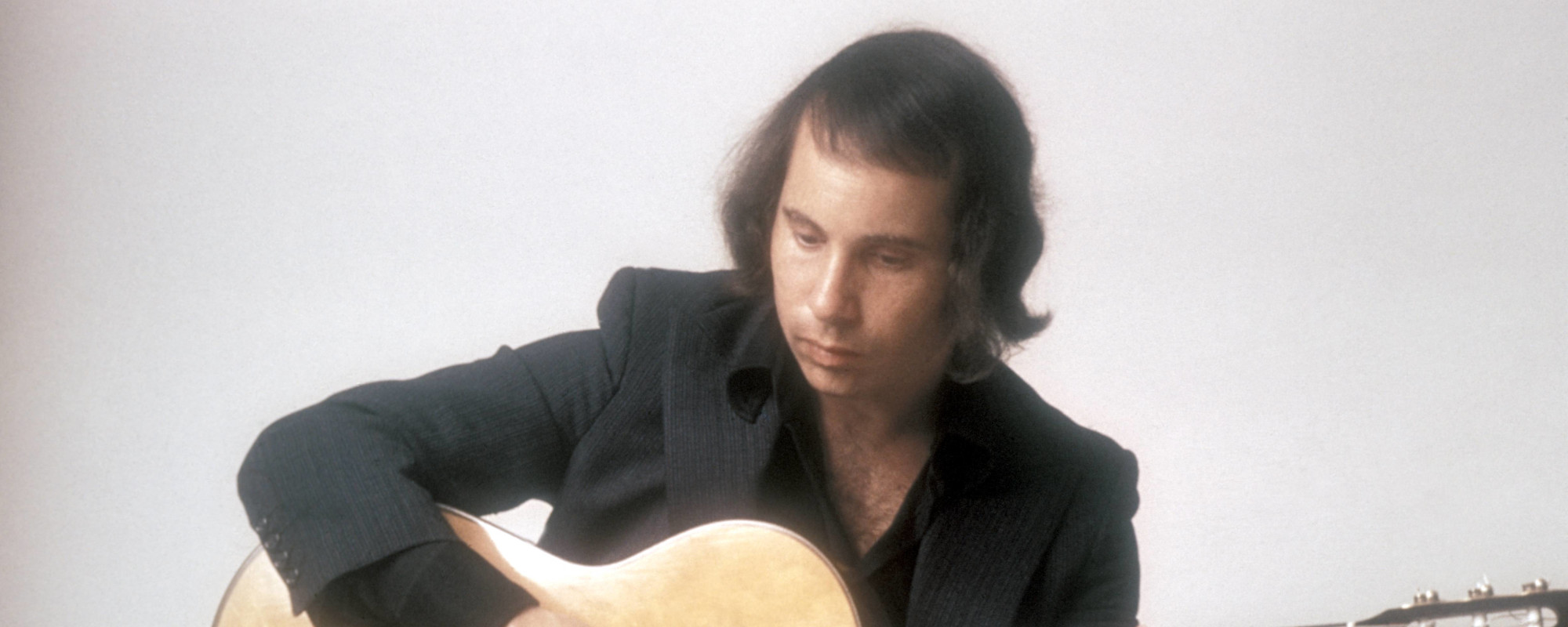

Ever since he made Graceland, released in 1986, Paul Simon has been writing songs almost exclusively by making a musical track first, and writing the song to that track. Prior to that, of course, he wrote songs on guitar. And given that the guitar method led to countless masterpieces of songwriting—from “The Sound of Silence” to “Bridge Over Troubled Water” to “Still Crazy After All These Years” and beyond—it seemed an unnecessary impediment to bring to a job that was already tough enough.

Videos by American Songwriter

When I interviewed him in 1991, he was working on the follow-up to Graceland, which became Rhythm of the Saints. We spoke about this method, which seemed like a really hard way to write songs.

“It is,” he agreed. “But there is no easy way.”

That is the essence of Simon. Since he was a kid with his eyes on the radio charts, dreaming of writing a hit, he accepted he could do things regular people don’t do. But he never thought it would be easy. “These are the days of miracle and wonder,” he declared with brave defiance. “And don’t cry, baby, don’t cry. “

And this change worked. Powerfully. Not only were Graceland and its follow-up Rhythm of the Saints two of the greatest-sounding albums ever, his method of writing songs to these exultant tracks succeeded in reinvigorating his artistic soul, greatly inspiring and empowering astounding songs, some of his strongest work ever. To these remarkable tracks of intoxicating rhythms, beautifully intricate electric guitar parts, stunningly fluid, soulful bass parts, spirited horn sections, rich vocal harmonies, accordion and more—he wrote many masterpieces of songwriting. Both whimsical and upbeat while deeply serious, both timely and timeless—such as “The Boy In The Bubble,” “You Can Call Me Al,” “The Cool, Cool River,” and more.

Subsequent albums took this track-first method to new places, such as the great acoustic-electronica Surprise, an album Simon produced with Brian Eno. Spring of 2011 brought So Beautiful or So What, in which he folded in found samples and loops, connecting past and present in powerful ways. In 2016, Stranger to Stranger poignantly added microtonal Harry Partch instruments to this mix, and percussion provided by flamenco dancers on hard floors.

Occasionally during this time, Simon returned to guitar-voice songwriting. Perhaps more than we know. But of the recorded songs, there are a few, and each is beautiful.

Of these, “Love and Hard Times” from So Beautiful or So What stands out as one of the greatest of Simon’s songs. Both musically and lyrically it is complex—a tour de force of melody discovered in his ingenious chord changes. Not to take anything away from the great songs written track-first, and the obviously great results, but few people can write songs like this one. My guess is that I am but one of his fans who wish he’d consider making a whole album of guitar-voice songs again—or at least more. What Simon can do with his voice, brilliance, and guitar is unlike that which anyone else does. It’s already ten years past the release of this song in 2011, and its charms seem only to have expanded.

We spoke about this one in some length back then. Here’s Simon in conversation about the story behind “Love and Hard Times.”

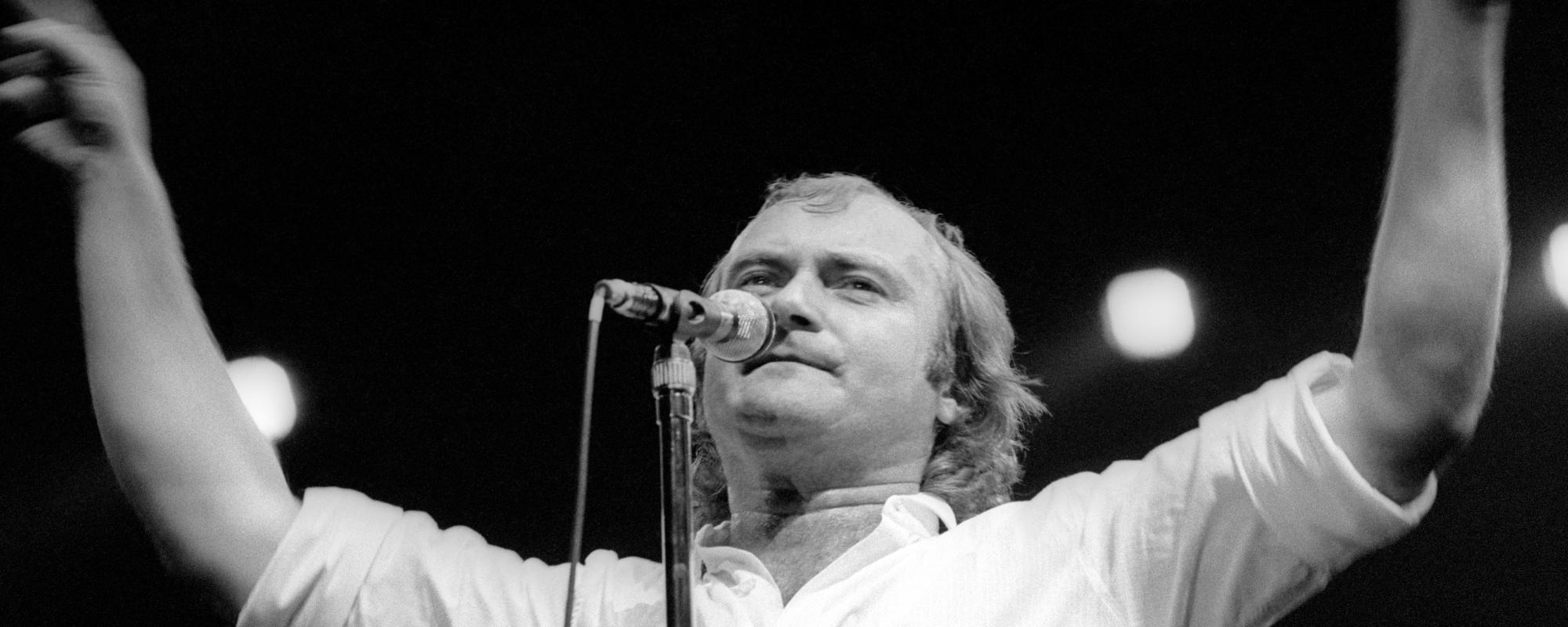

Photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe

PAUL SIMON: You know [“Love and Hard Times”] is more literary as an idea than I usually write. Meaning that it started as a theme, it wandered away from the theme, and then came back at the end to refer to the theme again, but from a different angle and in a different way, which made for a complete cycle lyrically—that was interesting.

Because it started with God and God leaving, and then it ended with “Thank God I found you.” That was really the pay-off to the whole thing. Because He left.

We generally think of songs as confessional or a story song. Yet this is both: it starts with the story of God and his son and then makes the transition to “I loved her the first time I saw her,” which is—

Edie [Brickell, his wife].

Yeah. We don’t get that in songs much. It’s like a cinematic shift from one scene to another.

Yeah, that’s right. You could say that. That it shifts. Because once the first two verses were over and I’d finished that part of the story, I realized that the rest of the song was going to be a straight-ahead love song. There was enough cynicism in the first two verses, and now I didn’t really need to go any further, and now the rest had to be pure love song.

So in a sense it is cinematic, in that it now changes to another story. As if you did a flash ahead in time or something. Or a flashback. But it’s two different places.

But the thing about it that’s interesting is that they do connect up. At the end. So that’s why I mean it’s more of a literary device than a song device.

In the past we’ve spoken about how you combine enriched, poetic language with colloquial language. In this song you do that both lyrically and musically; lines like “Well, we’d better get going” sound melodically conversational, whereas “there are galaxies yet to be born” seem poetic.

That’s right. And also it sort of changes key and shifts into a Jimmy Reed-shuffle for a couple of bars—when I sing “can’t describe it any other way,”— it slips into a blues, a shuffle. That’s one of the advantages of writing a song with no drums, just guitar. You can change on a dime.

That’s the only song on the album we heard prior to the album release, because you performed it at a bookstore in New York when you were writing it—a performance which is on YouTube.

Right. I started to do it live. After I finished it. To see what the reaction would be to it, and whether people would understand what I’m talking about.

It was amazing that on the album version you changed the melody and harmony at the end of one of the bridges from that live version. That melody and the changes are so complex, and yet you were still working on it. And your change was better.

Did I? I don’t know what that might have been—maybe the first quarter bridge where it went from a major chord with a 7th to a minor chord with a 7th. I changed that.

But yeah, as long as the process is going along, the opportunity for change is there. At a certain point, you close it down, and you’re finished. And you try to finish the record. Unless there’s something that’s really irritating about it. In which case I’ll go back.

When I originally recorded “Love & Hard Times” it was just with the guitar and the voice. And then I did the string session with Gil Goldstein. And when it was finished I said, “Gee, I had hoped this was going to be more.”

And that’s when I decided I was going to take Phillip Glass’s advice and put a piano on it. He also said it was a piano song.

And I said, “Oh, well, I just worked out this guitar part, and I hate to give it up.”

And he said, “Well, you can do both, you know. You can have both on it.” And that’s when Mick Rossi came in and did the overdub. That’s when we met, and now he’s in the band, which I’m thrilled about.

The song seems very much like a guitar-first song—

It is. It’s the second song I wrote for the album.

How did it feel to go back to that guitar-voice method?

A little bit awkward at first. And then, you know, I was a little bit apprehensive about whether I could do it. “Amulet,” which was my first attempt, was much too complicated. So I said, I’ll have to think more like a song. Not so much like whatever my fingers do. I have to try to put it into a structure that can be made into a song.

Although “Love and Hard Times” is a pretty complex structure for a song. It has different parts, and changes key several times. But nevertheless, it is a symmetrical structure. And then I realized, well, of course I can do this. And it’s just a question of patience.

You recorded it at your home studio in Connecticut, with Phil Ramone co-producing. In the past, you’ve recorded at studios like the Hit Factory in NYC. It was your first album recorded at home. How was that?

It’s very comfortable. Very comfortable. And Phil Ramone lives fifteen minutes away. So it’s easy for him too. We don’t have to drive into the city for an hour, and then park, and then at the end of the day be exhausted, and then drive back home on the Merritt Parkway when you’re tired. It’s very comfortable to not do that.

Also, I have so many choices of instruments there. I have all my guitars there. So if I decide that I want to choose a particular guitar that I wouldn’t normally carry to a studio with me, for example, if I say, “Oh, let’s try a Dobro on this sound, or let’s try a Requinto, or maybe I should try that Country Gentleman.” I have, whatever it is, twenty, thirty guitars that are there. So I have a pretty big palette to choose from in terms of guitar.

Also, I’ve started to collect a lot of percussion sounds. Especially bells. There are a lot of bells on this album. Overtones of bells used in different ways to create echo sounds.

That kind of thing, using bell overtones for echo, reflects the level of comfort you feel there—

Well, I am comfortable. With all this time available to me and no particular pressure—like I don’t have just two days in a studio or something—I have a lot more time for trial and error. Because a lot of things didn’t work, so they’re not in there. I’m playing different bell sounds or overdub sounds. Or, like the example before, of trying a Dobro.

You take it out and spend an hour figuring out the part and playing it, and then you say, “You know? It’s not that great, actually. So let’s go back to the Strat or something like that.”

There’s a lot of trial and error. And the trial-and-error aspects of this record were significant.

Given your full vision and love of recording, I wonder what Phil’s job is. Does he come up with ideas, or is he there to get your ideas down?

He does have some ideas, but he’s more a facilitator for what I want. And more than that, he’s somebody whose opinion I trust. So I don’t have to be an editor of my work constantly. I can throw out ideas, and if he says, “That one’s the best,” I don’t have to say, “Well, can you play them all back so I can check and listen?” Same with vocals. I do my vocal tracks. And I’ll do a lot of passes on a vocal.

“Love and Hard Times”

by Paul Simon

God and His only Son

Paid a courtesy call on Earth

One Sunday morning

Orange blossoms opened their fragrant lips

Songbirds sang from the tips of Cottonwoods

Old folks wept for His love in these hard times

“Well, we got to get going, ” said the restless Lord to the Son

There are galaxies yet to be born

Creation is never done

Anyway, these people are slobs here

If we stay it’s bound to be a mob scene

But, disappear, and it’s love and hard times

I loved her the first time I saw her

I know that’s an old songwriting cliche

Loved you the first time I saw you

Can’t describe it any other way

Any other way

The light of her beauty was warm as a summer day

Clouds of antelope rolled by

No hint of rain to come

In the prairie sky

It’s just love, love, love, love, love

When the rains came, the tears burned, windows rattled, locks turned

It’s easy to be generous when you’re on a roll

It’s hard to be grateful when you’re out of control

And love is gone

The light at the edge of the curtain

Is the quiet dawn

The bedroom breathes

In clicks and clacks

Uneasy heartbeat, can’t relax

But then your hand takes mine

Thank God, I found you in time

Thank God, I found you

Thank God, I found you

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.