Videos by American Songwriter

I think what a lot of people don’t understand about songwriters is that to do what we do – write songs we want the entire world to hear – it takes a true measure of courage. You’re in the business of putting your heart and soul out there in the world, where any number of people feel free to criticize and tear down what you’ve done. And it hurts. Songwriters, except if they’re genuine hacks, feel things very deeply. And when somebody tears into one of your songs, it’s like an arrow straight to the heart. Because, as Randy Newman told me, songwriting is “life and death.” It’s everything. Nothing means more. Few things achieve the kind of bliss a songwriter experiences after completing a great one. And few things hurt more than unwarranted criticism. Sure, constructive criticism is good and even necessary. But destructive criticism, well, that is quite a different matter.

The good news is that you’re not alone. All the great songwriters of this planet, with very few exceptions, take criticism much deeper than they do praise. James Taylor told me that after Rolling Stone dubbed him the worst of all the “confessional songwriters,” it paralyzed him for years. But it makes sense: Anyone who could write something as poignant as “Fire and Rain” is obviously a man who feels things very deeply.

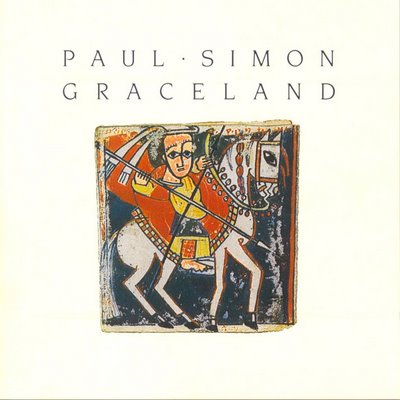

And all the songwriters I interviewed for my book Songwriters On Songwriting, and those who will be in the next volume – testified to some level of critical damage. Paul Simon said he was so downhearted by the poor reception of his album Hearts And Bones (which contains some of the most beautiful songs of his career) that he felt nobody cared anymore, “nobody was listening.” But rather than indulge in self-pity, he follo wed his muse to South Africa and recorded the beds of music that became Graceland.

Figuring he’d lost his audience, he drowned his sorrow in his craft, and created a landmark in popular music. “I don’t think it’s a good idea for a serious songwriter to pay attention to what [critics] say,” he said. “It’s just too hard. And it’s not informative. They don’t know what they’re talking about. Unless you write songs and make records, you just can’t know what it’s about.”

Often music execs can be as brutal as critics, if not more so. Dave Brubeck told me that when he brought “Take Five,” which Paul Desmond composed on his suggestion to their drummer Joe Morello’s 5/4 groove, to Columbia Records, they didn’t want to release it: “You don’t know the fights we had. It wasn’t in 4/4 time. The sales people said it could never work. Well, they were wrong. It worked.” To put it lightly. “Take Five” became the single most-played jazz record of all time.

Record companies being wrong is nothing new, of course. Capitol Records was among the many labels in the US that famously rejected The Beatles not once, but several times. The prevailing wisdom at the time was that only singers can have hits in America – think Sinatra, Elvis, Chuck Berry, Little Richard, etc. – but groups don’t. And per usual, that prevailing wisdom was entirely wrong, based only on the past with no vision of the future (the British invasion, which changed music forever and brought Capitol and others American labels enormous success.)

Tom Petty told me when he brought in Full Moon Fever, he was told his label wouldn’t release it. The reason? They didn’t “hear a hit.” He waited six months, by which time many of those executives who didn’t like it had been replaced. He brought in the same record, and they loved it. It became one of the hallmarks of an extremely successful career, garnering not one but four hit singles: “Free Fallin’,” “Running Down A Dream,” “I Won’t Back Down,” and “A Face In The Crowd.”

What is the moral? As the late great Ray Evans told me, “Never give up. Nobody knows.” Ray, along with his partner Jay Livingston, created songs so famous they seem to have existed forever, such as “Silver Bells,” “Que Sera Sera,” “Mona Lisa,” “Buttons and Bows,” and “To Each His Own.” Livingston & Evans, who were both in their 80s when I interviewed them in 1987, were one of my first-ever interviews, and one of the first times I had met songwriters of their stature. It amazed me then, as it still does today, to sit with a person who has written standards and realize they are finitely human, while their songs are timeless, and everywhere at once. They quickly set me straight about the music business.

“Every hit we had was turned down all over the place,” Ray said. “’Mona Lisa’ was not even going to be released. Nat King Cole said, ‘Who wants this? Nobody will buy this.’ … ‘To Each His Own’ was laughed at. They said, ‘Who wants a song with that title?’ … We played ‘Buttons and Bows’ for the head of Famous Music, and he said, ‘We might be able to get a hillbilly record out of it. That’s the best we can do.’” Even artists themselves often fail to grasp the greatness of their material, none more famously than Doris Day, who would only do one take of “Que Sera” because she so hated it that she didn’t want to sing it twice. It became the greatest hit of her career, and her theme song. “That’s nothing against her,” Jay said, “It’s just that nobody knows.”

Well, there is somebody that knows. That’s you. The songwriter. You know better than anyone – be it a critic, an executive, a singer, or even a spouse. You know what you’ve got. So trust your heart, and trust you’re song. And know you’re not alone.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.