Videos by American Songwriter

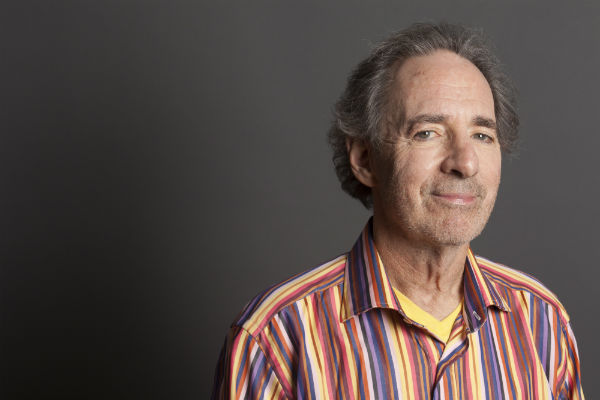

Harry Shearer is rarely himself. At least in public. He has reached a wide audience giving voices to characters like Ned Flanders and Mr. Burns on The Simpsons, as a sketch comedian on Saturday Night Live, and playing bass for The Folksmen from the film A Mighty Wind and faux rock gods Spinal Tap. The one place where Shearer can relax and be himself is on his weekly radio show, Le Show, on KCRW. Shearer is the host, interviewing guests from the world of entertainment and politics and writing satirical sketches and songs.

His four albums, including his latest, Can’t Take A Hint, are culled from the songs Shearer writes for Le Show. Shearer will react to a news story and write a song, and produce it quickly for air. Shearer made hint coming off of his Katrina documentary The Big Uneasy, hitting the studio with friends like Jane Lynch, Dr. John, Jamie Cullum, Jeff “Skunk” Baxter, and Fountains of Wayne. He also collaborated with his wife, singer/songwriter Judith Owen.

Shearer is on the attack for most of the album, taking down BP exec Tony Hayward, Samuel Wurzelbacher (better known as “Joe the Plumber”), Rupert Murdoch, pedophile priests, third world celebrity adoption, and everything that struck Shearer funny during a particular news cycle. He also includes two non-comedy songs, “Autumn In New Orleans” and “Cold Is To the Bone,” which may be the last time Shearer shows his serious side in his music.

We got behind the scenes with Shearer in this interview, an in-depth discussion of how he writes and produces music, how he approaches tragedy with comedy on songs like “Deaf Boys,” and how the more liberal-minded comic got along with guitarist Jeff Baxter, who has advised the U.S. government on missile defense.

How many of the songs have already appeared on Le Show?

I think every single one of these appeared on Le Show. That’s the only reason I would sit and write a song. Because I wasn’t intending to do another record, frankly. I move from area to area, not to sound too lachrymose, in the period where I’m licking the wounds from the last project. I’d done this documentary and gone on the road with it for a year and just thought, [shudders] what would be fun? Oh! Going into the studio with some musical friends. But I wouldn’t then sit down and write an album full of songs. But I’d already done that?

Are all of these the same version from the show?

No no no no no. What happens on the show is basically the equivalent of home demos. Then I take them to the producers I work with or the musicians I work with and say, well here’s the general idea, but let’s walk this upstairs, shall we?

I wanted to talk about one song in particular. I’ve heard a lot of songs that I’d consider evil –

I know where you’re going.

See if you can guess. I don’t think I’ve heard anything as evil as this particular track.

Yeah. “Deaf Boys?”

Yes.

Yeah. Yessir. When you’re dealing with a subject of astounding evil, let’s use that word because that was your word, I think it’s trivializing if the song doesn’t get to that level. If you’re going to write about that subject matter, you’d better be at that same intensity level as the subject matter or you really are trivializing.

The impetus for doing that song was, in the same week, a story came out about a now dead priest in Milwaukee who was found to have molested 200 deaf boys. And as I was absorbing that I saw a story literally that some week about a priest in Italy who had molested in the dozens of deaf boys, and a priest somewhere in England who had molested deaf boys. And I just thought, this is so bizarre that this is apparently a big thing that’s going on that we hadn’t heard about until now. And the number of the victims in the Milwaukee case just stayed with me.

So it led to that conclusion to do a “count up” song. There used to be a lot of them in the early days of rock and roll. There were more of them, at least. It was a style of songwriting. I think “99 and a Half Won’t Do” sort of started it. It seemed to write a song from inside the head of that heinous guy was the only way really to attack the thing head on and be grotesquely amusing about it. Not to pin any blame on Randy, but it was sort of Randy Newman’s approach to prejudice with “Short Prejudice.”

“Short People,” and you could look at “Rednecks” as well.

Yeah! “Rednecks” seemed, okay, I’ll buy that. It’s amazing to see Randy still doing “Rednecks” at this point in time with a word you can’t say anymore.

It’s got that fantastic turnaround at the end, too.

Yeah. Just to see a guy onstage singing that word unashamedly, because he’s singing it about a guy, and that’s the way that guy would say it. He wouldn’t say anything else. In for a penny, in for a pound. If you’re going to write about people like that, and you’re writing from inside their heads, you’re writing from their point of view, you’ve got to go there. And then having made that choice, the question was, how does he sound? I thought of singing priests and I immediately thought of Bing Crosby.

Ah, so that’s where it comes from.

Yeah, that’s where the style is from. It’s Bing. It’s Bing from Goin’ My Way and all that stuff. All those smiling, happy priests he played. And I tried some instrumental settings with it and I thought, those don’t work at all. Some sort of cross between Gregorian chant and doo wop would be the only real solution.

It might be the catchiest tune on the album, which makes it even worse for the subject matter.

[Laughs] Well, you know, I think sometimes… Let me put it this way. One never writes a song to be not catchy. Sometimes it works better than other times. If only for, you have to learn to sing it yourself, you know?

When you’re writing satirical songs, do you go with what comes to you, do you look at headlines to find things to write about, or do you go after the things that particularly irritate or anger you?

No, it’s stuff that I see that just rings a bell of some sort. With that one, it was that juxtaposition of stories and then the phrase “deaf boys” shone out of that collection of stories. It’s like, this is a new, horrific wrinkle on an already horrific story. And that phrase is singable and therefore suggested a song. “Celebrity booze endorser” was a phrase, I’d never heard that before. But it was in a Variety headline about Madonna signing to push a line of vodkas. I’m always on the lookout for occupations they didn’t tell us about on career day in high school. “Celebrity booze endorser” seemed to be at the top of the list.

Very often, it’s a phrase that will set it off for me. I don’t do research to write a song. It’s got to be something that I know something about that’s already kind of in my head, but then a phrase or a person will spark it. When they guy who was head of BP during the oil spill said, “I want my life back,” that was just, everybody sort of remembers hearing it, but that seemed to sum up a whole attitude of unconcern and narcissism in high-ranking individuals viewing the effects of their own misdeeds. So I put that guy in the position of this sort of sentimental, nostalgic tribute to the well that undid him seemed like an appropriate thing to do.

How do you choose the style of music to go with a specific topic?

Sometimes it comes from the character. “Like a Charity” is about a person that we know, so it was kind of basically done in an 80s style that she popularized. “Celebrity Booze Endorser” – it keeps sounding to me like a German name, Boozendorser, Boozedorser, German piano! – happened because I was listening to a Fountains of Wayne record in the car, then I saw that phrase. And when I decided to write the song, it was question of whether I was going to write it first person or third person. And because I had been influenced subconsciously by Fountains’ music, I wrote it as a third-person snarl at her. It seemed appropriate to do it in their style.

It really is the first thing, after I get the idea to do it, I have to figure that out because I have no style of my own obviously. I sit down and write lyrics. And I need to know the shape of the lyric, how long a line can be. So I really do have to conceptualize what musical environment the song lives in before I really can start working on it.

Does the point of view come first?

Yeah, point of view and then style. And then I can write the lyrics. And then I’ll sit down at the piano and try to find some chords that would be appropriate to that style that can be sung to. That sort of is the way it works for me.

Do you generally write on keyboard?

Yeah, I can’t play guitar. With the Sarah Palin song, “Bridge To Nowhere,” which sounds to me like her career at this point, just reminded me of that early 1950s sub-genre of lounge music called exotica. And since it was about this far away object, it seemed an appropriate style for her to be singing dreamily about the bridge.

Do you listen for particular instruments? If you write on keyboard, do you listen for that? And you play bass, obviously.

I listen to a lot of bass because I’m trying to learn how to play better. I’ll never be the kind of keyboard player that my wife is or people I know in New Orleans are. It’s basically just a utility instrument for me. I don’t listen to figure out better things to do on the piano. I practice enough that when I need to bop out a demo version of a song to be able to mash out some chords on it.

Do you have to be versed in all of these styles to get the nuances of them?

Yeah, it’s all junk that’s in my head. I’ve absorbed pretty much every piece of music I’ve ever listened to. It’s not abstract, if that’s what you mean. If I think about that, it brings to mind some sound, some world of chords, an idea of instrumentation. All of that sort of comes as a package when I imagine a style that’s appropriate.

Can the hooks get in the way of the message sometimes? If this hook works too well, does it distract from the message?

Oh, I don’t worry about that. First of all, I don’t have any idea how people hear these things or anything I do. I’m too busy putting myself in the head of the character to worry about putting myself in the head of the audience member, I guess. I think about 95% of the shit in show business is caused by people second-guessing the audience. Or trying to second guess the audience.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.