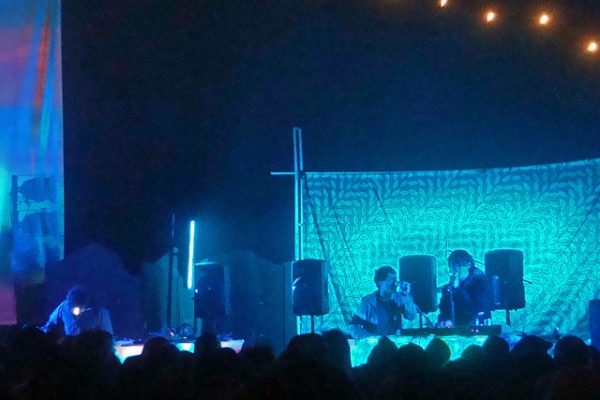

Animal Collective performing at the Henry Miller Library in Big Sur, California. Photo courtesy of ames sf.

Videos by American Songwriter

There’s an inherent irony when you think about the fact that the more that people sit in front of computers virtually connecting with each other, the more they will connect in the real world. But that’s exactly what Eventbrite co-founder and President Julia Hartz says is happening.

“Online behavior has only driven more offline experiences because you’re able to find each other online easier,” says Hartz. “Events are really the one thing you don’t think twice about sharing. You want your friends to come to events and you want to go to events that your friends are attending.”

Eventbrite, a self-service ticketing platform that was founded by Hartz, her husband CEO Kevin Hartz, and CTO Renaud Visage, makes the connection between real-life events and the virtual world even easier.

In 2006, Eventbrite’s founders were looking at payment processing platforms and saw an opportunity in event ticketing.

“What intrigued us about the event space [was that] people were not using any technology to sell tickets,” says Hartz. “They were using excel spreadsheet and email and paper invites and collecting cash or checks at the door.”

Hartz says the world of ticketing in 2006 looked especially “disruptible” to her and the company’s other founders. “The entire industry as a whole really lacked innovation,” she says.

So the nascent Eventbrite team began building tools for event organizers and the new platform quickly caught on with the tech community, especially in and around Silicon Valley and San Francisco, where the company is based.

Interestingly, though, while Eventbrite saw itself as a niche within the larger ticketing business, it never identified itself solely with one niche or market of events. It would prove to be a wise decision as their easy-to-use platform was adopted by a myriad group of event organizers.

“We let whatever type of event wants to [flourish], flourish on Eventbrite,” says Hartz. “It’s a self-service platform. We discovered new verticals ourselves,” she says referring to the company’s “agnostic” approach to vertical markets.

In late 2007 and early 2008, Hartz says Eventbrite went viral and their team started noticing that event attendees were turning into event organizers. The next step for Eventbrite was nurturing their community and aiding in new discovery and a key solution was found in aligning Eventbrite with Facebook. Hartz says users were already taking their event details from Eventbrite and adding a Facebook event, then linking back to Eventbrite to sell tickets. So Eventbrite embraced it.

“We became the first events API user for Facebook Connect and created a one button push,” Hartz says. Integrating Facebook Likes also helped promote sharing on the site and in 2010 Facebook surpassed Google as the number one traffic driver to Eventbrite.com.

Hartz says that while Eventbrite has worked with events ranging from a three-person yoga workshop to a 75,000 person political rally, one of the company’s fastest-growing verticals over the last few years has been music.

“We’ve always loved music,” says Hartz, “[but] we haven’t treated it in a different way than [any other vertical market].”

While the live music ticketing space remains as complicated as ever, Eventbrite has caught on with smart promoters like California-based (((folkYEAH!))), which promotes concerts in unique places like the Henry Miller Library in Big Sur and the The New Parrish in Oakland, California.

Hartz says Eventbrite offers an openness and transparency. “It allows promoters and artists to feel like they have freedom to make Eventbrite whatever they want it to be,” she says.

But, true to form, Eventbrite has let promoters and venues discover the service on their own. Hartz says they had little warning when tickets went on sale through Eventbrite for an Arcade Fire show at the Henry Miller Library.

Hartz says that while Eventbrite isn’t currently the best solution for small and medium-sized music venues – for one, they don’t offer reserved seating – they are perfect for artists’ house shows as well as bigger, open festivals like Washington, D.C.’s Shamrock Festival, for which Eventbrite can handle large volumes of ticket sales.

“We’re not going after Ticketmaster’s customers right now because we can’t service them. We know our own limitations,” admits Hartz.

Where Eventbrite may gain traction in the murky relationship between venues and ticketing vendors like Ticketmaster, Ticketweb, Ticketfly, and eTix, is if the industry opens up to allow for a hybrid allocation ticketing model, whereby fans would have the option to purchase tickets from more than just one ticket vendor.

“We’ve had customers who have used different vendors in addition to their current vendor and we’ve been one of them. It’s a great place to be able to show our capability and creates competition among ticketing services,” says Hartz.

For a service that clearly understands the customer and is bringing innovation to an industry that has changed little for decades, Eventbrite’s future in music looks very promising.

“By the time we’re ready to handle stadium concerts and big venues and reserved seating there will be a place for us to come in and be friendly disruptors in that space,” says Hartz.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.