When Jamie Oldaker passed July 16, he was merely the latest of the surviving grandmasters of the “Tulsa groove” to succumb to time and death. Steve Ripley, who co-founded Tulsa’s double-platinum country-rock band the Tractors with Oldaker, died in 2019. Leon Russell, the genre’s best known artist, died in 2016. So did Steve Pryor, one of the genre’s many overlooked players. J. J. Cale, the genre’s most influential artist, died in 2013.

Videos by American Songwriter

Despite these losses, the infectious Tulsa groove is still thriving in the city itself, even if it has faded from the national consciousness. The evidence can be heard on two new albums. Twenty of the town’s younger musicians have combined forces to pay tribute to the city’s older musicians on the 17-song, single-disc album Back to Paradise: A Tulsa Tribute to Okie Music. At the same time, three older musicians—Casey Van Beek, Walt Richmond and Ron Getman, all co-founders of the Tractors—collaborated on Van Beek’s first solo album, Heaven Forever.

Both records showcase Tulsa’s signature sound: that relaxed, slithering rhythm that occupies the no man’s land between swing and straight time. It contains elements of Bob Wills’ Western swing, Merle Haggard’s honky-tonk, Albert Brumley’s gospel and Lowell Fulson’s blues. All these of these singer-songwriters had crucial ties to Oklahoma: Brumley and Fulson were born there; Wills spent his greatest years leading the house band at Cain’s Ballroom in Tulsa. And Haggard’s “Okie from Muskogee” is a winking nod to his Oklahoma-born parents.

The Tulsa groove was created by young white rock’n’rollers learning from older blues musicians on Tulsa’s northside, the remnants of the neighborhood destroyed by the 1921 massacre so chillingly depicted in HBO’s Watchmen. Perhaps Cale said it best when he declared, “We were just trying to play the blues and didn’t know how, so that’s what we came up with.”

“Tulsa is such a crossroads between east and west,” says Paul Benjaman, who sings lead for five songs on Back to Paradise. “The accents here go from the deep South to the Midwest. All the white guys were learning the blues from the race records on the radio and from black musicians like Flash Terry on the north side of town. All these very economical players were mixing swing with a straight beat, and that tension was very interesting.”

“Bob Wills swung not because the drummer was doing some fancy swing thing,” Ripley told me in 1998, “but because the drummer was very steady and everyone else was playing against that beat. That shuffle against straight time is the Oklahoma thing; that tension between the steady pulse and everyone else playing against the beat is what makes it exciting. When Jamie plays drums for us, he’s rock-solid and the rest of us are all over the place.”

“It’s just an attitude, a feel,” adds Van Beek. “It’s not that in-your-face, nervous stuff that some people play. In Tulsa, we don’t do anything else; that sound is what we do. There’s a bunch of young guys doing it too. I like Paul, Jesse Aycock, John Fullbright, all those guys. They call themselves the New Tulsa Sound. We’re passing the torch, and they’re carrying on the tradition.”

“When J.J., Leon and those guys kick into gear,” Fullbright concludes, “they never stray from it; it’s like a perfectly tuned German watch. You listen to that and say, ‘This is a force.’ They took gears from the blues, from rock’n’roll, from country, and wound it into this tight coil. J.J. would sit on stage, intro the song, let the band start to play, and wait three or four minutes before he started to sing, until he was sure the band was locked in tight.”

After leaving his hometown of Tulsa at age 17 in 1959 to work with Jerry Lee Lewis, Phil Spector, the Beach Boys, the Flying Burrito Brothers, the Rolling Stones, Joe Cocker and George Harrison, Russell invited many of his fellow Okie musicians to join him in L.A.: Cale, Oldaker, Jim Keltner, Carl Radle, Dick Sims, David Teegarden, Jesse Ed Davis, Roger Tillison and the future leader of Bread, David Gates. A bunch of them wound up playing for Eric Clapton and/or Bob Seger.

Russell launched Shelter Records with Cocker’s producer Denny Cordell in 1969, enjoyed some early success and then shifted his center of operations back to Tulsa in 1972. Most of his Okie pals also made the return trip as did a few California friends such as Van Beek and Don Preston. Russell opened the “Church Studio” in Tulsa and the “Lake Studio” out in rural Oklahoma on the Grand Lake of the Cherokees. It was at the latter location that filmmaker Les Blank shot the bacchanalian documentary, A Poem Is a Naked Person.

After a few years, Russell had moved on again, and the two studios eventually fell into disrepair. But it’s a sign of Tulsa’s current revival that both studios are being renovated. Brian Horton, the owner of the city’s Horton Records, and local guitarist Jesse Aycock, co-founder with Todd Snider and Dave Schools of the Hard Working Americans, had the idea of recording Return to Paradise at the “Lake Studio.” It was the first album tracked there since 1978.

“You could still see how it was when Leon Russell was there,” says Benjaman, J.J. Cale’s most persuasive disciple. “The control room and the large room were the same; you could fit 20 people in there. Most of the things were recorded live. We did it in four days with a house band, though we switched out some members for certain songs. Jesse and I were on all the tracks; the rhythm section was Paddy Ryan on drums and Aaron Boehler on bass. The concept was to take a bunch of old tunes by Tulsa musicians done by what’s going on around here now—connecting the past to the present.”

Meanwhile, Van Beek and Richmond from the Tractors had been recording demos at Richmond’s home studio in Tulsa with help from Jimmy Byfield, another under-the-radar local musician, though his song “Little Rachel” was recorded by Eric Clapton. The connection was Richmond, who played keys on seven different Clapton albums plus projects by Cale, Seger and Bonnie Raitt.

When Mike Kappus, Cale’s longtime manager, heard the recordings, he was so excited he convinced the Little Village Foundation to release them as an album. In addition to a handful of unreleased originals in the Tulsa style, the record includes Cale’s “Since You Said Goodbye,” Peppermint Harris’s “I Got Loaded” and Huey “Piano” Smith’s “Roberta.” It sounds like a long-lost Tractors album.

The Tractors were the brainchild of Ripley, who had been running Russell’s old “Church” studio and knew all the musicians in town. He thought that if he tilted the Tulsa groove a bit in the hillbilly direction it could go over on country radio. He recruited Van Beek, Richmond, Getman and Oldaker to record an album on his own dime. He brought the tapes to Nashville Arista, who put it out as The Tractors. The result was a #2 country, #19 pop, double-platinum album.

“I loved that combination of rock and country,” Van Beek recalls, “even if it was marketed under the country umbrella. But it wasn’t the regular fare; we had horns, a rock thing and that Tulsa rhythm, the complete opposite of what Nashville was doing at the time. And it worked.”

On Back to Paradise, Ripley’s “Crossing Over,” a song from the 2002 solo album <I>Ripley,</i> is sung by Fullbright, who moved to Tulsa four years ago. He also sings Leon Russell’s “If the Shoe Fits” and Hoyt Axton’s “Jealous Man” and plays funky piano on 14 of the 17 tracks. These performances reveal another side of Fullbright, who is better known as one of the most gifted singer-songwriters of his generation. As such, he serves as a bridge to another crucial part of the Oklahoma music community: the folkie troubadour scene that includes Samantha Crain (see here), John Moreland (see here), Parker Millsap, John Calvin Abney and more.

You might think that these literary lyricists and acoustic-guitar strummers were inspired growing up in Oklahoma by the state’s most famous songwriting son, Woody Guthrie. But Fullbright, who actually grew up in Guthrie’s childhood hometown of Okemah, says that isn’t so.

“Growing up, I didn’t know about Woody Guthrie, J.J. Cale and Leon,” Fullbright confesses. “The only Oklahoma singers I knew about were Reba and Garth Brooks. I knew Woody wrote ‘This Land Is Your Land,’ but it wasn’t until I got into Bob Dylan and learned he was a fan, that I paid attention. I thought it was cool that Dylan liked someone from Oklahoma. I was floored; it was like Bob Dylan was a friend of my cousin. We didn’t sing ‘This Land Is Your Land’ in school, because if you talk about Woody, you have to talk about unions, about oppression. Woody is such a political character, it’s hard to separate the music from the politics.”

Fullbright was in middle school in the early ‘90s when he discovered his mom’s copy of Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits. He was so entranced by the combination of words and music that he started seeking out all of Dylan’s albums and then all the albums that were either influencers or influencees of Dylan. That led the Okemah youngster not only to Guthrie but also to Steve Earle, Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt—three Texans who put a Southwestern spin on Dylan’s innovations.

“I’ve always played music in some way,” Fullbright points out. “I started classical piano before I was 10. I took lessons all through high school and did recitals three times a year. I was always writing moody poetry in high school, then I started mixing those worlds together the first year of college. I got heavy into Townes and writing songs that were as much prose as catchy songs. That’s when I started taking it all seriously, maybe too seriously. Anytime you catch yourself writing ‘betwixt’ instead of ‘between,’ you need to back off.”

The piano proved an important tool. Even before he got into Guthrie, he got into Bob Wills. Fullbright could play those Texas swing numbers on the keyboard and could imagine himself leading a big swing band at Cain’s himself. That never happened, but it did allow him to play with more expertise, more rhythm and more melody than most of his singer-songwriter colleagues. And when he discovered the California piano men Randy Newman and Tom Waits, he found his greatest role models.

“If I listen to Waits and Newman too much,” Fullbright says, “I just get disappointed in myself. They’re too good. But I try to listen to pop music and country music every day. I don’t listen to it for the recording; I listen for the melody and the feel of it, the structure of it. I like to analyze it like a painting. When I went for a walk today, with my earbuds in, I listened to a Ray Stevens song, then the new Eminem album, then my Margaret Atwood book. I thought, ‘That’s quite trio: a racist, a rapper and a feminist all in a quarter mile.’”

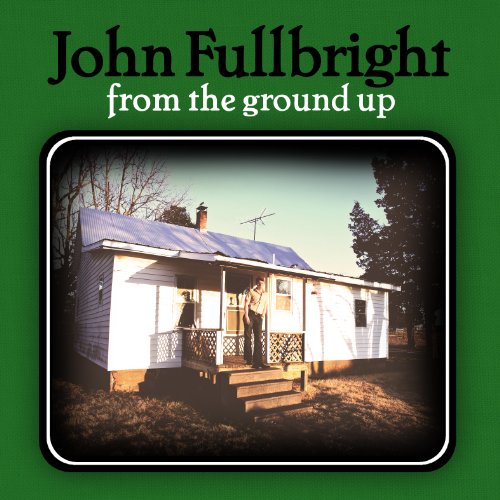

This unlikely mix of influences has resulted in some stunning songs. Live at the Blue Door, recorded at Oklahoma City’s showcase club in 2009, showed Fullbright’s early promise. His first studio album, 2012’s From the Ground Up, deserved its Grammy nomination for Best Americana Album. His second studio album, Songs, was even better. And we’re still waiting for the fourth album.

“My next record’s coming together,” Fullbright reveals. “I’ve recorded aspects of it, a lot of songs, but whether it’s coherent and cohesive is another question. It’s a matter of time and money, but it’s also a matter of getting healthier mentally and physically. This time in Tulsa has actually been a really good break, a way to hit reset. One of the revelations of doing all these sessions with other people here is getting to know all these great studios and players. Musically Tulsa is one of the more inclusive places I’ve been. If you go out to see a band, chances of you ending up on stage are very high.”

“John found a circle of musicians here that he felt comfortable sitting in with,” confirms Benjaman. “He may show up at a gig and just start playing keyboard. I’ll look around on stage, and there he is. He’s given us some great touring opportunities. I got to do the Cayamo Cruise as part of his band. His songwriting raises the bar for everyone else in town. I’m always bumping ideas off of him. I’ll have a new record wrapped up by the end of this year, and I’ll release it in the spring.”

Outside of the two big cities (Tulsa and Oklahoma City) and the two college towns (Norman and Stillwater), Oklahoma has a lot of open space and not that many people. It’s ranked 19th out of 50 states in size but only 35th in population density. But that isolation has insulated the local songwriters and players from outside influences and allowed them to come up with something original. And it has encouraged them to bond with one another.

“Like any music scene,” says Crain, “this one comes from a few key spots where people congregate for playing live music: the Colony and Mercury Lounge in Tulsa, the Conservatory in Oklahoma City, the Deli and the Opolis in Norman. People played the same places and got to know each other and played on each other’s records. It comes from proximity and a scarcity of places to be. I have definitely had deep conversations with John Calvin Abney and John Fullbright about songwriting. What you have here in Oklahoma are these singular voices, whereas in most music scenes, people tend to blend together and sound the same.

“What makes the Tulsa sound work,” Benjaman continues, “is having rhythm sections and soloists that we share in the studio and on gigs. That kind of communal way of making music and hanging out was true back in the day and it’s true now. David Teegarden is still around running a studio, and he tells us stories. Jamie Oldaker once described the Tulsa groove to me as trying to play Jimmy Reed tunes, only to have some of them playing straight and some of them swinging. It ended up not sounding like Jimmy Reed but not sounding like anything else either.”

You can get the album on BandCamp, by clicking here.

Twenty Tulsa musicians will play the album-release party for Back to Paradise at the historic Cain’s Ballroom in Tulsa on Saturday, August 29.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.