Lou Reed told me he didn’t know how to write songs. “I do know how not to write songs,” he explained. “I know how to screw it up. So I spend my time removing the things that get in the way of it, the impediments that block it, the negative, attitudinal things. And by not doing those things, then I can start.”

Videos by American Songwriter

And when he did start, he explained, he didn’t start writing, he started listening. To the “permanent radio” in his head, the same one he’s been tuning into since the Sixties when he was writing miracle songs for the Velvet Underground; it’s a non-stop broadcast of verbiage both serious and hilarious, full of love and hate and magic and realism and much more. His job, he explained, was to write it all down. His main challenge, he said, was not how to write songs, but what to do with all the ones he received. “Writing an album for me is nothing,” he said.

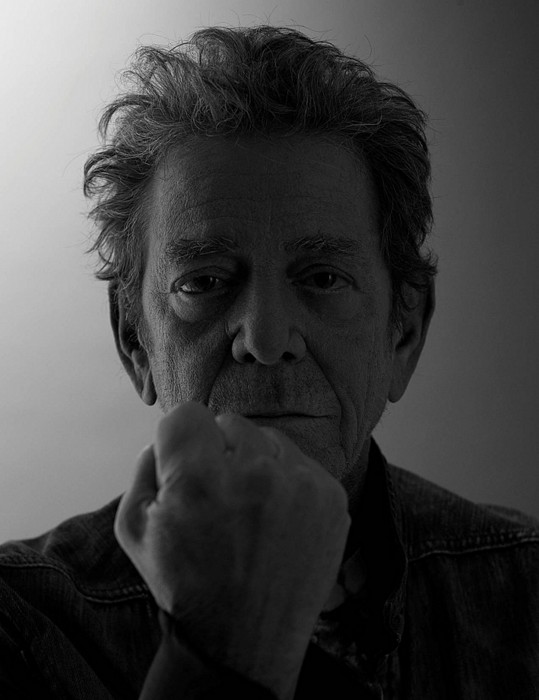

In 2000, we met up in Denver. He was 58, an age at which many of his peers were struggling to summon enough energy to do an oldies tour, and here he was onstage at the old Paramount Theater, spitting out astounding words to songs both new and old. The man was on fire.

I’ll admit that when I went to interview him, I was nervous, knowing of his famous hatred for journalists. My anxiety wasn’t eased when his tour manager told me, moments before the interview, that Lou had walked out on both of his previous interviews. “Don’t ask him about any of the old songs,” I was told. What? How could I talk to Lou and never mention “Sweet Jane” or “Walk On The Wild Side?”

But my fears were unfounded. As soon as I established my knowledge of his precise merger of poetry and rock and roll, we hit it off. I knew well his early hunger to merge the linguistic vigor of his teacher and mentor, the poet Delmore Schwartz, with the pure, fundamental force of electric rock and roll, and as soon as he knew I was in the know, we were off and running. And it was a heady, electric connection, and like his work, funny and serious simultaneously. We laughed a lot. I’ll never forget it. More than anything, I was impressed by his energy. Not only was he wiry and in impeccable shape (due to his daily regimen of martial arts, which was off the record, he said, as if it was a bad habit), he seemed to have limitless creative energy. Many times he said to me, quietly, like a confession, “I don’t sleep.” You mean you don’t sleep much, I asked? “No. I mean I don’t sleep.”

Like Warhol, he thrived on endless artistic creation, expressed in a multitude of media, and in all directions at once. When we met, he’d released a triumvirate of astounding records – impressive for any age, but at 58 truly miraculous – the absolute masterpiece of New York, which captured the madness of Reagan-era NYC better than any album; Songs Of Drella, a beautiful Warhol-inspired song cycle, and Magic And Loss. All contained songs about death, a subject from which he never shied. He was also busy mounting a gallery show of his photographs in Manhattan, and completing a musical called Time Rocker with Robert Wilson.

Like Warhol, he was forever diligent, always working on something serious, and yet never taking himself so seriously that he couldn’t laugh at the folly of it all, the delicate narcissism of artists desperately making art so the world wouldn’t forget them.

His disdain for most journalists was understandable, given how often they misportrayed him. Said to be solemn and surly, he was actually warm and gracious. Portrayed as darkly somber, he was sunny and very funny, with a deep appreciation of comic geniuses like Groucho Marx, whose letters he was reading when we met. Said to be arrogant and brutal, he was humble and warm. Though cognizant of his immeasurable influence on a vast range of songwriters – from Bowie to Strummer to Cobain – he refused to sing his own praises. When mentioning Warhol, for example, rather than boast of his own role in that exclusive cadre, he said that Andy felt lazy, and not productive enough. And more than anything – doing the work, getting it done, getting it into the world – was the aim.

Born in Brooklyn, 1942, he grew up in Long Island, the son of an accountant. From his teen years on, his one goal was to merge poetry and rock and roll. Unlike Dylan and others who did it with acoustic folk, Lou embraced rock and roll from the start and never let go. He was with the Velvet Underground for only five years, from ’65 to ’70, and from then on was solo. But always with a band – the equation he loved best: “two guitars, bass and drums.” He made masterpieces.

“I think they should build a statue to me,” he joked with a smile as I praised his greatness perhaps one too many times. More than anything, he said, he did it ‘cause he loved it. “Songwriting is phenomenal,” he said. “I get a major-league kick out of it. That’s the only reason I do it. I just want to have fun.”

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.