The last few months of 2013 were busy ones for Rosanne Cash. In September, she previewed songs from The River and the Thread at a showcase in Nashville at the Americana Music Association Music Festival, where she also presented the award for Album of the Year at the Americana Honor and Awards show. On December 5-7, she completed a three-day residency at the Library of Congress that included a concert, a round robin with her husband John Leventhal, Rodney Crowell, Cory Chisel, and Amy Helm, and a conversation with U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Tretheway. Finally, in December the “music issue” of the Oxford American — this year devoted the music of Tennessee — hit the newsstands and featured Cash’s colorful narrative quilt in which she weaves threads of her memoir with threads of reflections on several of the songs from her new album.

Videos by American Songwriter

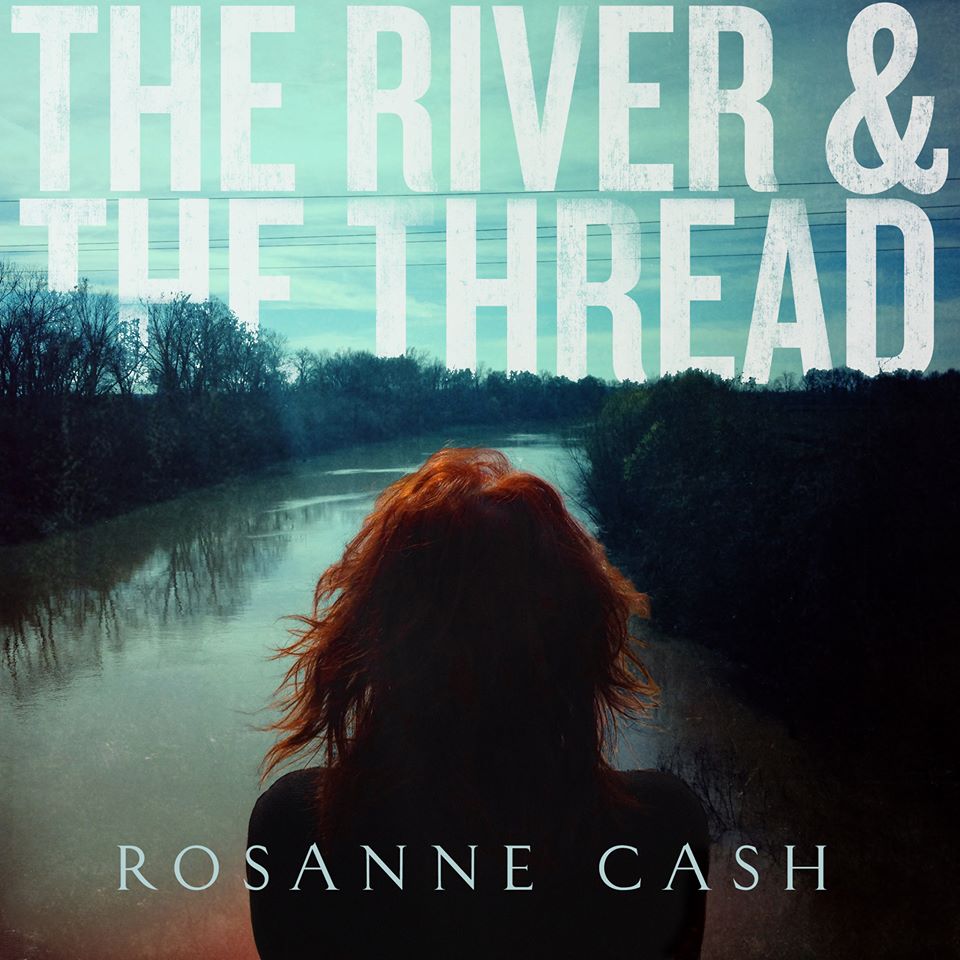

On her first album since The List (2009), Cash etches out a memorable musical journey through her past. She points out that when she and Leventhal, who also produced the album and played guitar on it, started thinking about the idea for this album, “It felt like it was going to be the third part of a trilogy—with Black Cadillac (2006) mapping out a territory of mourning and loss and then The List celebrating my family’s musical legacy. I feel this record ties past and present together through all those people and places in the South I knew and thought I had left behind.”

Joining Cash on this journey are an all-star cast, including Crowell, Chisel, Helm, Kris Kristofferson, Allison Moorer, John Prine, Derek Trucks, John Paul White, Gabe Witcher, and Tony Joe White. The music ranges from the swampy, funky shuffle of the opening tune, “A Feather’s not a Bird” and the gospel-inflected “50,000 Watts” (a song about Memphis radio station WDIA, which advertised itself as “50,000 Watts of good will”) to the rocking “Modern Radio,” which opens with a John Hiatt-like riff and to which her son Jake contributes background vocals, and the mournful and poignant ballad “When the Master Calls the Roll.”

In the blues and jazz inflected “The Long Way Home,” for example, Cash declares that “dark highways and country roads don’t scare you like they did,” as she weaves details of her family life into a song about the ways that the past haunts our lives. “Most of us go a long way and try a lot of things before we come home to ourselves,” she says. Other songs, such as “Sunken Lands,” provide details about her family’s life—the title of this song comes from the area where her father grew up in Arkansas—or details about the events that linger in our national psyche. “Money Road” takes its title from the grocery store where Emmett Till reportedly flirted with a white woman, leading to his murder.

Cash is so pleased with this new album that she says that “if I never make another album I will be content, because I made this one.”

American Songwriter caught up with Cash by phone recently at her home in New York City.

It’s been ten years now since your father died. What for you are his most memorable traits?

Kindness; he was a very kind man. I also loved the way his mind worked: idiosyncratic and expansive on all subjects. He encouraged you to be expansive, too, and find out all you could about whatever subject interested you. He taught me to think in a way that’s a little peculiar. What I really loved, though, was that he was propelled by rhythm, which was a great lesson in life and music.

What do you recall as your mother’s most memorable traits?

She was very disciplined. She had certain rules about social behavior, and manners were highly important to her. I’m really glad I got that from her. She created a wide circle of friends and created a life that really suited her.

What about June?

She lived a big life; what I loved about her was her performer’s instinct, which touched every aspect of her life, onstage and off. That instinct of hers influenced me deeply.

Who are your three greatest musical influences, outside of your own family?

I don’t know if I can name only three, there are so many whose music has shaped me. Bob Dylan’s album, Desire, and Ray Charles’ album, Modern Sounds in Country Music, were huge influences, and I love John Lennon, CSNY, Buffalo Springfield, and Janis Joplin. Joni Mitchell was probably my biggest musical influence because when I heard her it was the first time I realized that women could be singers and songwriters and could do it—and that I could do it—in a public way. And, you know, I loved Linda Ronstadt; in my early albums I was trying to re-create Heart Like a Wheel.

What about songwriting influences?

Lennon and McCartney gave me the basic structure and the subjects of those early Beatles songs were love. Later, Jackson Browne’s and J.D. Souther’s helped me expand on the basics and head into literary territory. When I was listening to Creedence Clearwater Revival and The Band, I realized: “Oh, you can write about subjects other than love.” Also, The Band’s songs were, for me, so cinematic, and I could see the stories the songs told. Rodney Crowell, Guy Clark, and Mickey Newbury opened my eyes to the discipline of songwriting. They created an ethic around songwriting. I set out to win their respect. We’d sit around playing songs, and I kept hoping that Guy would comment on one of my songs; he was mostly unresponsive until the moment when I first played “Seven Year Ache.” He kind of whipped his head around and asked me what song was that, and I told him it was one I’d just written.

Do you recall the first song you ever wrote?

When I was 18, I had gone on the road with Dad. I was trying to make my songs rhyme and trying to muddle through on the forms of songs I had inherited. Then, I wrote “This Has Happened Before”; I remember working so hard on that song and realizing that it didn’t have to fit all those forms I was trying to force on it; that was the moment that I felt like could do this.

What’s your approach to songwriting?

Well, it’s changed over the years. I work on songs in my head before I put pen to paper. Sometimes, I will write down 4-6 lines and then come back to them later. I think it’s wrong to take full credit for many songs, though. I feel like a lot of songs are already complete and there in the ether and you use whatever skills you can to pull them down. I do enjoy co-writing, especially with John. I’ve also co-written several songs by e-mail now, and it’s a great tool. Joe Henry and I wrote “Nothing but the Truth” that way. A lot of the songs on the new album are in the third person, and I put myself in those people’s place when I was writing the songs. I haven’t done that much before.

The new album track “When the Master Calls the Roll” has an interesting songwriting history.

Yes, I’ve never written a song quite like this. John and Rodney Crowell were writing a song for Emmylou Harris, but she ended up not recording it. I loved the melody, so I asked John if he thought it would be okay to ask Rodney if I could record the song. He said it couldn’t hurt to ask, so I did. Around the same time, our son, Jake, was working in his 8th-grade class on a project about the Civil War. I told Jake that he had ancestors who had fought for the Union in the Civil War, and when I searched a database on the Civil War, I found a photograph of William Cash. I’d always wanted to write a Civil War ballad, so I kept the first few lines that Rodney had written. One morning the last verse of the song came to me in a flood because it just hit me that Cash was going to die. I’ve never been that obsessed with a character before, and his death shook me so much I couldn’t stop crying.

How did you record this album?

It was sort of like putting a puzzle together. Sometimes we’d get in the studio and rewrite verses on the spot. Some of the time we did record live, but we did a lot of layering.

Where did the title of the new album come from?

It all started with Arkansas State University, really. They contacted me about their interest in purchasing my father’s boyhood home in Dyess, Arkansas. While John and I were helping with the purchase and renovation of the house, we made several extended trips through the South. We stopped at Rowan Oaks, Faulkner’s house in Oxford, Mississippi, since John is a real Faulkner scholar, Dockery Farms, the plantation where Howlin’ Wolf and Charley Patton worked and sang, and traveled the blues trail from Natchez. We also stopped off at Sun Studios in Memphis, and our son Jake got to strum a guitar in the same studio where my father cut his first record.

On these travels, my heart started cracking open to the South again. The sense of the ancient home that you carry with you is deep and powerful. Both John and I wanted to make a road record that revealed these deep connections. The album’s opening song, “A Feather’s not a Bird,” contains a line that I picked up from my friend, Natalie Chanin, who was teaching me to sew. She would say, ‘you have to learn to love the thread’, in that beautiful accent of hers. It hit me how powerful this image was, so I wove it into the song. The opening track is a mini-travelogue of the South and of the soul.

Your songs deal a good bit with loss, but they are often spiritually evocative.

You know, when I am writing, I don’t often think of this as loss, but I can interpret loss as longing. I think longing is what defines us human beings. Art awakens our senses and feelings to this longing. I appreciate your comment on spirituality. I think the spiritual terrain is deep and wide and that our longings often carry us to some of the place in this terrain. Art, music, and little children are the most spiritual—but not religious in the conventional sense—aspects of our world.

Have you come home with this album?

That’s a beautiful question. There’s part of me that’s always cared about the South and felt at home there. During these trips, as I said, the physical and geographical connections to place came alive again. The rich, beautiful, dense, and weird South is the South I love. Do you ever read that magazine Twisted South? (laughs) I love that magazine because it captures these aspects of the South. This new album explodes the stereotypes about the South and embraces them at the same time. You know, all these things happened that made me feel a deeper connection to the South that I ever had. We started finding these great stories, and the melodies that went with those experiences.

Who are your favorite Southern writers?

Oh, now that’s a hard question. Willa Cather, Charles McNair—I really love his writing—Walker Percy, Harper Lee, Truman Capote, and Walker Percy. Oh, and Charles Frazier and Mary Karr.

How have you grown as a songwriter, singer, and musician over the past 20 years?

Well, I’ve grown up as a songwriter. I started out singing about young love and the tortures of love. I look outside myself more and that creates more connections with others. I’ve become more connected to my own spirituality and am more in touch with that now. I think my songs have evolved poetically and melodically, and I’ve expanded in subject matter.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.