It was 1982, and I was three years old. My dad owned a car repair shop in Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, near where I grew up in Sevierville. My first life memory is listening to Alabama’s “Mountain Music” on an eight-track as he drove me to pre-school in his big white wrecker with Bill Watts Body Shop emblazoned on the side.

Being it was the early ’80s, “The Dukes of Hazzard” was the craze. The length of time it took to drive from our house to the bridge with the little dip in it was precisely the amount of time it took Alabama’s Randy Owen to get to the end of “Mountain Music,” where he yelled, “yee-haw,” just like Bo and Luke Duke in their car the General Lee. So, when my dad’s white wrecker flew over that little dip, we yelled yee-haw, too.

Who knew Dad was laying the groundwork for the rest of my life? At 45, I’m a CMA Award-winning journalist who has written about country music for 24 years for some of the largest and most respected outlets in the U.S.

I was with Alabama’s Randy Owen on Nov. 19 when BMI honored him with the Icon Award. That night, I watched Luke Bryan and Blake Shelton sing “Mountain Music” to Owen, who was in the audience. My dad died unexpectedly on Nov. 20. I listened to Owen sing “Mountain Music” a few days later in my car on the way to Dad’s service.

Videos by American Songwriter

My Dad Taught Me I Can Do Anything

My dad loved country music, The Beach Boys and The Hollies. A Sevierville native, Dad rode the school bus with Dolly Parton. He lived in a small two-bedroom house that smelled of cigarette smoke and exhaust fumes, with more garage bays than living space. He has his garage radio hotwired into the light switch, so WIVK, the Knoxville country station, starts playing when you flip the lights on. He walked through our Tennessee mountain home, singing the wrong words to country songs.

My Dad made me believe I could do anything I wanted to do –- by taking me to do anything I wanted to do. The Oak Ridge Boys was my first concert. Alabama was my second. After that, I was hooked. I mean, truthfully, by 8 years old, I was obsessed. I wrote fan letters to Owen and got an autographed picture back in the mail. I hung it over my bed.

I grew up so close to Dollywood that when the train whistle blew in the morning, it woke me up. In the ’90s, the park hosted contemporary country artists in its DP Celebrity Theater. I saved my birthday and Christmas money until concert tickets went on sale. Then, I’d take the morning off school and stand in line to buy tickets for my favorite artists – Exile, Sawyer Brown, and Restless Heart. (I’ve always loved bands.)

My Parents and My Band Broke Up The Same Year

Exile was another turning point for me. The members were so nice to me, a random little kid. They made me feel like they cared about me, so I cared about them. I called the local radio station WDLY daily for years to request Exile songs. When Exile celebrated 30 years as a band in 1993 at the Horse Park in Lexington, Kentucky, my mom took me to the show and family-friendly after-party. While there, the lead singer’s wife, Jamie Allen Martin, told me about the Recording Industry program at MTSU and Professor Beverly Keel. She said when I graduated high school, in more than four years, I should go to MTSU, major in Recording Industry, find Professor Keel, and tell her that Allen sent me. That’s what I did – and that’s why I’m here.

Within months of that show, my parents told me they were getting divorced. I also got a note from the fan club saying Exile was splitting up. (Exile is now back together, touring and recording music.)

I was devastated about both. My dad bought me an electric guitar and got me guitar lessons. The first songs I learned were “Mountain Music” and Exile’s “She’s a Miracle.” When Exile announced their final show eight hours from home in Owensboro, Kentucky, Dad took me. And when their bass player Sonny LeMaire played a songwriters’ night at Douglas Corner Café in Nashville, Dad drove me four hours to that. He didn’t do it because he just had to hear LeMaire sing “Nobody’s Talking” one more time. He did it because I had to hear it. Dad would say, “That’s my job! I’m your dad!”

It was my first of what must be hundreds of songwriters’ nights.

At 21, I Started Interviewing My Heroes

After I was old enough to go to shows alone, I don’t think my dad ever went again.

A few years later, I went to MTSU, majored in Recording Industry, and inadvertently got my first writing job. The university required me to take journalism classes, and when the local paper reached out to my journalism teacher and said they needed to hire someone, he sent them me. Until then, I didn’t even know I could write. I walked in the door at The Daily News Journal, and they said, “What do you like?”

When I said music, they told me to “write about that.” I made $6 an hour, but I was so proud. And so was my dad.

My first story was about Tom Wopat from “The Dukes of Hazzard,” starring locally in “Annie Get Your Gun.” My next was about Sawyer Brown being nominated for an award for their song “800 Pound Jesus.” At 21, I was interviewing my heroes –and I never stopped.

Seven years later, country singer Chris Young took me to meet Alabama’s Randy Owen on the set of Nashville Star. He told me not to embarrass him. When standing face-to-face with Owen, I burst into tears.

When Dolly Parton Kicked Me

I went from Murfreesboro’s Daily News Journal to Nashville’s Tennessean and USA Today. Then, I progressed to People, CMT, and American Songwriter. I’ve worked with almost everyone in country music over the years. One way or another, nearly all of them heard about my dad. I was backstage at the Grand Ole Opry once with Dolly Parton. She asked me if I liked her set. When I told her that “Tennessee Mountain Home” made me cry, she nudged me with her foot and said that had nothing to do with her. She said the song just reminded me of my daddy. She was probably right.

Dad just preferred to be at home in the Smoky Mountains. He’d occasionally come to Nashville, but not often. Sometimes, he helped me out with work from Sevierville. When the CMA Awards revealed nominations on television shows that aired first on the East Coast, and I was in a different time zone, I’d call Dad, and he’d lay his phone on the TV so I could hear them before anyone else in my time zone. He’d always say, “I’m your dad! That’s my job!”

I can’t remember how many stories I wrote from his couch or the number of celebrities I interviewed from his back deck while trying to find cell reception in the holler.

Dad just wanted me to be happy and be able to support myself and my kids. He didn’t care who I talked to or how close I got to fame. He was the most even-tempered person I ever met. But when I needed health insurance last year and one of the artists I had written about over the years helped me get it, Dad said, “Out of sight.” That was pretty high praise.

“That’s My Job”

I got the news he unexpectedly died as I was getting ready for the CMA Awards. Two cousins drove up from Sevierville to get me because they didn’t think I could make the trip alone.

I went home in a haze and made Dad’s arrangements. He didn’t want a funeral, but we had a graveside service. I posted about his passing on my Facebook page, but beyond that, we kept it pretty quiet as Dad said he wanted. When we arrived, dozens of people and a few flower arrangements were at the graveyard. I didn’t pay much attention. I just focused on holding myself together for my kids.

My 12-year-old son was on one side of me, and my 15-year-old daughter was on the other. My cousin, David Henry, did an outstanding job speaking before Dad was laid to rest in the family cemetery, recounting Dad’s common phrases, “That’s my job” and “That’s life.”

When it was over, David said, “I always listened to his music on the radio, but I didn’t expect him to send flowers to your dad’s funeral.”

I hadn’t looked and had no idea what or who David was talking about. I went to look at Dad’s flowers, and more than half of them were from artists I worked with. Dad had never met them, but they knew me and how much I loved my dad.

One of the cards – the one from the man who helped me get health insurance – said: “Honoring dads and heroes.”

Honoring Dads and Heroes

Losing Dad is the hardest thing my kids and I have endured. But through teaching me about country music, he prepared me for life—and for losing him. He led me to these songs – and a community – to carry me in his absence.

I didn’t realize until now that even “That’s my job” is a country music quote. Gary Burr wrote “That’s My Job” for Conway Twitty. The song is first a dad singing to his child.

Lyrics include: That’s my job, that’s what I do| Everything I do is because of you| To keep you safe with me| That’s my job, you see

Then the adult child says to his dad: I make my livin’ with words and rhymes and all this tragedy| Should go into my head and out instead as bits of poetry| But I say, “Daddy I’m so afraid| How will I go on with you gone this way?

I’ll search for that answer for the rest of my life.

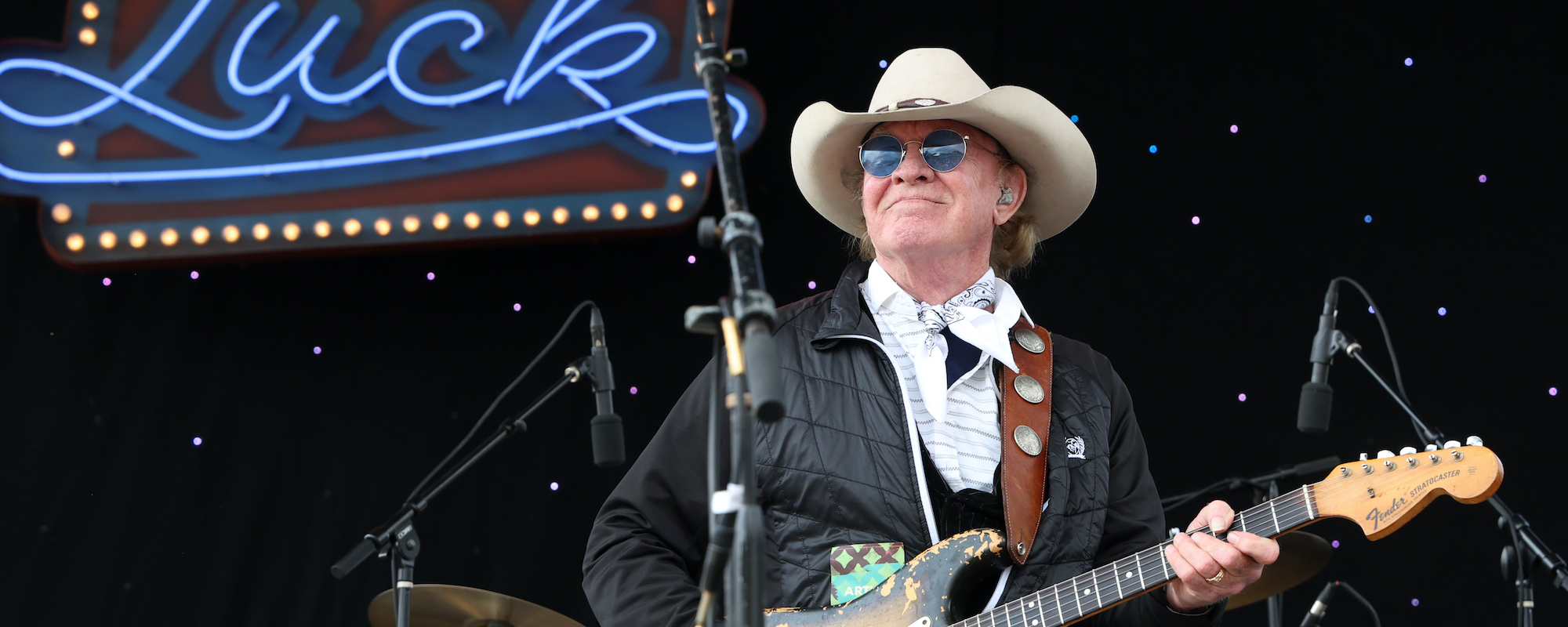

(Photo by Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images)

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.