Country Music Hall of Fame member Bob McDill never envisioned himself as a country songwriter. A fan of folk music, his early songwriter inspirations included Joni Mitchell and Paul Simon.

Videos by American Songwriter

“They were great lyricists,” McDill tells American Songwriter of Mitchell and Simon. “Paul Simon, especially, had something to say. He painted beautiful pictures but he never preached. He never tried to tell you this should be your point of view. He just showed you the scene and you could make whatever you wished, same thing with Joni Mitchell and others.”

A Texas native, McDill had a unique journey to Nashville and country music. The revered songwriter’s childhood home was filled with song. He started viola lessons in the fourth grade while his mother often played piano. McDill fondly recalls sitting around the piano with his brother and mother on Sunday afternoons singing pop songs and hymns. By 14, he picked up the guitar, as detailed in his No. 1 song “Amanda,” recorded by Don Williams. I got my first guitar when I was 14, Williams sang on the 1973 track.

McDill also played in a skiffle group named The Newcomers around Beaumont, Texas. Shortly after he joined the trio he began to write songs. “I used to be pretty obnoxious with it, making my parents listen to each little snippet that I had just written when they were trying to watch Gunsmoke,” he says with a laugh. “I certainly put in my 10,000 hours.”

The Newcomers played several of the songs McDill wrote around town. Soon, producer Allen Reynolds and singer/songwriter Dickey Lee heard the tunes and became McDill’s earliest champions, signing him to a publishing deal. McDill continued to write songs when he joined the Navy. His first cut was “Happy Man,” recorded by Perry Como in 1968.

“The first chart record I had was by Perry Como when I was in the Navy,” McDill recalls. He says he learned the news when Reynolds and Lee wrote him a letter during his service. When he was discharged, McDill moved to Memphis to work with the pair alongside Jack Clement and Bill Hall.

By 1970, the burgeoning songwriter moved to Nashville with Reynolds, Lee, Clement, and Hall. McDill eventually signed to Clement and Hall’s publishing company. A couple years into his Nashville journey, McDill and Reynolds wrote a folk song titled “Catfish John.” The song took off on the country charts after Johnny Russell recorded it and peaked at No. 12 in 1973. According to the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, the song was about a “former enslaved person McDill’s father befriended as a boy.” Jerry Garcia, Alison Krauss, and Nitty Gritty Dirt Band would go on to perform or record the song. The success of “Catfish John” had McDill seeing the country genre differently.

“‘Catfish John’ became a country hit, which sort of taught me that, ‘Well, I can do this.’ So I began studying country music,” he says.

His studies paid off. McDill would see success again with Russell when the country singer recorded “Rednecks, White Socks and Blue Ribbon Beer,” which reached No. 1 in Canada. Williams, Keith Whitley (“Don’t Close Your Eyes”), Alabama (“Song of the South”), Pam Tillis (“All the Good Ones Are Gone”), and Alan Jackson (“Gone Country”) have also recorded and seen great success with McDill’s songs. Fittingly, in October 2023 the revered songwriter was formally inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame. He joined the esteemed class alongside Tanya Tucker and Patty Loveless and became the ninth non-performing songwriter inducted into the Hall.

During his induction speech, McDill listed off the master songwriters who were previously inducted in the Songwriter category: Dean Dillon, Fred Rose, Bobby Braddock, Don Schlitz, Cindy Walker, Harlan Howard, and Felice and Boudleaux Bryant. “We are a big part of the music business as a whole and should be recognized,” McDill says of the importance of songwriters being invited into the Hall of Fame.

Today, McDill’s timeless songs are revered within the country genre and by its songwriters. Although he retired from songwriting in 2000, his work ethic lives on with those who came after him. Fellow Country Music Hall of Famer Schlitz shared the advice his mentor gave him at the beginning of his career.

“For my friends and me, Bob McDill is who we wanted to be,” Schlitz said ahead of inducting McDill into the Country Music Hall of Fame. “He taught me mostly by example, but he also told me a few secrets that I still think about every day. He taught me we get 10 songs a year by inspiration. Our job is to write 40 more songs a year for the radio.”

McDill wrote songs every day from 9 to 5, and sometimes at home on Saturday and Sunday. One of those home inspirations was “Don’t Close Your Eyes.” The idea came from the 1978 film California Suite based on Neil Simon’s play of the same name. McDill was walking through the living room while his wife at the time and daughters were watching the movie. One of the storylines followed an actress who was nominated for an Oscar and whose husband was gay.

“She knows her husband is gay and she’s very depressed at the time and very upset because she didn’t get the Oscar,” McDill recalls of the film’s plot. “She tells him, ‘Hold me tonight and don’t close your eyes. Don’t dream of someone else.’ I thought, ‘Well, that doesn’t have to be about a gay relationship. It can be about any relationship.’ I took that little snippet and built on it. It took a long time to put that thing together. Simplicity is a difficult thing to achieve.”

McDill says that ideas can come from anywhere. “If you get desperate, you go to a bookstore and start looking through fiction titles,” he says.

Other song ideas can come from a simple conversation. The title for “All the Good Ones Are Gone,” which Tillis recorded and received a Grammy nomination for in 1998, came from hearing women say the phrase over the years.

“I had that title and I threw it at Dean [Dillon],” McDill recalls. “He came back right back with: She’ll turn 34 this weekend, she’ll go out with her girlfriends. We put it together in a few days. One of the girls in the office who typed lyrics and did copyrights, I walked by her office and she looked at me and said, ‘Hey, you just wrote my life.’ I knew it had something when she said that.”

McDill says he was “pretty relentless” as a songwriter. He didn’t give up on songs easily, and would sometimes work on a song for months. He learned his work ethic, in part, from being an admirer of the late novelist and poet Robert Penn Warren.

“He was a workaholic,” McDill notes. “One of his letters to a young person said, ‘If you burn out on this particular thing, this essay, then don’t go home. Turn the page and work on that poem that you couldn’t finish. If you burn out on that poem, turn the page and work on that novel that you’re trying to finish with fresh eyes each time.’ That’s the way I would approach it. If one thing wasn’t working, I’d turn the page and find something else that I put aside.”

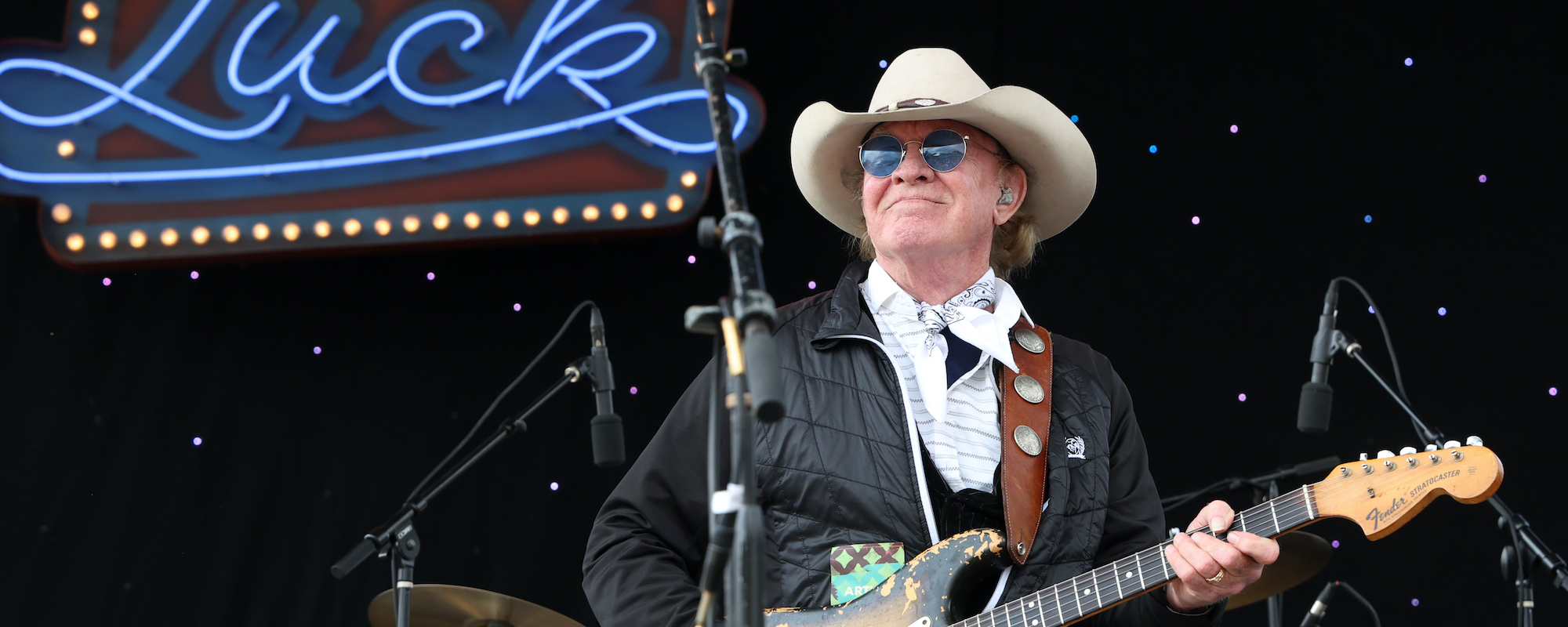

Photo by Terry Wyatt/Getty Images

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.