With no crying over spilled milk in a sandbox

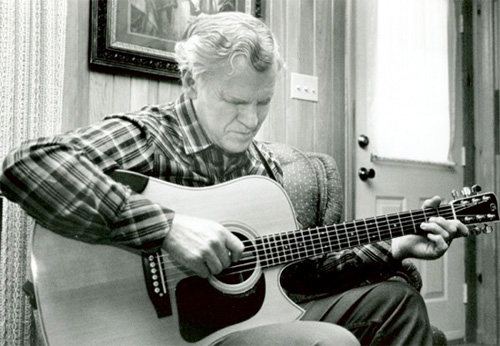

He used to tell people that had he not been blind, he probably wouldn’t ever have learned guitar, and would have most likely become a mechanic. Well, if that’s the case, thank God he was blind. The world’s a richer place because of it. If ever a musician symbolized transcending those obstacles that derail the journey, it’s Doc. The man couldn’t see. Not the way regular people do, anyway.

Videos by American Songwriter

Like other legendary blind musicians, it’s evident that Doc Watson’s lack of visual vision resulted in a miracle connection with music unlike that of a normal human. Whether he played a song of his own composition, or one he discovered written by somebody else, he always brought a purity of grace to the proceedings, a keen heartfelt focus, and a luminous touch that instilled everything he did with sweetness, joy and exultant soul.

Born Arthel Watson in Deep Gap, North Carolina on March 3, 1923, he took on Doc when an audience member suggested it as more suitable than Arthel. An eye infection robbed his eye-sight when he was an infant. Told later in life he could possibly regain 5 percent vision in one eye, he declined: “I said there’s no use crying over a glass of milk spilled in a sand box,” he remembered. When asked how he managed without sight, he said, “I can see with my feet and my hands and my ears.”

Doc died on May 29 in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. He was 89. Because of his astounding guitar playing, as well as being one of folk music’s greatest singers and interpreters of songs, his own greatness as a songwriter is often overlooked. Like Pete Seeger, who wrote many classics himself among all the classics he performs, Doc was always dedicated to the spirit of folk music, of discovering, dusting off, and inhabiting great songs written by others. Like Pete, he always embraced the “folk process” of finding great old songs and making them his own.

He was a genius of the folk process. His blindness and inability to write anything down helped develop his remarkable sense of recall, which served him well. When Elizabeth Cotten, for example, sang him her classic “Freight Train” – including several verses she’d never performed – he remembered it precisely. Many long presumed the “pickle me in alcohol” verse that he sings in his famous rendition of the song was the spontaneous product of Doc’s imagination. Not so.

“I heard Elizabeth [Cotten] sing that [verse],” Doc said. “She was the kind of person who, if you got to know her, you didn’t forget her. And what she sang, it just claimed a little corner in your thinking and stayed there.”

So trying to hone in on Doc the songwriter is tricky, as it isn’t easy to calculate where his songs began. There are some 156 songs registered to him with BMI, and the bulk of these are instrumentals, while untold others are adaptations. It’s much like the body of work left by Woody Guthrie, whose thousands of songs have a remarkable diversity of origin.

It didn’t matter much to Doc, as it didn’t to Woody, if he started the song himself or if someone else did. It didn’t even matter who finished them. What mattered was making the song come alive. Who could play the old fiddle-tune “Black Mountain Rag,” for example, with more soul, whimsy and fluid grace than Doc? How he’d soar through the tune, playing the fiddle, banjo, mandolin and guitar parts all simultaneously and remarkable. It didn’t matter that he didn’t write the song.

He was no folk elitist, focused only on the music of the past. He was happy to do a brand new song, if it was great. As Pete sang Dylan’s songs, Doc sang the songs of Townes Van Zandt, Dan Fogelberg, Tom Paxton and others.

He delighted in being a folklorist as much as a folksinger, and enjoyed edifying his audiences with details about the abundance of treasures he’d discovered. He credited his pal Ralph Rinzler, a Smithsonian musicologist who discovered him and encouraged him to put down his electric guitar to play acoustic, for encouraging him to talk about his songs. “I love to talk about them,” Doc said. “Why not talk about the music you play? It makes sense. People seem to enjoy it.”

In the clamor of modern times, his own songs resound with the timeless calm of traditionals. “Your Long Journey,” a reflection on death that he wrote with his wife Rosa Lee, has the sound of centuries in it. Emmylou Harris recorded a famously haunting rendition of this, as did Robert Plant and Allison Krause on their duets album.

Death was not a subject he shied away from, either in song or conversation. In a 2011 interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer, writer Dan DeLuca asked about his health, and he said that, for an 88-year old man, it was “exceptionally good.” All his stress, he said, concerned his wife’s failing health. But as for himself, he had no fear of following his long journey to the end.

“If I have to leave pretty soon,” he said, “I’ve fixed it to be ready to go. I sit in my rocking chair in my family room and listen to Randy Travis and his song ‘Doctor Jesus.’”

There are so many out there

Do you think you could work me in?

I need you to mend my heart and save my soul.

“Now you know how I think,” Watson said. “I’m not afraid to die, son.”

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.