me what a special rare opportunity it was, I figured I should go there.”

So this man who would come to visually define hippies for the rest of the world, as well as becoming one, attended West Point and became a cadet. And he adored it.

“I loved West Point. I loved the military trip of it, the pomp and circumstance,” he said. “It was a fun game and I was good at it. It put me in great shape. I played 22 different sports there. And I loved the parades, when you put on the starched white pants, and the cross-belts with a brass plate in the middle. You had to polish that brass plate to get it beautifully shining.

“I loved to march with the rifle and the bayonet and the big hat and gold buttons. You stand out in the field at sundown and they’d play the Star Spangled Banner and shoot cannons over the Hudson River. I loved that long gray line and the sound of the cannons boom and looking down the line and seeing all those breast-plates shining in the sun.”

But as much as these martial rituals satisfied him, he still hungered more than anything to play music. His love of folk music, of Pete Seeger and Bob Gibson primarily, both of whom played banjo, led him to want to make his own music.

So upon graduation, he headed straight to Greenwich Village, where he purchased his first banjo. Like getting his first camera, it would change his life.

To further his studies, he decided to go, banjo in hand, to the University of Hawaii. “I wanted to go somewhere far away,” he said, “because I had gone to college in Munich, Germany. So I liked the idea of Hawaii.”

Almost immediately upon arrival, as new friends recognized his musical aspirations, they all gave him the same name: Cyrus Faryar. A musician-poet and owner of the legendary Greensleeves Coffeehouse in Waikiki, he soon was Henry’s best friend.

This photo was the one chosen by Henry out of about 100 shots taken there, on the front lawn of his North Hollywood home in front of his famous and oft-photographed tree, with Joshua Zollo, my son there, and Cindy Bandula Yates, dear friend of Henry. I used Henry’s camera, his long zoom lens and shot it from a distance, entirely at his direction, to capture his exact vision. Still I take photo credit as if it was all my doing, which it wasn’t. Taking full photo credit for this isn’t exactly accurate, which is why there is no pressing need for one here, even knowing that many people notice the credit at the bottom of an overlong paragraph and little else. Photo by Paul Zollo/American Songwriter.

Cyrus had a magnetic charm which drew in artists, musicians and other Bohemian types. One such type was the late, great songwriter-author-cartoonist and womanizer, Shel Silverstein. He was the first to immortalize Cyrus, who was half-Persian and half-Welsh, in song, as Henry remembered: “It was called ‘An Arab’s Got a Right To Sing The Blues.’ It had one line: ‘And I can’t ride my camel into bathrooms with enamel/ An Arab’s got a right to sing the blues.’”

Singing at Greensleeves and other venues, little groups formed, and in this way the Modern Folk Quartet came to be, with Henry and Cyrus plus Jerry Yester and Chip Douglas.

In 1962 they left Hawaii to come to Hollywood and make their fortune. They were signed almost immediately to Warner Bros, and joined the momentum of the folk boom then booming.

Between 1963 and 1966, the MFQ recorded several albums, and toured all around America, playing often at the venerable Village Gate in Manhattan, where they opened for comedians such as Bill Cosby and Woody Allen. These were still pre-hippie times, and though the MFQ sang folk music, they dressed in suits. “We were sophisticated folk music,” he said with a laugh. “We had sophisticated chords.”

Phil Spector, then looking for a good folk-rock group to produce, discovered the MFQ, and began to groom them for a studio project.

“For a whole summer we’d go to his house, sit around a piano and sing,” said Henry. “He’d tell us each what to sing. And we’d sit and play our guitars and banjos, and he’d play his 12-string. Once we were playing The Trip (a club on the Sunset Strip) and he came in with his 12-string, sat on a stool, and performed ‘Spanish Harlem’ and we supported him.”

“At the end of that summer he said he found the perfect song for us. We went into Gold Star Studios (in West Hollywood) with the ‘wall of sound. (The “wall of sound” refers to Spector’s studio style of using huge bands and many singers to create a hugely full sound.)

“We did the track in one day, and then the next day we did the singing. During the playback, Brian Wilson was there in the control room, in his robe and slippers, and he’d just listen to it over and over and over. We could see him through the glass, but we didn’t go in there. We were in awe. He was our hero. He loved that song. Whenever he sits down at a piano to play, to this day, he always plays that song.”

Phil Spector also used Henry on banjo in other ‘wall of sound’ productions, including Ike & Tina Turner’s classic “River Deep Mountain High.”

“There were like eight guitar players,” he recalled, “six drummers, and me on banjo. Several drummers, always Hal Blaine. Big African hair drums. Tambourines, shakers, percussion people. One time I sat down and I was next to [guitar legend] Barnie Kessel.

“The songs had impossible chords I didn’t know on banjo. But Phil would hire Jerry Yester too, and he could play all those chords on guitar and would figure them out for me, how to do them on banjo. I’d play these arpeggio parts, these flowing parts like a waterfall, so sparkly.”

Although Spector was a functional and jovial man back then, he refused to release any record that he wasn’t sure would reach Number One on the Hit Parade, and so much to the profound dismay of the MFQ, decided not to release the record they figured could be the big hit they were waiting for.

Disillusioned, Cyrus decided to return to Hawaii, and the MFQ broke up for the first time. This was 1966. Chip Douglas joined the Turtles, Jerry Yester became a music producer, producing The Association and later Tom Waits and others, and Henry fell in love with photography.

Ten years later the MFQ reunited to make an album, and have since gotten together about every ten years to make a new one. Presently they have an album of Hawaiian music in the can soon to be released, and a Japanese tour on the horizon.)

Though Henry was soon to be a serious pro photographer, his love was entirely about art, and never with any intention of making money.

“I never thought of doing it professionally,” he said.”I just loved doing it! It was all about slide shows I’d give for my friends. I’d show these slides and blow my friends’ minds. And once you do that, you want to do it again and again!”

“It wasn’t really like photography, even. It was like a little visual game. I wanted to get the picture to sing, to get the wow effect.”

But his love for capturing vivid visuals was infectious, and his friends wanted to see themselves in those great slide-shows. They also recognized that Henry, a friend and fellow musician who shared their love of smoking “God’s herb,” as Henry calls it, was a whole lot more fun to be photographed by the pro photographers they’d known. It was Henry’s warmth and charm, as much as his technical and artistic prowess with a camera, that led him to become one of the great photographers of the Rock era.

When Neil Young and Stephen Stills, then in Buffalo Springfield, asked him to come along to Redondo Beach one day to shoot some stills, Henry took the first of what became an unprecedented chain of amazing photographs, many of which were used for the covers and inside sleeves of classic albums.

His first professional assignment was for his friend John Sebastian’s band The Loving Spoonful. They paid for him to come to New York, and he happily spent a summer taking photos of them. Because he was a friend of these famous folks, his photos were natural, unforced, and a great antidote to the fake studio glam then often foisted upon musicians.

Henry teamed up with art director Gary Burdon, who was adept at designing album art, as well as keeping up a conversation with a subject while Henry snapped away.

“Gary, who was even more of friend to everyone, made these shoots happen,” Henry said, always happy deflecting praise to others. “He was a very cool guy, he could talk to anyone”

When it’s suggested that description applies to him as well, he says, “Well, maybe now. But not then. I learned a lot from Gary.”

It was a formula that worked. Gary would maintain a genial atmosphere, and Henry would gently snap away. It’s a method that led to many famous photos of that legendary Lady of the Canyon, Joni Mitchell.

It’s a lesson that has served him well, as he has photographed many of the most famous people in the world. Henry was never an outsider; he always arrived as a fellow musician, one of the gang. “With famous people, you’re either a friend or a fan,” he explained.

For more information on Henry and his work: www.morrisonhotelgallery.com

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.