Videos by American Songwriter

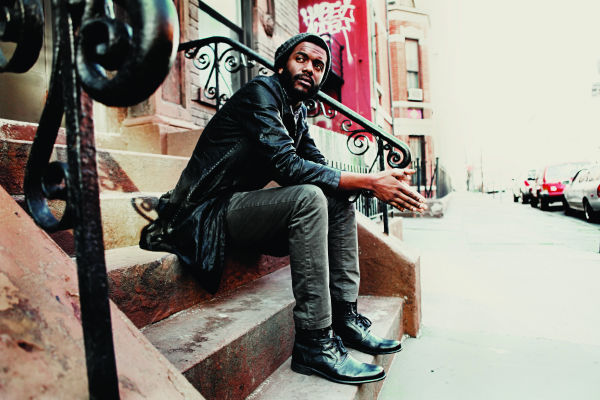

Gary Clark Jr. has been on a fast track since the release of his major label debut, Blak & Blu.

He’s a hard guy to pin down, moving from city to city for concert dates like Austin City Limits Festival and Neil Young’s Bridge School Benefit.

Finally on Election Day 2012, he’s in New York in the wake of Hurricane Sandy, to play three sold-out shows at Bowery Ballroom. The city is strained in the storm’s aftermath. “Driving in I could see … destruction,” Clark says on the phone from Brooklyn, where he’s added a last-minute relief benefit concert to support hurricane victims.

Clark calls New York his second home, though his roots are deeply Texan. He’s part of a direct line of the state’s now-revered bluesmen, from Blind Lemon Jefferson to Mance Lipscomb and Lightnin’ Hopkins.

As a teenager, Clark started hanging around the legendary Austin blues club Antone’s, whose owner, Clifford Antone, took a shine to the young guitarist. Antone’s was Stevie Ray Vaughan’s early stomping grounds and often showcased artists like Willie Nelson and B.B. King.

“That’s where I learned everything,” Clark says about Antone’s. “How to play, perform, and the history of blues music. I had a first hand take from guys like James Cotton and Hubert Sumlin.” Antone, who died in 2006, would invite Clark up to the stage, just as he had with Vaughn, to play side by side with the greats.

Blak & Blu’s opening track “Ain’t Messin ‘Round” is an update to the Texas blues canon in the vein of Albert Collins’ big-band rhythm and blues sound. The song features horns prominently in the intro, though the synthesizer-esque guitar riff could have been lifted from The Black Keys. “I don’t believe in competition/ Ain’t nobody else like me around,” sings Clark in a typical blues-braggadocio.

“Wake up in the morning, more bad news / Sometimes I feel I was born to lose,” Clark sings on the album’s second track, “When My Train Pulls In,” echoing Robert Johnson’s “Walking Blues” and Jimi Hendrix’s “Hear My Train A’ Comin’.”

Clark doesn’t offer anything as subversive as Hendrix’s last verse – “I’m gonna buy this town and put it all in my shoe / Might even give a piece to you” – but his tale has as deep of an effect.

And as its spellcheck-averse title suggests, Blak & Blu isn’t quite the “blues.” Clark mixes in elements of hard rock, electronic music, and hip-hop. “I got this reputation for being a blues guy, because I was always around the scene, I guess,” says Clark. But ever since his first recordings, he contends, “I was doing all kinds of things. Jazz, R&B … it was never, ever straight-ahead one thing.” Lately, he says, he’s been listening to the Swedish electronic band Little Dragon and jazz-soul legend Nina Simone.

Part of Clark’s gift is in dragging out dried-up blues memes and finding something fresh in them.

“Bright Lights” takes a nod from Indiana bluesman Jimmy Reed’s playful love lament and turns it into a prophesy of excess closer to Jay McInerney’s novel of the same name.

So the blues are just a starting point for Clark. But you have to know the rules before you can break them.

When Clark was asked to perform for the Obama White House’s “Red, White, and Blues” special on PBS, he chose two blues standards with deep histories: “Catfish Blues” and Leroy Carr’s “(In The Evening) When The Sun Goes Down.” The former, which Clark calls “a very important song,” can be traced to the obscure Delta musician Robert Petway, and also serves as the basis for Muddy Waters’ “Rollin’ Stone” and a later version by Jimi Hendrix.

On the White House stage, Clark is a vision of the past filtered through the present, and the President nods his head approvingly.

“[The blues] has been the foundation for a lot of stuff to come since. Guys like Muddy Waters, Robert Johnson, Chuck Berry, B.B. King. To be the new guy in that – to be included – was kind of a surreal moment,” says Clark about playing the show.

Before his performance, Clark says President Obama told him, “It’s really great what you’re doing – keeping the music alive.”

“I wasn’t expecting that,” Clark admits. “It was pretty heavy.”

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.