Videos by American Songwriter

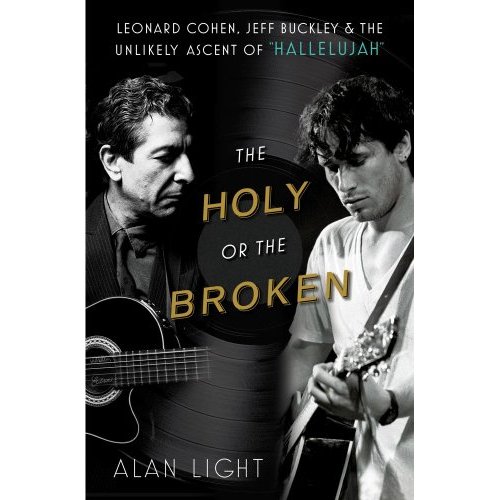

Alan Light’s The Holy or the Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley and the Unlikely Ascent of “Hallelujah” explores how a random album track on Jeff Buckley’s commercial flop Grace— written by an old master, Leonard Cohen — went on to change the course of music history. The book is available December 4 from Atria Books. Read our exclusive excerpt below.

* * * * *

Jeff Buckley’s Grace album was released by Columbia Records in August 1994, amid a flurry of hype. The final song selection included seven songs written or cowritten by Buckley; three of his wide range of covers also made the cut, illustrating his sprawling tastes and influences. The album’s fourth track is Nina Simone’s “Lilac Wine,” a staple of his live show. A version of Benjamin Britten’s “Corpus Christi Carol” comes near the record’s end. Right at the album’s center sits “Hallelujah,” the set’s longest track.

For all the high expectations, though, and the mystique it would later acquire, Grace was a flop; it didn’t make the Top 100 on the U.S. charts, and only one single, “Last Goodbye,” made any kind of dent on rock radio. (Buckley did, however, make the list of People magazine’s 50 Most Beautiful People in 1995.) Like Leonard Cohen before him, Buckley made more of an impact overseas: Grace nicked the Top 50 of the charts in the UK and France.

Even within the limited attention that the album did receive, “Hallelujah” was far from being the focal point. Four songs were eventually released as singles from Grace (the title track, “Last Goodbye,” “So Real,” and “Eternal Life”); there was actually talk of releasing “Hallelujah” as yet another single, but by that time, sales had slowed to the point where Columbia decided instead to drop its promotional efforts. Feature stories and interviews with Buckley hardly mentioned the song, and its reception by the critics was mixed.

In Rolling Stone, Stephanie Zacharek wrote that “the young Buckley’s vocals don’t always stand up: He doesn’t sound battered or desperate enough to carry off Leonard Cohen’s ‘Hallelujah.’ ” A year-end wrap-up in the New York Times offered a different perspective, though. Stephen Holden (who had covered the St. Ann’s show for the newspaper) wrote that the recording “may be the single most powerful performance of a Cohen song outside of Mr. Cohen’s own versions.”

Some reviews for Grace were downright negative: The influential “dean of American rock critics,” Robert Christgau, listed the album in his 1994 “Turkey Shoot” in the Village Voice, writing, “It’s wrong to peg him as the unwelcome ghost of his overwrought dad. Young Jeff is a syncretic asshole. … Let us pray the force of hype blows him all the way to Uranus.” But, despite its commercial failure, when the smoke cleared, Grace appeared on many critics’ lists of the year’s best albums in the U.S., the UK, and France.

More significantly, Jeff Buckley was celebrated by the rock and roll elite: Paul McCartney, Jimmy Page, Elvis Costello, and Eddie Vedder were among the stars who raved about the young singer. If he didn’t quite turn into the pop star he was supposed to be, Buckley was at least a top-shelf underground celebrity. And among young listeners, especially those who were dreaming about making music themselves, “Hallelujah” was a song that was attracting some notice.

Almost a decade before her debut, Come Away with Me, sold ten million copies and won five Grammy Awards, Norah Jones stumbled across Grace as a high school student in Texas. “I went to the CD store, it was on display and it looked interesting,” she said. “But I remember thinking, ‘Is this a Christian album? It’s called Grace, it has songs called “Hallelujah” and “Corpus Christi Carol” on it—that’s not what I came here to buy.’ But I listened to a little and it sounded kind of cool. This was when it first came out, and nobody really knew about it—hey, does that make me cool?”

She soon discovered “Hallelujah,” and couldn’t stop listening to it; in 2012, it was her answer in the category “First Song That I Was Obsessed With” in an interview with Entertainment Weekly. “It’s just stunning, it’s one of the most beautiful things ever recorded,” she said. “I believe every word he says. I had a boom box with a CD player and a repeat button, and I’d play it over and over. I’d fall asleep to it, but when he hits that high note, every time it would wake me up, so I’d wake up every four minutes.”

For Brandi Carlile, growing up in Washington State, the religious overtones of the song had a more specific resonance. “It was really the song from Grace that most jumped out,” she said, during a conversation in her Manhattan hotel room, a few hours before a sold-out show at Town Hall. “Somebody played that song for me and I fell head over heels in love with it. I was having really complicated faith struggles during that time. I just had an instant connection to it based on that.”

So there was the substance of the song, and for some listeners, that was the key. But there was also that indescribable essence that Buckley was trying to conjure in take after take during the sessions. The fans that reacted so strongly to this song were connecting directly with Jeff Buckley, to an intangible intimacy that certain recordings convey and a clarity that he seized on and never let go.

“A lot of musicians talk about it, but there really is something to a magic performance—it’s a rare thing,” said Patrick Stump of the pop-punk band Fall Out Boy, who would later incorporate part of “Hallelujah” into a song of their own titled “Hum Hallelujah,” which would in turn become a favorite of their own fans. “The thing about the Jeff Buckley version of ‘Hallelujah’ that gave it another life was that it was just a magical performance. There really are very few of those in music history, recordings that are just dead-on—something like Otis Redding’s ‘These Arms of Mine.’

“Jeff Buckley had that quality, and even he couldn’t have performed the song that same way again. [Cohen’s] original was so produced, and Buckley’s is so small, just a guy and his guitar, and he makes it so personal. . . . He was able to find so many different things in that lyric—sex, passion, darkness, beauty are all in his voice. In the end it lends itself to Jeff Buckley’s legacy as much as Leonard Cohen’s.”

“Hallelujah” has become an unexpected staple in the live act of heavy metal band Alter Bridge, initially an offshoot of the mega-selling hard rock band Creed. (Coincidentally, on my way to meet up with Alter Bridge singer Myles Kennedy prior to a concert by his band, a cellist was playing “Hallelujah” in the Union Square subway station.)

In a downstairs lounge under the Best Buy Theater, in the heart of Times Square, Kennedy (who also sings in a band led by guitarist Slash, and filled in for Axl Rose when Guns N’ Roses were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2012) recalled the first time he heard Buckley’s recording of the song, saying, “It was one of those lifechanging moments. I was in my house in Spokane, Washington, I think it was January of ’95. I had just gotten the Grace record and sat down and was listening to it, and that song came on and I was completely dumbfounded. Then I got to see him perform it about five months later in Seattle.

“The thing about Jeff’s interpretation is that there’s a certain melancholy, a certain longing. What I got out of it was the idea of surrendering, just total surrender to this thing called love. The vibe I get in reading that lyric, or in singing it, is that it’s not necessarily perfect; it’s painful. But surrendering nonetheless. And it’s beautiful.”

Amanda Palmer, who has often performed “Hallelujah” live, takes a bit of a contrary view (as she does with most things); she said that she appreciates Buckley’s interpretation more than she loves it, and finds his reading more calculated than truly organic. “I think Jeff Buckley was brilliant, but his version of the song always struck me as too technical,” she said. “But I get totally why that version hooked people, because he also knows what you can’t do with that song, which is that you can’t get so overwrought that you lose the plot. You’ve got to deliver it just right, and he’s got this angelic, fantastic, otherworldly voice.

“I think the other important part of that song is you don’t fucking over-orchestrate it. You don’t put swelling strings and a symphony behind it. That song works best when it’s just stripped down.”

Jeff Buckley’s following may not have been as big as Columbia Records had hoped for, but it was certainly fervent. And as these listeners discovered Buckley, some of them were also being introduced to the older Canadian gentleman who had a songwriting credit on the album. While Buckley didn’t know Cohen’s work when he first started performing “Hallelujah,” by the time Grace was released, he had become a student of the man’s music.

“He developed a tremendous respect and reverence for all things Leonard,” said Steve Berkowitz. “Like Dylan, Led Zeppelin, Miles Davis, James Brown—they were all of the highest order to Jeff.” Buckley was photographed holding a banana in tribute to the cover of Cohen’s I’m Your Man, and in the booklet for the expanded reissue of Grace, there’s a shot of him holding a copy of the Various Positions LP.

“The reason I did ‘Hallelujah’ was because of the song, and not because of Leonard,” he told MTV’s 120 Minutes alternative video show. “But you can’t help but admire him.”

When Norah Jones first heard “Hallelujah,” she didn’t know that it was a cover. “Then I also realized Leonard Cohen wrote ‘Everybody Knows,’ which I knew from Concrete Blonde doing it on the Pump Up the Volume soundtrack,” she said. “I also used to listen to Nina Simone’s version of ‘Suzanne,’ so then I was like, ‘Who is this guy?’”

If Leonard Cohen was the author of “Hallelujah” and John Cale was its editor, Jeff Buckley was the song’s ultimate performer. A decade after its original recording, the song had found its defining voice, and the Grace recording would essentially become the version against which future versions would be measured.

To this new generation of cool kids, “Hallelujah” belonged to Jeff Buckley. Having honed his performance of the song in tiny Manhattan clubs, he was ready to take it out to the world with complete confidence. Often even a famous artist will offer deference or defensiveness when covering someone else’s composition, but not Jeff Buckley. (“Jeff was never intimidated by a song,” said Glen Hansard. “That’s kind of what made him great.”) He was delivering “Hallelujah” with an intensity that was almost mystic, and a very different manifestation of the ecstatic, “holy hallelujah” in Cohen’s original.

Just how much he had taken on a new and specific meaning for his “Hallelujah” was evident in the razor-edged, street-romantic way Buckley introduced the song onstage in Germany in 1995. “It’s not the bottle,” he said. “It’s not the pills. It’s not the face of strangers who will offer you their lines and hot needles. It’s not the time you were together in their place—so perfect, like a second home. And it’s not from the Bible. It’s not from angels. Not from preachers who are chaste and understanding of nothing that is human in this world. It’s for people who are lovers. It’s for people who have been lovers. You are at last somewhere. Until then it’s hallelujah.”

Excerpted from “The Holy or the Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley, and the Unlikely Ascent of ‘Hallelujah’” by Alan Light. Copyright C 2012 by Alan Light, published by Atria, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, December 2012. Reprinted with the permission of the Author, all rights reserved.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.