“You could hear how these bands were influencing them,” says Byrne, who accompanied the band on a few short tours in the late ’80s. “But they really wanted to mix all those sounds with a base of traditional folk-country and distorted blues filtered through the British Invasion. It was really easy to see that if they somehow got out of the St. Louis area, people would get them. That’s why I was really evangelical about the band at the time.”

Videos by American Songwriter

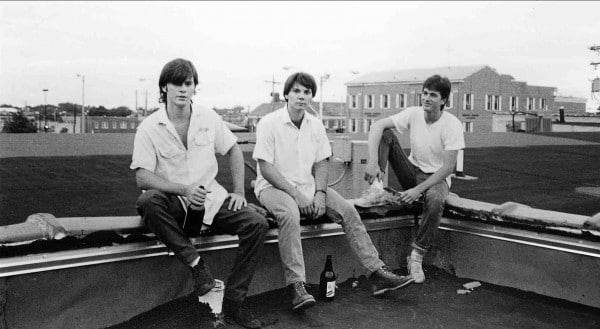

On Not Forever Just For Now, their self-released demo and unofficial debut, all of those influences gelled into a jangly sound full of shaggy melodies and cowlick guitars. Recorded with punk producer Matt Allison in nearby Champaign, Illinois, it includes early versions on a few of Uncle Tupelo’s well-known songs, such as “Whiskey Bottle” and “Screen Door.” Already Farrar wields both his guitar and his signature baritone with supreme confidence. Not Forever, Just For Now may have been rough around the edges, but it reveals a wildly ambitious band devising sophisticated arrangements, delivering an unpredictable power-trio attack, and penning songs that didn’t flinch to depict the bleak world around them.

* * * *

For the band’s first official album – which was released on Rockville Records, the label started by R.E.M. guitarist Peter Buck – Uncle Tupelo decamped to Boston in the dead of winter to work with Sean Slade and Paul Q. Kolderie (best known since then for helming albums by the Lemonheads, Morphine, and Radiohead). Rather than fine-tune the rough-and-tumble sound of Not Forever, Uncle Tupelo tightened everything up. No Depression turned out loud and jittery, full of sharply abrasive guitars, breakneck transitions, and pummeling rhythms. It’s simultaneously harsher and more refined than the demos, the sound of three musicians playing as one. “Jay’s voice was kind of like the bass cello in the orchestra,” says Heidorn. “When Jeff started writing and singing more, he was like the higher violins in the orchestra. I was right in the middle there, just soaking it all in.”

No Depression was, in other words, the work of a band with its sights set well beyond Belleville, and the world beyond the city limits was taking notice. Reviewing the album for the Austin American-Statesman in 1990, Peter Blackstock noted, “What seems to be their trademark technique – placing quick start-stop surges at unexpected intervals – adds a dynamic urgency to many of the songs. Guitarist Jay Farrar and bassist Jeff Tweedy have perfect voices for the type of music they play, balancing roughness with resonance in much the same way that their music combines melody with power.”

Even on the newly remastered edition of No Depression, the quietest song stands out as the loudest. A cover of the 1936 Carter Family tune, “No Depression” (also known as “No Depression In Heaven”) was more than 50 years old when Uncle Tupelo covered it, yet it sounded as topical during the first Bush Administration as it did during the Great Depression. It was not an obvious cover choice by a group of guys listening to Neil Young and Dinosaur Jr. “I first heard it on an old folk compilation that I dug out of my mom’s record collection,” says Farrar. “I think that version was by the New Lost City Ramblers. It just seemed like the sentiment of the song seemed to fit our surroundings.”

In direct contrast to the hydraulic guitars on the rest of the album, the “No Depression” track is entirely acoustic, with no drums, no bass: just a simple strum and Farrar and Tweedy’s cello/violins harmonies. “I’m going where there’s no depression,” they sing together, “to a better land that’s free from care. I’ll leave this world of toil and trouble. My home’s in Heaven, I’m goin’ there.”

For a band just starting out, however, death is neither a concern nor a consolation. St. Louis might just be far enough.

* * * *

In September 1995, Blackstock and fellow music critic Grant Alden mailed out the very first issue of No Depression, a magazine devoted to “alternative-country music (whatever that is).” By that point, Uncle Tupelo had already run its course after four albums and a famously acrimonious break-up. With Heidorn, Farrar had formed Son Volt and released an excellent debut, Trace. Tweedy had formed Wilco, whose ’95 debut, A.M., sounded lightweight and tentative. Alt-country had expanded from a trend into a movement, with Uncle Tupelo its patron saints.

The magazine originated, actually, in the summer of 1994 as an AOL discussion board. “Originally the board was just named ‘Uncle Tupelo,’ but the early regulars realized they were also talking a lot about bands such as the Jayhawks, Blue Mountain, and Jason & the Scorchers,” says Blackstock (who has returned to the Austin American-Statesman as a music writer). “They asked the AOL moderator to give it a broader name. The board’s regulars decided on ‘No Depression’ in part because they liked the reference to both Uncle Tupelo and to the original Carter Family song from the ’30s.” Blackstock was active on the board, and when he and Alden were discussing an alt-country magazine, “I told him I was pretty sure I knew what we should call it.”

By choosing No Depression as its name and by putting Son Volt on its inaugural issue, the magazine ensured that Uncle Tupelo and its debut would always be associated with alt-country, despite the band’s array of non-alt and non-country influences. The category is self-consciously limited, as the “whatever that is” on the masthead makes clear, but it also makes it difficult to gauge the album’s true legacy so many years later.

For one thing, No Depression is not generally considered Uncle Tupelo’s best album. Most fans rank any of their follow-ups much higher, and many still argue for Not Forever Just For Now as the highlight of their career. Nor is No Depression an especially influential album. Few alt-country bands mimicked its crunchy guitars or its quick staccato bursts of punk energy. Instead, their third album, March 16-20, 1992, exerts arguably the most lasting impact, influencing not only a raft of ’90s bands (such as Whiskeytown and My Morning Jacket) but also countless current string bands (including Old Crow Medicine Show and Trampled By Turtles).

Likewise, it’s misleading to call No Depression a first. Based on the new Legacy set, Not Forever Just For Now remains strong enough to count as a debut in its own right, not simply a blueprint for future triumphs. Furthermore, such a claim would ignore the contributions made by other bands in this genre: The Mekons, X, Jason & the Scorchers, and Rank & File, among others, spent the ’80s mixing punk and country. Alt-country mainstays The Jayhawks released their self-titled debut in 1986 – a full year before Uncle Tupelo lay down its first tracks. “It didn’t seem like we were doing anything extremely different from those bands,” Heidorn says. “I don’t see a legacy at all.”

And yet, No Depression survives. Perhaps its true legacy – what distinguishes it from subsequent Uncle Tupelo albums and what makes it sound so urgent and affecting still – is that it serves as a dispatch from “this world of toil and trouble” before Farrar, Heidorn, or Tweedy realized they could truly escape. For that reason it is their most rooted album, one defined not by fans’ expectations but by the musicians’ own dreams. “The most pervasive aspect of these songs,” says Farrar, “is the idea of moving on and seeing the rest of the world outside of Belleville.”

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.