Videos by American Songwriter

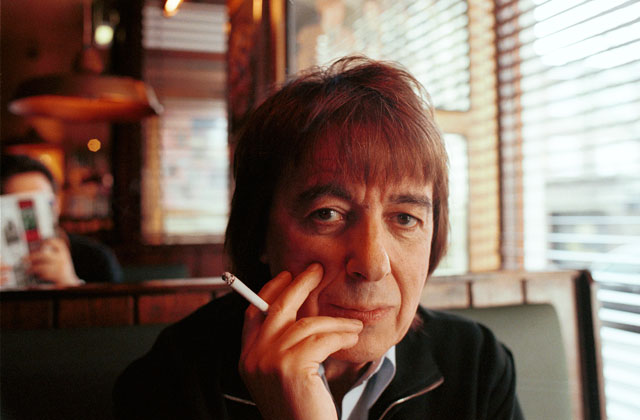

Bill Wyman left The Rolling Stones in 1992. He was one of the five founding members — along with Brian Jones, Keith Richards, Mick Jagger, and Ian Stewart. (Drummer Charlie Watts didn’t join until 1963.) In a recent interview with Rolling Stone magazine, Jagger said of the current incarnation of the Stones (which includes Ron Wood on guitar, Darryl Jones on bass, and sidemen like Chuck Leavell and Bobby Keys), “It’s a very different group than the one that played 50 years ago.”

In the intervening decades as a non-Stone, Wyman has busied himself with a series of projects, from recording and touring with his all-star group The Rhythm Kings, to writing books and managing his Sticky Fingers restaurant in London. As the Stones machine begins to crank up for a possible 2012 tour (it’s rumored he’ll rejoin the band for the proposed 50th anniversary concerts), Wyman talks about the difference between playing in the Stones and the Rhythm Kings, how he emulates the songwriting of the 1930s, and what he learned from some of the great bass players before him.

Did The Rhythm Kings grow out of your desire for a more eclectic repertoire?

It was in the very beginning. But it was also the same thing when I put a band together in ’85, for Ronnie Lane of The Faces, when he had MS and we did some charity shows with Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck, and we came to America and did ten shows. After that, I did an album, called Willie And The Poor Boys, and I called the band. Charlie Watts was on it with me, Ronnie Wood was on the video and Ringo. It was very successful, so that was pretty much a forerunner of the Rhythm Kings, because we did a mixture of roots music again.

It’s that whole mixture, and it’s lovely to do. There’s no pressure either. We’ve got no pressure to make hit records, or massive-selling albums, or record companies kicking us up the backside. We don’t have any of that so it’s just a pleasure to do it. You do it for the love.

The recent Rhythm Kings tour featured Mary Wilson from The Supremes as a vocalist. Do you remember the first time you met Mary?

Well, Mary, I knew her when we did the T.A.M.I. Show, November ’64 in California. We did the T.A.M.I. show and they were on it, The Supremes, as was many other people like Chuck Berry, James Brown, Marvin Gaye, Leslie Gore, and so and so on. We met her there and Diana [Ross], of course. They were the first ones who came over and talked to us, because we were pretty much not very well known at that time in America. It was nice to have somebody; the others didn’t take much notice of us, really. They came over and were really nice so we always thought nicely of them.

How did you come to collaborate with Madeleine Peyroux on “The Kind You Can’t Afford”?

I was in the south of France and I went to Nice Jazz Festival to see B.B. King, because I’ve known B.B. for years. So I want backstage and had a chat with B.B. And then I heard that Madeleine Peyroux was on the next [stage], we’d just missed her show actually. But I had her record so I went next door and had a chat with her and her band and we got on very well.

The following spring she got in touch with my office, because I gave her a card and said, “If you’re ever in England, just give us a bell, maybe we’ll go out and have a bite to eat and a drink and meet the family.” I sent her a song, so she rang up and said, “I want to know if I can come over and we can write some songs together.” So she came over to London and she stayed at a hotel and came over every afternoon for four or five days. We cut a bunch of ideas and demos. She chose the two songs that we did for her album, which turned out quite nice.

When I write for The Rhythm Kings I try to write in the style of the time. I don’t write what we do today. I’ve tried that before in solo recordings, it’s not quite where I’m comfortable at. I can get away with it sometimes if I do songs that are a bit tongue-in-cheek. I’ve had some success like that across the world, not so much in America, but pretty much everywhere else. So I decided to write songs that sounded like they’re from the ’30s or the ’50s, and it kind of works. I don’t know why, but it comes quite easily to me so I’ve written quite a lot of songs.

You’ve compared this type of songwriting with another of your interests, archeology.

You’re finding little treasures and bring them to life, exactly like you do with archeology. I find something from the 1920s, like Ethel Waters singing “My Handyman” or something like that, and I say to [Rhythm Kings vocalist] Beverley [Skeete], can you do this? And it comes out great.

What’s the difference between being on tour with the Stones and playing with The Rhythm Kings?

They’re very talented, my band. We’re on a 10-week tour. We had to learn seven new songs for Mary, and six new songs for the band. We always try to do new songs; every singer in the band has a new song. So it’s 13 new songs to learn, and then sharpen up on all the other stuff that we do, because we don’t play that regularly. We did it in three afternoons. We go over to the rehearsal rooms and we do that. We cut the tracks and make sure we’ve got them all right and then we go on the road. Which is a bit different than Stones. When I was in the Stones, we used to rehearse for a month, to learn songs we’d been playing for thirty years. It was quite bizarre. It always irritating to me how long it took to do things. But it worked for them, and it worked very successfully.

Obviously the Rhythm Kings are very versatile in all these kinds of styles. Why weren’t the Stones as versatile?

They are in a way, but they’re just lazy. [Laughs] Or they’re just casual about it. When I do rehearsals we say, “Alright, 12 o’clock ’til eight.” Everybody gets there at 12 o’clock and we all leave at eight. If you say that to the Stones — “Alright, rehearse tomorrow from 12 ’til eight” — me and Charlie will arrive at 12 o’clock. Mick will arrive at half past one. Woodie and Keith will arrive at four o’clock. That’s the way it always was. And if it’s an evening session, sometimes people won’t even arrive at the studio ’til 3:30 a.m., and then you’ll work ’til one o’clock the next afternoon. It’s bizarre, but that’s the way it worked. That’s the way Keith worked. It was very, very difficult for me — and Mick wasn’t very happy about it — because we’re more, sort of, organized with our lives. Keith just flies about, he’s a free bird. He doesn’t stick to times or anything. That’s the way he is so you have to live with it. Sometimes it can be very frustrating.

When did you first start writing songs for Rhythm Kings?

I had some ideas when we first went in the studio, and we cut like eight tracks in three days. We do every thing in three takes, maximum. If we don’t get it in three takes, we just dump it and move on to the next song, no matter what it is. A lot of them are take one, and quite a few are take two. So you don’t mess around. I was finding ideas and so was Terry Taylor, my co-writer. We’d do the music and I’d put the lyrics together and then we’d present it to the band and one of the band would [sing] it.

I just tried to capture the atmosphere of the time of what I was thinking that song suited, whether it was the late ’30s, or whether it was jump music, around the time of Fats Waller, trying to use the local slang, try to use the kind of melodies they would sing backing vocals to, and different kind of horn arrangements.

Jeff Beck said to me, “Where did you get ‘Motorvatin’ Mama’? Where’d that come from, who did that originally?” I said, “No, I wrote that.” He said, “Get out of it, that’s a ’30s song.” I said, “I wrote it, it just sounds like one because we made it sound like that and I’m using lyrics that are familiar to that time.” And then he said to me, “Who plays bass on it?” And I said, “I do.” And he said, “No you didn’t. That’s a double bass on there and you don’t play double bass. Your hands are too small.” That’s me playing bass but I’m trying to make it sound like a double bass, because that’s what was being used at the time.

Who were some of the bass players that influenced you?

Willie Dixon is the principal one. Most of the other [double bass players] in the ’30s, I don’t even know their names. We’re not aware of who they are. I always idolized Willie Dixon, particularly, because he was on with Chuck Berry and Little Walter, Howlin’ Wolf, and many others at Chess. I tried to play with the simplicity of Duck Dunn of Booker T.’s band. He’s a great mate of mine, and I idolized him before I even met him. He played with simplicity; he was there, he didn’t stick out. He didn’t get in the way of anybody. He just did the right things in the right spaces. His timing was perfect. That’s what I tried to do, right from the very beginning and it worked for me — that’s my style.

I’m not a busy bass player. I’m not a Stanley Clarke or anyone like that. To me, they should be playing guitar, not bass. And Ronnie Wood does that. When he played bass in the Stones sometimes, he used to say, “What do you think, Bill? Do you like me bass?” And I said, “Ron, it sounds like a solo guitar bit.” Doo-ding-ding, it’s all up there [meaning high notes on a bass guitar]. You need some balls in the bottom. I always kind of joked to him about it. You leave the space for other people, you don’t fill it in with the bass. Leave lots of room and let the track breathe from underneath. Piano can add to that, or whoever. Guitars, organ, horns. But don’t fill it up.

Proper Records has recently released a collector’s edition box set of all The Rhythm Kings recordings.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.