Videos by American Songwriter

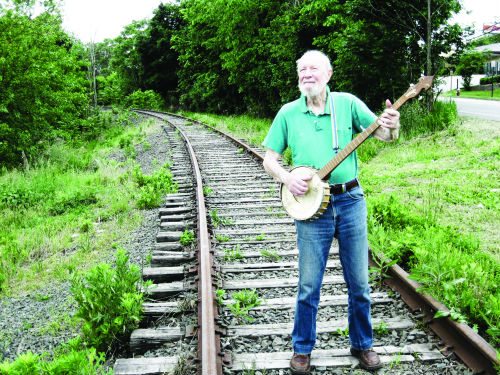

Pete Seeger died Monday night after being hospitalized in New York for six days. He was 94. This article originally appeared in our January/February 2013 issue.

Few are more iconic and deserving of inclusion in this column than Pete Seeger. At 93, this man long known as “America’s tuning fork” seems more visible than ever, the object of veneration around the globe, and is featured on a bevy of new CDs and DVDs. Like the just released album A More Perfect Union, which features 14 co-written new songs and guest vocalists Bruce Springsteen, Steve Earle, Tom Morello, Emmylou Harris, and Dar Williams.

Given that this American hero was actively blacklisted for years, kept off of TV and radio, his albums sometimes never even shipped out of the factories to stores, it’s a profound and welcome shift for our culture. Because Pete Seeger, besides being a songwriter of several classic American songs, such as “If I Had A Hammer,” “Where Have All The Flowers Gone?” and “Turn, Turn, Turn” is also an authentic historic link to the tradition of American popular music of the 20th century as created and developed with cohorts Woody Guthrie, Leadbelly, Cisco Houston, Malvina Reynolds, Lee Hays and the rest.

“All songwriters are links in a chain,” Pete said the first time I interviewed him back in 1988. It’s a foundational quote I’ve used a multitude of times since, and is the core to my book Songwriters On Songwriting: that despite genre, generation, style or format, and despite the music industry’s need to segregate songwriters and musicians into separate bins for maximum marketing potential, all songwriters are connected. And all songwriters build on that which came before, so that Woody’s stream of brilliance triggered Pete’s tuneful poetry, which in turn greatly influenced Bob Dylan, whose work impacted Lennon and the Beatles, and so on. It is all connected, and it’s a connection that continues forever, and remarkably not without the presence of Pete Seeger still living in our world.

The man never sold out. It’s true that he still lives in a handmade house in upstate Beacon, New York, with his wife of many decades, Toshi, where he still chops wood throughout the winter to warm his home. Last time I saw him – he was 90 – he carried both his banjo and his 12-string on his back and strode tall and long as Lincoln through bustling, brisk Manhattan. Although he hero-ized his old pal Woody Guthrie for years in his books and columns he’s written, Pete’s lived the more saintly life by far. While Woody walked out on more than one family more than once, Pete never abandoned his wife or kids, even when the blacklist made it hard to get good work. “I always made a living,” he said, but his sorrow at being so castigated seems never far, considering his magnitude of love for America and his traditions. He’s always been more than a popular entertainer. Like his dad, Charles Seeger, he’s a musicologist, in love with the music and traditions of this and all countries, and quite adept at expounding in great depth about the specificities of indigenous music throughout the globe, and the folk-process that allowed it to brew and expand here and abroad.

He’s also a man of some myth, still infamously blamed for threatening to axe Bob Dylan’s electric cords at Newport to keep the folk legend from “going electric.” It’s wildly untrue: Pete was simply disturbed that the mix – which was awful – made it so nobody could hear the brilliance of Dylan’s words. Pete was a champion of Bob’s songwriting from the start, elevating him to legendary status by performing and recording countless Dylan classics like “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” When I interviewed Bob, as soon as I breathed Pete’s name, Dylan said, “He’s a great man, Pete Seeger,” and has referred to him as a “living saint.” It stems from Dylan’s recognition that to Pete – as it was to Woody – these songs mean a whole lot more than a way to make a buck. They were truly folk songs – songs of the people – songs of hope and compassion, songs of trials, tribulations but also triumphs. Songs of the unions, of the working men. Songs of change. Bob, like Pete and Woody, recognized a solemn obligation to the world as a songwriter that was about the truth more than it was about popular entertainment. “See, to Pete and Woody,” Dylan said, “the airwaves were sacred. And if they’d hear something false, it was on the airwaves that were sacred. Their songs weren’t false.”

Pete’s never lived a false moment, even when the world tried to sway him. When his group The Weavers had pop success with chart-topping versions of Pete and Leadbelly’s “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine,” for example, he’d refuse to stay at the fancy hotels with his bandmates, preferring to sleep on a friend’s couch. Even now into his 10th decade, he still protests the wars and other evils in the winter winds on New York thoroughfares.

So this new era of people like Bruce Springsteen celebrating both the reality and the legend that is Pete Seeger is a beautiful if unexpected development in American culture. But it all makes sense. He’s the guy who did, after all, adapt the verses from Ecclesiastes (in his song “Turn,Turn, Turn”) that instructs with timeless wisdom, “To everything there is a purpose, and a time, under heaven.”

Paul Zollo’s interview with Pete Seeger is the very first chapter of his book Songwriters On Songwriting,” which features 62 interviews with legendary songwriters.

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.