Videos by American Songwriter

How many times have you watched the opening scene from the classic TV western, “Gunsmoke”? Matt Dillon, Dodge City Marshall, stands in the street facing a gunslinger. The bad guy actually outdraws Dillon but fires and misses. Meanwhile Dillon shoots straight and true and the hapless gunfighter falls dead in the dust.

So what does all this have to do with songwriting? Well, you can be the fastest writer in town, but if you don’t take the time to give your song a direction, you might starve to death waiting for a cut.

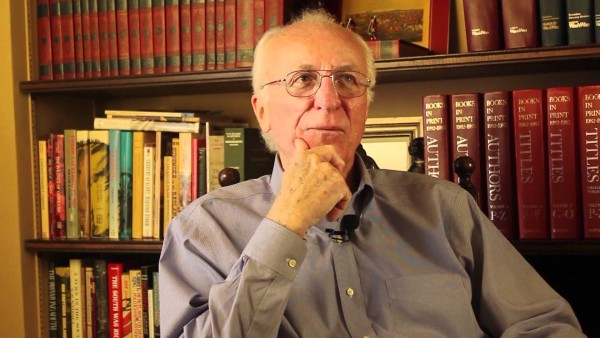

No one demonstrates the importance of direction in a song better than Bob McDill. He is songwriting’s counterpart to Matt Dillon. In a town of fast guns, McDill may well be the straightest shooter of all. He aims for the heart with his songs, and he rarely misses.

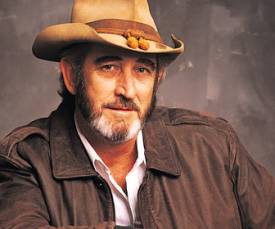

Since the early 1970’s, McDill has notched some 18 number one hits on the neck of his guitar, eight of them sung by Don Williams. Among McDill’s classics are such silver bullets as “Good Ole Boys Like Me,” “Amanda,” “Song Of The South,” “Everything That Glitters,” “Louisiana Saturday Night,” “Catfish John,” “Somebody’s Always Saying Goodbye” and “Baby’s Got Her Bluejeans On.”

But McDill is not only a straight shooter, he’s also a pretty fast hand himself. Since 1980 he’s had more than 70 songs he’s written or co-written recorded by various artists. His album cuts number in the hundreds.

His talents have earned him the respect of his peers and have made him one of the more celebrated songwriters in all forms of music. He’s been the Nashville Songwriters Association, International’s Songwriter of the Year twice (1976 and 1986). In addition, he’s been a finalist for that award four times, and in 1985 he was inducted into NSAI’s Hall of Fame. Four times his tunes have been finalists in the Country Music Association’s Song of the Year category.

McDill has had two Grammy nominations, 37 BMI awards and was that society’s Songwriter of the Year in 1985. Since signing with ASCAP two years ago, he has already received seven awards from that performance rights organization.

Born in Beaumont, Texas, McDill first arrived in Nashville in 1969, when he was signed as an exclusive songwriter by Cowboy Jack Clement. Among the other then unknown writers with Cowboy’s company were Dickey Lee, Wayland Holyfield, Jim Rushing, Allen Reynolds and Don Williams. These were the young turks of Music City and Clement, along with the late Bill Hall, were their musical gurus.

Ironically, McDill had moved to Nashville to write rock ‘n’ roll songs. He’d already had a few minor successes. While serving in the Navy he’d gotten two songs recorded – “Black Sheep” by Sam the Sham and “The Happy Man” by Perry Como.

But the predicted rock music bonanza never materialized in Nashville, so McDill eventually recorded his own album, Short Stories, on Clement’s JMI label. The LP contained “Catfish John” (co-written with Allen Reynolds) and “Come Early Morning,” both of which were subsequently recorded by Johnny Russell and Don Williams, respectively.

About his short-lived career as a recording artist, McDill notes “I didn’t want it that badly. Making records is fun but I didn’t want to be a star.”

What he wanted was to be a full-time professional songwriter. That he did want badly and he never backed down from the challenge.

“Sometimes I think if you want something bad enough, you don’t leave yourself any back doors,” he suggests. “All the guys who have something to fall back on, usually do.”

With nothing to fall back on, McDill left himself no choice but to push ahead. Like his songs, his own life had a direction. No doubt his tunes will be played, sung and enjoyed for years to come. And a few, like his “Good Ole Boys Like Me,” have such depth and richness that they must be considered art.

As McDill states in the following interview, he does not put much faith in predestination. And yet there is a line in “Good Ole Boys Like Me” which reads “I guess we’re all gonna be what we’re gonna be.” For Bob McDill, that’s being a songwriter.

A.S.: Is songwriting an art form?

McDill: I think songwriting can be art; most of it isn’t. I certainly know the difference when I hear one whether or not it’s commerciality or art. “Both Sides Now” is art; “At Seventeen” is art. Things that are more reflective or philosophical, or generally have a point of view.

A.S.: The definition is somewhat subjective though, isn’t it?

McDill: You can argue with people about what art is. Some people will tell you that any product of a creative thought is art. Well, I think that’s bull. If you do that, then a campaign for selling Bic Macs is art; that isn’t art. “Baby’s Got Her Bluejeans On” is not art. Whether or not it’s good art is subject to opinion, but at least it’s an attempt to say something.

A.S.: Is that a mistake young writers make – being too arty?

McDill: When I came to town everybody was too arty, too introspective. Songs were esoteric. That was usually the mistake young writers made. I think now the mistake young writers make is that things are too flippant, too puffy. There’s nothing of the writer in there. Young writers could probably benefit by putting a little of themselves in it and reaching for a line that’s a little more unique and more memorable.

A.S.: Is it easier for a young writer starting out today than it was when you began?

McDill: It’s not any easier to get good, which is the final question. Are you really good? It’s easier, I think, to have some success because of co-writing, and the fact that publishing companies are bigger and have more writers and everybody co-writes. It’s easier to be a part of a hit, but it’s not easier to get good. It’s no easier to be confronted with that empty page and be able to make something out of nothing.

A.S.: You’ve always had a reputation as a serious 9 to 5 writer. Is that still true?

McDill: I used to be a classic workaholic. Now it’s fashionable to be one and now that it is I can truthfully say I’m not one. The only reason I could take a vacation was so that I could rest my head long enough so that I could come back and get back to work. It wasn’t to enjoy myself. But you get to be about 40 and you think is this all I’m ever going to do, accumulate copyrights and money? There’s got to be more to life than this. So, a few years ago I started duck hinting again, and fishing and camping out. I also started collecting books and gardening. I’m trying to reflect and make life a little more fun before I look up one day and I’ve missed it all.

A.S.: Why do you try to keep regular writing hours?

McDill: I think the most important thing is to organize your time so that you put in a day. I’ve said this many times – you look at people who have long careers creatively, who didn’t burn out or go crazy or become alcoholics, and they all have one thing in common – they get up early every morning and do it and they quit at the same hour. They try all day and then the monkey’s off their backs; they’ve done the best they could that day.

A.S.: So there has got to be more than just inspiration?

McDill: If you write whenever inspiration hits you or you felt like writing, it’s insanity. That’s what happens to people – they come home at night and they haven’t done anything and they should have done something. They can’t sit down because they feel guilty. The thing to do is organize your time.

A.S.: What if you get inspired after hours, so to speak?

McDill: If you get an idea and you feel like playing with it, and you feel great about it, go do it. That part’s gravy; you don’t have to do it.

A.S.:Do you ever run into dead ends with song ideas?

McDill: All the time. I’ve got songs finished that I don’t think are ready, so I’m not going to put them down (demo them). I think it’s like bricklaying or anything else – practice. That’s another thing to be said for working every day – it keeps you sharp. If I take a couple weeks off I’m not as sharp as I was when I left. But you do get so you’re able to recognize a good idea and spend less time fooling around with a bad one.

A.S.: Do you do much rewriting?

McDill: More than most people, I guess. I hate to let them go if I know they’re just mediocre because you have to admit to yourself that you wasted all that time. It’s so competitive now that you really have to be good. If the songs aren’t good, you’re just playing games with yourself.

A.S.: What makes a song a hit?

McDill: I don’t know what it is. So much of it is luck and accident. I’m not one for predestination.

A.S.: Do you record full demos of your songs these days?

McDill: I’ve started making full demos. I think the town is changing and people want to hear a production along with the song. Country radio has opened up and they’ll play records that are more musical. If you put down something that musically is reasonably complex, you can’t tell the producer what you’ve got with a guitar/vocal demo. So you really hurt yourself; you’ve got to have a band. If I’d written “1982,” that doesn’t need a demo, but “She and I,” you have to demo that.

A.S.: What turned you on to writing country music, given that you came to Nashville to write rock ‘n’ roll songs?

McDill: When I heard George Jones sing “Good Year for the Roses,” I suddenly understood, hearing that song, what was going on. You’ve got to like it to write it, you know.

A.S.: Do you think you have an identifiable writing style?

McDill: I don’t know what my style is. You look at anybody who’s had a long run and they certainly have more than one trick.

A.S.: Your song “Amanda” is filled with ironies. Is that one of your tricks?

McDill: Anytime you can take a little couplet and make something happen aside from the overall song, then it’s really a strength. Sometimes you don’t have anything to say and you’re just reduced to alliteration or word plays. But every line ought to be interesting by itself – ideally. But you can’t always do that so you use any trick or method to keep it interesting.

A.S.: How did you come to write “Amanda”?

McDill: To be truthful, I was sort of inspired. I think I wrote it in about 30 minutes. It’s the last easy one I ever had.

A.S.: What approach do you take when you find an idea worth writing?

McDill: A lot of times I brainstorm everything that comes to mind. I’ll write down everything. When you’re flowing, get it all. A big mistake is to get a great idea and you feel yourself flow and you think you’ve got to get that first line. By the time you get that first line, all the rest of it is gone.

A.S.: It all boils down to love and hard work, doesn’t it?

McDill: James Dickey once said something like art doesn’t come out of a bunch of little old ladies patting you on the back at a tea or luncheon and bragging on your poem. It comes from the courage to face the awesome empty page. It does get grueling year after year by yourself with that empty page. But then, you can always go to lunch!

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.