Videos by American Songwriter

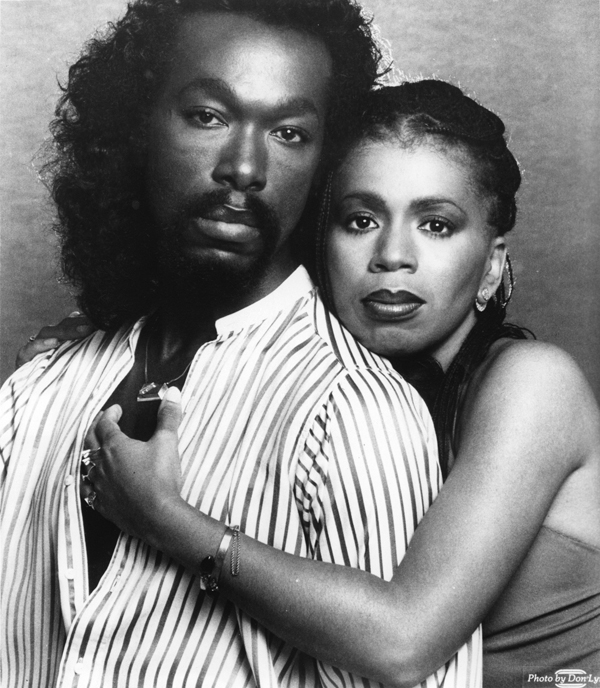

Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell sang, it has been remarked, like lovers, although they weren’t. Similarly, Nickolas Ashford and Valerie Simpson, the team behind one of Marvin and Tammi’s most enduring hits, “Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing,” wrote as if under the influence of amatory forces; even if, in the spring of 1968, when “Real Thing” emerged on Motown Records with the warmth of a sunflower, their relationship was still platonic (later, they married). The point of these reflections is that great songs, like all works of art, unify; they pull together what has otherwise been separate. Here, the sense of unity extends to every level of construction: not one element in “Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing” sounds discordant or out of place. In best Motown fashion, the song glides along like a precisely fashioned unit.

Ashford and Simpson have never earned much critical recognition, perhaps because their songs are so listenable, so smoothly tuneful, that the critic in us tends to withdraw from them. Songs this easy, it seems, couldn’t be great art—particularly when, as the story goes here, they are inspired by the slogan for a Coca-Cola commercial. But the simplicity of a song such as “Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing” is deceptive. A current of anxiety bubbles underneath the lyrics, which are tinged by the longing of two people who can’t be together as much as they would like: “I read your letters, when you’re not near/But they don’t move me, they don’t groove me like when I hear/your sweet voice whispering in my ear.” The writers have landed upon a concept—fear of separation—that informs a listener’s experience of their song, triggering specific memories. Those who have been pulled from loved ones, through unforeseen events or armed conflict (“Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing” was written during the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam war), can relate to the “picture hanging on the wall” that nonetheless “can’t see or come to me when I call your name.” Finally, at the song’s peak moment, with strings and voices swelling, Marvin and Tammi sing, “Let’s stay together,” as if in joyous determination to withstand the pressure of forces beyond their control.

Once the final chorus is changed to “so glad we got the real thing, baby,” it’s hard to imagine that doubt could ever have existed. Ashford and Simpson have surmounted the challenges they posed earlier, resolving all tension in the span of little more than two minutes. Still, the anxiety never fully dissolves: it is impossible to hear Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell perform without reflecting upon the tragedies (a brain tumor in her case, murder by a parent in his) that brought their careers to an early end. We can be thankful to Ashford and Simpson for providing both singers with an opportunity to sound, in spite of whatever else was going on in their lives, happy. Terrell’s delivery in particular is full of the wonderful asides and interpolations (“Talk to me”) that made her one of Motown’s most distinctive vocalists, while Gaye supports vocally with all the consideration he supposedly gave Terrell during her long illness. They weren’t to perform together much longer; on later hits (such as “What You Gave Me”), Simpson herself subbed for the ailing Terrell in the studio, in an unaccredited switch Motown would deny for years.

As brilliant as they were, Marvin and Tammi did not have the last word. One proof of a great song is its adaptability to new contexts and interpretations, and “Ain’t Nothing Like the Real Thing” has been revived successfully many times—most notably by Aretha Franklin, who gave it a luxuriantly romantic spin in 1973. Slowing the tempo, Franklin repeats “together” as a climactic shout, leading to a coda sparked by delicate interplay with a trio of ethereal-sounding backup vocalists. More jazzily introspective than that of Marvin and Tammi, no less powerful, Aretha’s version preserves the tightness of construction and flow that characterized the song from the beginning. Writing with one mind and heart, Ashford and Simpson ensured that the pieces of their marvelous composition would always fit together.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.