Videos by American Songwriter

In January, an insider “earwitness” told the Hollywood Reporter that Bruce Springsteen’s forthcoming album Wrecking Ball will represent the 62-year old’s “angriest yet.” Since history has found Springsteen at his most vitriolic when writing from headlines, it seems safe to assume that album 17 will find the Boss in topical-mode. His exact targets, however, remain a mystery. Contrary to initial speculation, the record was completed months before the Occupy movement started gaining traction.

If the Reporter’s source is accurate (lead single “We Take Care of Our Own” struck us as more anthemic than angsty), Springsteen will join a veritable demolition crew of American artists who have carved frustrated statements out of albums and songs entitled “Wrecking Ball.”

It’s a tradition that began in 1995, when country legend Emmylou Harris employed the title on an album that would signify a major turning point in her career. Partly inspired by the singer’s growing estrangement from mainstream country, Harris underwent a stylistic deconstruction on Wrecking Ball— making her application of the term a decidedly literal one.

The mid-nineties marked a rough period for country’s elder stateswomen. A new breed of cowgirl had arrived. Bubbly, easygoing, free-spirited: these firebrands bore little resemblance to their introspective and comparatively dignified predecessors. Furthermore, America’s regrettable obsession with line-dancing hit its peak during this time, leaving little room on country radio for the plaintive torch singers of yesteryear.

“It’s pretty obvious to me that I’m not going to be played on country radio, so why not just go to that other place that I’ve always been, anyway?” Harris told the Chicago Tribune around the time of Wrecking Ball’s release. “I’ve always had one foot in left field, so I just decided to plant the other one there.”

With the aid of producer Daniel Lanois and fellow country outsiders Steve Earle and Lucinda Williams, Harris crafted an atmospheric, reverb-laden masterpiece that would eventually net a Grammy for Best Contemporary Folk Album. Characterized by its dreamy tone and murky textures, Wrecking Ball sounded unlike anything else emerging from Nashville at the time. Today, the record is widely regarded as a high-water mark for modern country and has impacted artists ranging from My Morning Jacket to Neko Case.

* * * *

One of the highlights on Harris’ Wrecking Ball is “Orphan Girl,” a track penned by an aspiring West Coast folksinger named Gillian Welch. Seven years after the release of Harris’ record, a newly established Welch would end her 2003 album, Soul Journey, with an autobiographical tune also titled “Wrecking Ball.”

The song’s lyrics offer a chronological account of Welch’s formative years, with emphasis placed on very minor details. We learn that she played bass under a pseudonym as a teen, attended college on a scholarship and drank a Jack and Coke one morning in San Joaquin.

The inclusion of all of this minutia helps paint a vivid self-portrait of Welch. Though sonically, it’s the most “un-Welch” thing the singer has ever produced. The song is a driving, electric rocker– miles divorced from the delicate, Appalachian lullabies that made her a Starbucks fixture.

Like Bob Dylan and Uncle Tupelo before her, Welch was deemed “inauthentic” early in her career by critics who found the Los Angeles native’s rural themes and rustic stylings disingenuous. In a review of her 1998 album, Hell Among the Yearlings, City Pages’ Chris Herrington remarked, “Welch is someone who discovered old-time music in college and decided that her own sheltered life could never be worth writing about.”

“Wrecking Ball” is Welch’s reaction to Herrington: a rollicking, new-time song in which she describes her “sheltered life” with arduous detail.

* * * *

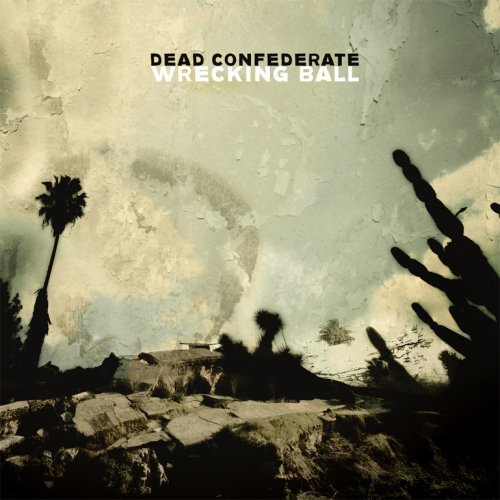

Just as critics were overeager in discrediting Welch, they were a tad premature in declaring Athens’ Dead Confederate a “next big thing.” Wrecking Ball, the band’s 2008 debut, was hailed by the A.V. Club’s Chris Mincher as the birth of an exciting new sub-genre that merged alternative country with grunge. (Obviously, the album has yet to spark the crossover trend Mincher predicted.)

It’s worth noting, however, that a germ of this hybrid can be found on Neil Young’s similarly titled 1995 collaboration with Pearl Jam, Mirror Ball. Also worth noting: Young wrote the title track for Harris’ Wrecking Ball (released the same year).

While Dead Confederate’s alt-country leanings were audible in flourishes, the band seemed far more interested in kickstarting a grunge revival on their debut. The record boasted an abundance of genre signifiers, from sludgy riffs and shapeless solos to frontman Hardy Morris’ strained, warbled yelps.

Since Harris, Welch and (allegedly) Springsteen attached the title to reactive works, Dead Confederate’s contribution to the Wrecking Ball cannon might feel comparatively slight and disconnected. But consider this: out of all the bygone movements the band could have attempted to resurrect, they picked the unfashionable one that was virtually synonymous with teenage frustration and angst.

A lot of pressure gets put on burgeoning young “it” bands to make their first effort a mission statement. Dead Confederate, however, didn’t really have all that much to state. The group started out as a jam band, arguably rock and roll’s most unambitious animal, so it kind of makes sense that they would look to grunge for inspiration. It was, after all, Generation X’s rally call to a population of complacent and unambitious youth.

Make no mistake, there’s as much tension and frustration underlying Dead Confederate’s songs as any of the aforementioned artists’– it’s just coming from a slightly different place. Tension and frustration are attributes inherent to grunge, making the band’s disposition a byproduct of their influences instead of their experiences.

In a way, that makes the group’s angst a sort of genetic malfunction: a condition every single one of us can relate to. While we haven’t all been exiled from country radio or called inauthentic by rock critics, we’ve all felt frustrated for no obvious reason. Like Springsteen, sometimes our exact targets remain a mystery.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.