If there were an Ambassador of Country Music, Bob McDill would be your guy, and I would have Don Williams as his envoy. The two would travel the world, and I’d have them in Syria negotiating a treaty. McDill would tell the one about getting two Nashville singers to sing in unison–you know, you’d have to shoot one of them–and President Bashar Assad would laugh out loud. Don Williams would grin through his Cheshire cat-like whiskers, and tell a couple of stories about Texas. He would then offer the Syrians some of the barbecued brisket he had in his briefcase. No wonder he smelled like mesquite.

Videos by American Songwriter

Bashar would say, “Hmm. I see what you mean,” and and give McDill and Williams a high-five. Alabama would be there, and they’d play McDill’s “Song of the South.” And oh, this is the way I’d have it, dear reader: the two would come home to Nashville right after lunch on that same Saturday. Had you forgotten that treaties are always signed on Saturday? They’d fly back on a rented plane with the boys in the band, and they would be greeted by Emmylou Harris and Crystal Gale and thousands of civilians from all over the world.

“I thought that one would be a hit,” McDill would proclaim. The DJs and record producers are there too, and so they’d start apologizing. And then–and this is the way I’d have it–at 7 p.m. that night over the airwaves of WSM–the whole world would be listening to the Grand Ole Opry, and we would be at peace.

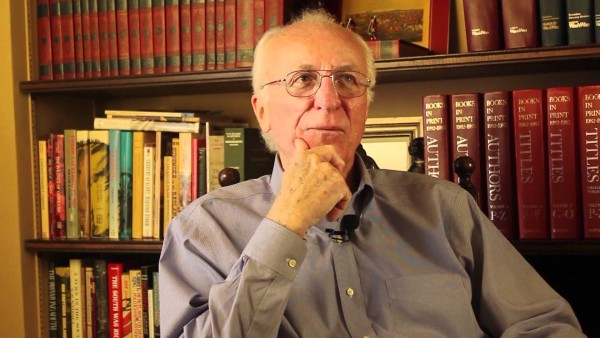

Nashville songwriting legend Bob McDill believes that music can change the world, even though it might just be one person at a time. “One thing all great songs have in common is that there is something there the listener can relate to,” said McDill. “Tracy Chapman’s ‘Fast Car’ is an example.” What McDill was referring to is that we are all faced with tough decisions–ones that will change us for the better if we make them, just as Chapman reminds us in her song:

You got a fast car

But is it fast enough so we can fly away?

We gotta make a decision

Leave tonight or live and die this way

For McDill, the decision to retire from songwriting in year 2000 was a tough one. He put up his guitar and pen for several reasons.

“There are some people who just don’t need to write anymore,” he said. “When you’re asked to write another up tempo song for whomever once again, it just gets stagnant. People just burn out. For me, I’m almost 70 years old, and I’ve got living to do.”

McDill has written scores of songs that are a significant part of country music history, and 31 of them became number one country hits. Plainly, there only a handful of songwriters who have achieved McDill’s level of success in Nashville. Born near Beaumont, Texas (that’s George Jones country by the way), McDill’s career as a professional songwriter began in 1967–he was 21–when Perry Como recorded “The Happy Man”. He had not yet moved to Nashville; he was living in Memphis at the time with Allen Reynolds. After college and a stint in the Navy, McDill moved to Memphis to write for black artists. However, both McDill and Reynolds decided to move to Music City in 1970.

“Everyone thought that Nashville was going to become a pop and rock-and-roll mecca for songwriters, but that didn’t happen,” said McDill. “It has now, but it took a long time.” Just imagine if everyone came to Nashville and discovered that the city did for them exactly what they intended. Would this not go against the whole point of trading off everything in pursuit of a career as a songwriter?

McDill’s first staff writing job was with Jack Music–the recently late great “Cowboy” Jack Clement’s publishing company. Staff songwriting jobs have always been important in Nashville because they provide a way for a songwriter to make a (barely) living wage while waiting, hoping, and praying for royalties. Back then, McDill made $25 a week, but Clement had also arranged for McDill a place to live, but things were very lean even after 1972 when Johnny Russell cut McDill’s first Nashville recording, “Catfish John”. The song was later covered by The Grateful Dead, and I can’t help but think that Jerry Garcia and Johnny Russell bare a striking resemblance to one another.

McDill’s draw eventually increased to $100 per week. The going rate now is around about $250 a week. That’s hard living, friends; yet, the songwriter will always survive. Thus, what can be said about the status quo for the Nashville songwriter is that is it isn’t a numbers game anymore; not insofar as how many songs a writer writes is concerned, but how long one can hold out and survive in different ways. And that, my friends, is because there are only a small percentage of staff writing jobs left in Nashville.

Some think that this accounts for the record enrollment into B.F.A. programs for songwriting in colleges like the one at Belmont University in Nashville. Instead of going to work, more people are going to college. There aren’t many jobs, and the economy is bad. As a result, people go back to school. In this case, so do the young songwriters.

“I don’t know a lot about what they do in these programs, but I’m on a scholarship committee at Belmont, so I think you can teach young people to make their songs better. I think you can teach craft,” he said. “But I don’t know about teaching creativity. I don’t know if that’s possible.”

McDill said that one of the things he tells young songwriters is that they need to do a lot of listening. McDill is, in Nashville fashion, a very deliberate writer. “You have to be there to write a song,” he said. Before McDill stopped writing, he would write everyday. He’d sit at 9 a.m. with a piece of paper at the piano or with the guitar, and begin. He wrote on average one song per week. As for the nuts and bolts of his writing process, the building of a song starts with a piece of a song. “It could be a lyric or a melody, or even a scene or story. It has to be something that draws the listener in,” said McDill.

When discussing the relationship between lyric and melody, McDill said, “For a song to be a great song, there has to be a wholeness there. But here in Nashville, we’re really big on lyrics.” McDill believes that Paul Simon is a great lyricist and songwriter because he is great at drawing the listener in, but also because he relates to them. Take the “Boy in the Bubble,” for example.

“The way those scenes go by is amazing. There’s so much in there that tells the story,” he said.

As for storytellers, one of McDill’s favorites is Robert Penn Warren. “Just the way he tells those stories. He’s so engaging. I don’t read his poetry though.”

In fact, McDill doesn’t read anybody’s poetry. He just doesn’t enjoy it. At the same time, he does think that songwriters have to draw from a poet’s tool bag.

“There are things like rhymes and alliteration, the poetic devices,” he said.

At the same time, to be sure, the writing of poetry occurs in the absence of melody. However, all great songs and all great literature have at least one thing in common, and according to McDill, “Whatever it is, it’s real. There’s something there that the listener can grab hold of.” Some of the time, it can be auto-biographical. Take, for example, “Gone Country,” McDill’s story about writing songs on music row.

If you’ve been in Nashville long enough, you will realize how important relating to what’s going on in the mind’s of people around you is the most important thing. This is what makes McDill and other great songwriters so special: there is a need to relate to others–a desire to communicate things that will enlighten the soul. The best songs can do this.

McDill told me that he was on an airplane the other day. He picked up the in-flight magazine, and opened it to see large photograph of Taylor Swift.

“This is so remarkable. Loretta Lynn appeared on The Tonight Show a couple of times, but imagine that. What if she was in a magazine like that? She did great out there, but she doesn’t cross boundaries like that.”

Isn’t it interesting that Loretta only flies if she absolutely has to?

McDill said that he was blessed to have worked with many interesting singers: Bobby Bare, Ann Murray, Don Williams, Allen Jackson, Doug Stone, Crystal Gale, etc. This list goes on.

“But I don’t listen to the radio anymore,” said McDill. “All those silly little phrases. I don’t get it,” he said. “Some of [the modern country music] lacks definition.”

If the state of country music is such that this newer brand of country does not yet know how to define itself, perhaps we should take some lessons from our Ambassador.

” ‘Good Ole Boys Like Me’ is the song that defined me,”said McDill. Here’s why:

I can still hear the soft Southern winds in the live oak trees,

And those Williams boys they still mean a lot to me;

Hank and Tennessee.

I guess we’re all gonna be what we’re gonna be,

So what do you do with good ole boys like me?

You put them in charge, Bob.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.