Videos by American Songwriter

Guy Clark’s house is tucked away off a main road in Nashville known to most for its Target, a conveyor-belt sushi restaurant and fast food chains. It’s not the prettiest part of town by any means, but once you take the turn, a bit past a gas station, you find a little enclave of mostly brick homes in an area that’s nicer than it ought to be, dictated by stop signs and little curvy roads. Down a short and steep little hill that I’m not sure my ancient hybrid car with cheap tires will have any luck getting back up, lies his home: modest, and obscured by a couple of trees leaking water from a passing rainstorm.

When I get there, Clark is waiting for me in the basement – though to call it that is to call a penthouse an attic. Not that it’s luxurious or decked-out by conventional standards, but it is a place full of enough musical relics to make your head spin: the walls covered in racks stacked with hand-labeled tapes and demos, notebooks, CDs, instruments, lyrics, tools and anything else that Clark has held on to over the years – he describes himself as a packrat of sorts, but it seems more archival than that. This is his workshop, where he used to make guitars (two at a time) before it got too painful for him to stand for hours on end. Joy Brogdon, his friend with Emmylou-Harris-silver hair and wearing a black Johnny Cash sweatshirt, leads me down the beige-carpeted stairs before offering me some coffee and disappearing again.

The Teachings Of Guy Clark

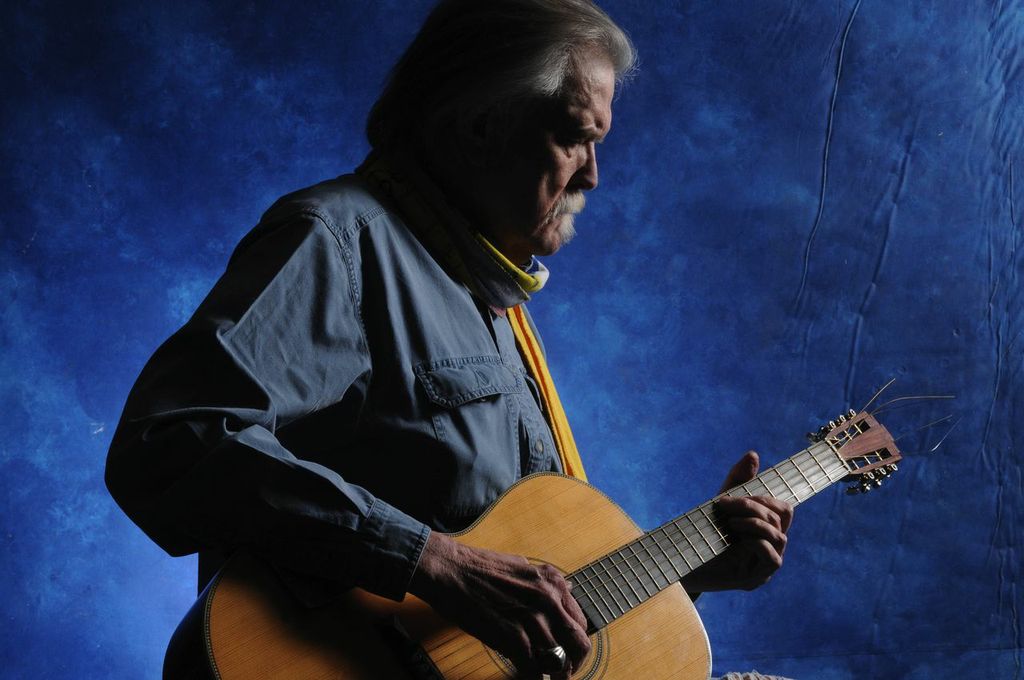

Clark, 71, is sitting at a wooden table in a denim shirt and jeans, which are torn and shredded at the knees like a pair Kurt Cobain might have owned – lighter in color than his iconic ensemble from the cover of Old No. 1, but denim just the same. In front of him is a tin of tobacco, a lighter, an ashtray, small scissors, a bag of what seems to be some kind of generic brand of cheese snacks and lots of scraps. His palms are resting on a pad of graph paper, with a few paragraphs written neatly on it in pencil. He lifts his hands to roll a cigarette, something he’ll continue to do throughout the remainder of my time here, snipping off the ends and relighting each again when they burn out.

“Ask me anything you want,” Clark says. “If I know it, I’ll tell you. If I don’t, I won’t.” He laughs, a hearty chuckle that is at once boyish and weathered; a laugh to tolerate the years, roughed by smoking and singing and cancer; by death and life.

It’s been a difficult year for the native Texan, but at the same time it has been a fruitful one. He finished his new 11-track record, My Favorite Picture Of You, the title song of which is about his longtime wife, Susanna, who passed away in 2012. The photograph, the one that Clark is holding on the cover art and also sings about, is of her, young, arms-crossed, looking angry and beautiful all at once.

“It was pinned on that wall right there,” he says of the Polaroid, pointing to a small space to my right. There’s a gap there, a toothless smile – he’s not sure where the photo is now. “It was always my favorite picture of Susanna because she was so pissed at me and Townes [Van Zandt]. We were just being drunk assholes, and she’d had enough … from the minute I saw it I said, ‘Yep, that’s Susanna.’ She was livid. It’s probably thirty years old.” He pauses to take a drag, a slow exhale. “But subsequently she died, so I don’t know if that made it better or worse,” he adds, laughing again, something he does frequently. He sighs frequently, too, deep ones that pull long and strong from his diaphragm and raise his chest up and down again, heavy and slow.

“Is this album a tribute to her?” I ask.

“Nah,” he says. “I just try to write the best songs I can, and they didn’t follow that theme. I never tried to write a thematic concept album. This one just happened uniquely, as much of them do.”

Watch Guy Clark Perform “My Favorite Picture Of You”

Like most of his work, the lyrics are a brilliant mix of imagery, prose and down-hard honesty. “The camera loves you / And so do I,” he sings, punctuating the last line with a spoken “click.” The production is bare, his voice softly matched to the cadence – it’s heart wrenching, really, mostly because it touches on truth, not manufactured moments or emotions. “I wrote the song about her while she was alive and I knew it was going to happen,” he says of her passing, and now he’s dreading having to relive those details in every upcoming interview. “That’s a lot of glue to unstick, you know. Forty years.” Still, he’d never think about removing the track from the record: good songs should be heard, shared.

Clark is a songwriter’s songwriter. Though she was talking about fiction, the author Jhumpi Lahiri once told the New Yorker that “everybody writes their first book with a certain innocence, a purity of vision,” and “the writer’s writer writes every book that way.” That is how Clark composes, how he lives: a purity of vision and constant quest for truth. Though he may not be a household name amongst the Spotify set, he’s often mentioned in the same breath with Bob Dylan, John Prine, Warren Zevon, even Woody Guthrie. With Van Zandt, of course, but even he has only been experiencing an uptick in pop-culture-trendiness in recent years, and still mostly amongst the Americana community. Yet these are the artists that drive the artists; and Clark is as true an example of this as it comes.

In a few days, he’s scheduled to receive an honor from the ACM awards, hosted by Luke Bryan. He’s getting the “Poets Award,” along with Hank Williams. Needless to say, he’s not going. “They sent me a very pointed letter which read, ‘You and Hank Williams are not required to be here.’ Well, ok, good!” It’s not too surprising that whoever wrote this letter isn’t aware that Williams might not actually be alive – this awards show, after all, features pyrotechnic versions of country where trucker hats trump cowboy boots and pop-infusions truly reign supreme. Bryan, who sings in a Kermit-the-Frog nasality and presents himself as a God-fearing fratboy, is the antithesis of anything close to Clark, who personally relates much more to the folk tradition than country – particularly modern country – anyhow.

“It’s like the Grammys,” he says, moving the can of tobacco closer. “I’ve been nominated for one five times. And every year I am nominated, so is Bob Dylan. I went a couple years, and I didn’t like it. Probably because I haven’t won. I’d be going back every year if I’d won.” He laughs. “Oh dear…”

Of course, for fans of Clark’s music, it seems quite strange that these accolades are few and far between – but it’s also what makes up part of his mystique. He’s been depicted as many things by the press: a “craftsman,” a master, a country original, a folk legend. In person, he comes off as a complete artist; a renaissance man in Western shirts. He reads (multiple books at once), he paints, he writes, he makes guitars. He has guilty pleasures, too – he likes television, particularly the Big Bang Theory, but mostly because he was a physics major in college. “Shit, I’ve gotten six or seven songs out of that show,” he says. He also likes the History Channel, and when I mention that he ought to try Breaking Bad, about a chemistry teacher turned methamphetamine impresario, he says, “Hmm. Meth makes me feel weird – too jangled.” He prefers really good cocaine, but hasn’t done it in ages.

Clark is the type of person that has taken inspiration from every moment in his life – every occurrence a meaning, a learning experience, something to build character on. Drugs, sadness, happiness, all of it. Even the graph paper has a raison d’être. “I used to be a draftsman for structural steel, and that was an influence,” he says. “But I’ve always enjoyed this kind of paper. I can always tell something I have written because no one else uses this stuff. Maybe it keeps my lines straight.”

“Guy Clark is always taking in everything that’s going on around him,” says longtime friend Lyle Lovett, whose song “Waltzing Fool” Clark covers on the new record. “He’s in a creative mode whether he is writing or painting, he’s in a creative mode when he is speaking to you. Just to be with him, to be in his presence, is a lesson first in humanity, but in art for sure. To be around Guy makes you want to be a better person, much less a better songwriter or painter or anything else. All that is just an extension of Guy.”

Lovett echoes a sentiment you’ll hear often when talking to admirers or peers of Clark: that he is a bearer of ultimate truth in song. They’ll often speak first about his character, and then about his art. “He’s upright, he’s forthright. He’s absolutely honest in terms of his take on the world and how he lives his life. He’s good through and through,” adds Lovett.

“He’s like my Ernest Hemingway in a lot of ways. Guy Clark taught me how to be a man,” says Justin Townes Earle, whose father Steve was a young disciple of Clark’s. “He taught me the beauty of simplicity, and to not be afraid to say something is beautiful, to say ‘I love you,’ to say your love for your wife or a woman or anything else.” He recalls being a young boy and hearing his mother play “Homegrown Tomatoes” around the house – Lily Hiatt, whose father is John Hiatt, also recalls a similar moment when she first fell in love with the straightforward humor in his lyrics.

“The first Guy album I remember listening to is Boats To Build,” she says. “My mother was playing it constantly … it started off with “Baton Rouge,” which made me giggle as a nine-year-old at the line about alligator shoes. I thought to myself, ‘This guy is funny, and he is warm.’”

It’s the dual ability of being able to write about food, shoes or instant coffee at the same time as composing songs like “Desperados Waiting For A Train,” “The Randall Knife” and “She Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” that gives Clark his incomparable footprint.

“I don’t think there are too many people that can write songs about homegrown tomatoes and rainbow pie and not sound like a cheese stick,” says Earle. “I think that guy has somehow found a way to explain those little things to us, and give them to us in a way where we don’t necessarily laugh.”

These days, and for this new record, he’s taken to co-writes to help find that voice or humor. “I used to write exclusively by myself, but I just got stuck,” Clark says. “I couldn’t write, and so I started co-writing with people I liked, friends of mine and bright young songwriters, and found I really enjoy it. There is something about sitting in a room with someone and committing.”

He collaborates frequently with younger writers like Shawn Camp, and is constantly looking to partner with more, well-known or not; and for both what they can offer him and what he can pass along. He co-wrote the title track for Ashley Monroe’s LP, Like A Rose, and Drake White, an up-and-coming Nashville singer-songwriter, recalls a recent session with Clark and Channing Wilson. “He’d sit there and be like, ‘nah, nah, nah,’ [as we were writing] and suddenly it was ‘yep.’ What I learned is that you don’t have to think outside of the box. You don’t have to do anything too quickly.”

“He’s so underrated. If you are a writer and you don’t know about Guy Clark then well …” White’s voice drifts off before he can finish the sentence. Trying to be polite, one can only guess, but you can imagine how that thought should end.

“I’ll try writing with anybody, just about,” Clark says. “Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. John Prine came over here and we sat for two days and all we got was ‘the train that couldn’t swim.’ We still talk about that. ‘Hey John, you finish that song?’”

Clark grew up in Monahans, Texas, with parents whom he describes as “very bright. We read poetry at dinner because there were no TV sets. We were always exposed to good literature or prose or poetry.” After an infamous detour to California that spawned the song “L.A. Freeway,” Clark moved to Nashville, which, in the ’70s, he describes as “like Paris in the ’20s.” He reconnected with the Texas crew – Van Zandt, Earle, Rodney Crowell, Billy Joe Shaver, a collective of artists not unlike what the Beat Generation was to New York in the fifties.

“Everyone was supportive,” says Clark. “I don’t know how supportive Picasso was to Ernest Hemingway … but it seemed like there was this really good sense of the work. Of just getting it done.”

Clark was best friends with Van Zandt for “four years,” and his wife Susanna, even closer – they used to talk every morning at 8:30 am on the telephone. At Van Zandt’s funeral, Susanna read a eulogy. “It was a moving little piece of writing,” Clark recalls. “She was talking about the fun they had, and how they’d talk every morning at that time. And the last line was ‘8:30 came, and the phone didn’t ring.’ Everybody was in tears. It still gets me.” It’s a story that Clark’s told before, but what isn’t as known is what happened in the moments following.

“After Guy made sure Susanna was okay, he came up on stage,” recalls the younger Earle. And he said, ‘Well, she wasn’t quite prepared for this. But me, I booked this gig thirty years ago.’ We all laughed. The room turned right back around.” Wit, levity and a pure sense of honesty about the inevitable – that was, and is, his gift. (Van Zandt, incidentally, “was so pissed that he outlived Hank Williams.”)

“People mention Guy and Townes a lot in the same breath, and they were certainly two sides of the same coin,” says Lovett. “Guy being poetic, too, but I always think of Guy as more prose-like and Townes being more poetry.”

Their interplay and dual nature even bred collaborations of a sort. “I’m always fixing someone’s songs, even Townes’. I changed ‘To Live Is To Fly,’ which Townes thought is the best song he ever wrote. He wanted to start with ‘you’re soft as glass and I’m a gentle man.’ Are you kidding me? I said, ‘man, what are you thinking? That shouldn’t start the song.’ He grumbled around, but he wound up agreeing with me. And even Steve Earle – he said I shouldn’t have changed Townes’ song like that. But it’s better! The silly shit …”

Clark takes the craft of writing as serious as ever – it is both a profession and a sacred art form. “It’s a really tough thing to get up every day and write, and come up with something that is really good work. And it doesn’t always happen. But some days, there it is. All you gotta do is have your pencil sharp. And a big eraser.”

There are tools he credits – first and foremost the habit of constantly writing everything down (a line he said to himself in the back of a car cruising down the highways of Los Angeles and scrawled in Susanna’s eyeliner on a paper bag became “L.A. Freeway”), discipline, pure inspiration, natural-born talent. Even drugs. “They can free you in a way from how you always think, or think straight. About getting the rent paid or the car fixed,” he says. “I don’t have anything against doing drugs and drinking and writing. I got a lot of songs I wrote under the influence, and I got a lot of songs I did really straight. It’s what you do with it. I’m not sure Shakespeare wasn’t taking methamphetamine all day, or something.”

He doesn’t use much these days – he likes “really good marijuana,” but quit drinking five or six years ago after he finished chemotherapy for Lymphoma and never got his taste for liquor back. He still keeps a nice bottle of tequila around the house, though, but is mostly relegated to cigarettes and coffee – when he gets up to refill his cup, he hands me a steel-string guitar that had been resting on a stand next to him. “Play this while I’m gone,” he says, and I sit there, paralyzed. I’m out of practice, not to mention intimidated: holding a guitar that Clark made, in his studio, that he regularly plays himself. When he returns I timidly ease out a couple of chords, and mention that I’d love to dedicate more time to learning the instrument.

“Well,” he laughs, “it’s good fun.”

I was supposed to leave an hour ago, but it’s okay, he assures me. His only commitment for the day is a visit from a Flamenco musician who is supposed to drop by in a bit, but “flamenco players are notoriously late.” Clark has a connection to the Spanish language – more specifically, to Mexico, garnered from growing up near the border in Texas. On My Favorite Picture Of You, there’s a song called “El Coyote,” about the men who smuggle immigrants into the United States, often to violent outcomes and for monetary gain. “I knew I needed to write that song,” he says. “I can’t get over man’s inhumanity.” Another track, “Heroes,” was composed as a reaction to the escalating number of suicides amongst veterans returning from the Middle East.

“It felt like something that needed to be addressed,” he says, but more importantly, it turned into a good song with a resonating chorus. “I want it to be something you want to hear again. And a lot of times, it’s not really a chorus, its just ‘desperados waiting for a train.’ And that’s all the chorus there is. Just that. Like how ‘my favorite picture of you’ is the only thing that repeats.”

Another standout is “The High Price Of Inspiration,” which charts both the emotional and technical costs of finding a muse: “inspiration with no strings, I’d like that even more,” is how the lyric goes, evoking “writing just for the money, or for the deal.” He sang this song in front of a group of music industry executives with as straight a face as they come.

“I really work hard at being true,” he says. “And that’s where the uniqueness of the songs come out. I couldn’t have made them up.”

Now, for the master of truth, there is one more difficult reality to face: his own future. As the talk shifts to performing, his heavy sighs begin to outweigh the laughs; there is little humor in his fears over not being able to continue as he’d like, to tour. A few years ago he broke his leg, and that, coupled with recovering from cancer, has taken its toll.

“I’m having a hard time playing and singing like I used to. I’m so crippled up, I walk with a cane, and I need someone to carry my bag and my guitar. So I’m just a broke down old songwriter,” he says. “I don’t have trouble getting gigs, but I will, because people are not going to pay to sit and watch me just be befuddled by what I do.” He looks down, still stuck in thought, clipping off the end of a cigarette but not relighting it just yet. “I’m really concerned about it. I’ll write, and I’ll continue to think about those songs being on another album but…” he takes a drag, followed by a deep breath. “So I guess we’re going to see what I’m made of.” Finally, he cracks a smile again.

We finish up talking, and on the way back up the stairs I notice a few things I hadn’t before – particularly the automated lift that Clark says he no longer has to use. He follows me with the help of a cane, albeit slowly. Brogdon has prepared some lunch for the two of them, and he sits down at his kitchen table, lowering himself carefully. I walk through the living room, past stacks of framed pictures of Van Zandt, posters, records, memorabilia of all kinds. The entire place feels very much alive; matched much more to Clark’s mental condition than to his physical one. But, bidding me goodbye, there is a sadness that cannot be denied from the man has “always tried to have a little ray of hope in the end result” of his music. That old time feelin’ rocks and spits, and cries.

“Guy is the kind of writer who is too strong to fade out,” says Hiatt. “His songs will remain long after he does. They get in your heart and mind, and they become a part of you.”

As I sit in my car, it has started to rain again, and my clothes, permeated with the scents of Clark’s workshop, have taken on the odor of burning tobacco. I repeat over and over in my head one of the last things Clark told me before we left the basement: “I always say, Look, I was trying to save my own life, not yours. If you get something from my songs, all right. Tell me what it is.’” I can’t let this go, because it’s the one time I think he was not being entirely truthful: Guy Clark has always been trying to save all of us with song, and always will.

Correction: In our article, we incorrectly stated that Clark was scheduled to receive an honor during this year’s ACM Awards. In fact, he is slated to receive the “Poet’s Award” at the ACM Honors in September. We regret the error.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.