This is not the story of what actually happened. This is the story of what might have happened.

Videos by American Songwriter

CHAPTER ONE: BURBANK, CALIFORNIA, JULY 22, 1978

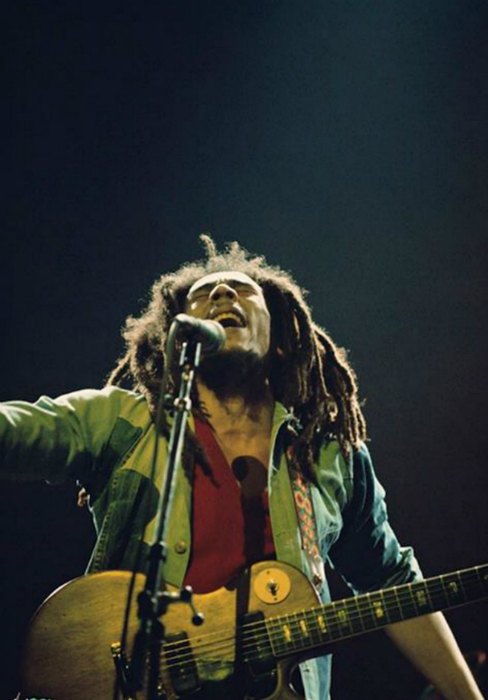

Bob Marley was relaxing in his dressing room after his show at the Starlight Bowl Amphitheater in Burbank, California, on July 22, 1978. The room was full of chatter in his native Jamaican patois, as his musicians and crew passed around a snowcone-shaped spliff and munched on the spread of “ital” health food. But Marley himself , still in his stage outfit of denim and a green T-shirt, was lost in his own thoughts, staring at the pinhole acoustic tiles overhead as if they were stars.

His eyes widened, though, when his manager whispered in his ear. Bob nodded eagerly, and the manager scampered away and returned with two Americans, the first leading the second, who was blind. Bob recognized them as Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, because he had been the opening act when each of them had headlined a concert in Kingston in 1974 and 1975. Now there were hugs, pleasantries, reminiscences and tokes on the circulating cigarette.

“I still remember that show in Kingston,” Stevie said, grinning and rolling his head with joy. “You guys came out at the end and we played ‘I Shot the Sheriff’ and ‘Boogie On, Reggae Woman’ together.”

“Yeh, mon,’ Bob replied. “That the last time Peter and Bunny and I sing on same stage.”

“I would have killed to hear that,” said Marvin, sprawled on a couch in his tailored gray suit. Inspired by the comment, Bob told his bandmates to get their instruments and set them up in the dressing room. An electric piano was set up with a small rehearsal amp in front of Stevie, who was still wearing his wraparound shades.

Bob had his Ovation acoustic guitar; Aston “Family Man” Barrett plugged his bass into a small amp, while his younger brother Carlton “Carly” Barrett applied his drum sticks to a tambourine. With just those four instruments, they played “I Shot the Sheriff” and “Boogie On, Reggae Woman” before pushing on to “Lively Up Yourself” and “Superstition.” All the other musicians, crew and visitors crowded in a ring around these four.

After much pleading, Marvin agreed to sing “What’s Going On.” When Bob sang the same song in a heavy Jamaican accent (“Tell I what goin’ on”) and a push-pull reggae beat, Marvin doubled over with appreciative laughter.

“Yeh, mon,” Bob said. “We know all them songs from the States. Fats Domino. Curtis Mayfield. Ja-a-a-a-ames Brown! That’s how I learn to go, ‘Uh!’” With that he sang, “Get uh-p, stand uh-p! Stand uh-p for your rights.”

“Your songs remind me of Detroit in 1961,” Marvin mused, “back when the music was rough and rowdy, coming right off the street corner, off the floor of the car factory, John Lee Hooker, Reverend Franklin, Wilson Pickett, doo-wop, hand-claps, dirty guitars and sweet harmonies. I miss that.” Stevie laughed and started playing and singing Marvin’s first top-10 hit, “Pride and Joy,” and Bob, who knew the lyrics perfectly, joined right in, as did Marvin himself.

A few hours later, the party had moved to the Hilton Hotel; the other musicians had peeled off to their own rooms with their new-found ladies, and Bob, Stevie and Marvin found themselves the sole survivors. That’s when Stevie popped out the question he’d been reluctant to ask: “Bob, are you OK? I hear you’ve been sick.”

Bob hesitated. He stared at the two men he’d heard coming through the big-cabinet speakers at the DJ sound-system shows of his youth. Impulsively, he blurted out, “Yeh, mon, they say I got the cancer in my toe. They wanna cut it off, but I don’t wanna. In our religion, you’re not supposed to cut the body. And I don’t want to be a cripple. How’m I gonna dance on stage? How’m I gonna kick the football?”

“Hey, man,” Marvin barked at him, “you don’t wanna fuck around with that cancer. That shit got into my cousin; he did nothin’ ‘bout it, and, bang! he was dead. Don’t mousey-mouse around—jump on that motherfucker and kill it right now.”

“But ain’t natural,” Bob complained, “all that surgery, those chemicals and radiation. I a Rasta man, and my body sacred.”

“Yo body gonna be dead if you don’t get your ass in gear,” Marvin retorted.

“Look at it this way, Bob,” Stevie intervened. “Is the electric guitar natural? Is the airplane natural? Is the hotel elevator natural? Are the stage lights and PA system natural? You use all these unnatural things to spread your natural-mystic music to the world. This is just one more thing like that.

“You have a rare gift, but with that gift comes responsibility. And the biggest responsibility is to stay healthy so you can keep doing your work. A lot of brothers and sisters can’t express their feelings the way you can, and they need you around to do that for them.”

“I don’t know,” Bob said. “I think about it.”

The conversation went on for another hour. Bob’s 1978 tour wound up on August 5 in Miami, where his mother was living. Bob stayed an extra week to talk things over with his family.

On Monday, August 14, Marley issued a public statement. He was suspending all recording and live performances for a year to resolve his health problems. On Wednesday, he checked into the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City.

CHAPTER TWO: KINGSTON, JAMAICA, MARCH 8, 1980

Scalpers were asking 100 pounds or more for tickets to the “Welcome Home, Bob Marley, Concert” at the National Heroes Park in Kingston on Saturday, March 8, 1980. These were prices only American and European tourists could pay, and the residents of Trench Town weren’t happy. They were seething if they lacked a ticket and torn by indecision if they had one. Sell or keep? Keep or sell?

No one knew what to expect. The singer had been in a New York hospital from late summer of 1978 to late summer of 1979. Some said he would be in a wheelchair for the rest of his life. Some said he was jogging two miles a day. Some said he had become a “crazy baldhead”; some said his dreadlocks were as long as ever. Some had claimed that he had lost his voice and would never sing again. That rumor, at least, was quashed when the new album by Bob Marley & the Wailers, Survival, was released on February 26. But many said it wasn’t as good as his previous records.

Those with tickets waited in long lines to enter the soccer stadium. Because Kingston was suffering from another spike in gang violence, each person was being frisked. Eventually they were seated, and as the sun went down, the stadium lights came up. The first set showcased the Melody Makers, a vocal quartet featuring four of Bob’s children: Ziggy, Stephen, Sharon and Cedella. They played four songs, including their recent single, “Children Playing in the Streets,” written by their father. The second set featured the I-Threes—Rita Marley, Judy Mowatt and Marcia Griffith—who also did four songs.

Finally, the moment came. Colored spotlights swept the stage as the Wailers began the grooving riff to “Jammin’” A few minutes later, Bob himself appeared. He was neither bald nor dreadlocked but sported the bushy afro of his early career. He didn’t jog onto the stage as in earlier days, but neither did he limp. He walked deliberately up to the mic and grabbed it confidently. “We’re jammin’,” he sang. “Don’t think that jammin’ is a thing of the past; we’re jammin’, and I hope this jam is gonna last.”

After the fourth song, “Trenchtown Rock,” he waved the band and audience quiet and spoke softly and earnestly. “I and I come through a mighty trial,” he told the crowd. “The cancer try to eat I up, but I eat the cancer up. The American doctor say I’m ital. The Rasta bush doctor say I’m ital. I and I going to live a long time and make much music.”

The band celebrated the announcement with the bouncy introduction to “Lively Up Yourself,” and the audience, now standing, did just that, swaying and rocking in place. After another hour, when Bob returned to the stage for the encore, he said, “I and I bring no politicians to the stage tonight.” This was an obvious reference to the 1978 show in this same venue when he had brought Prime Minister Michael Manley and his bitter rival Edward Seaga on stage and urged them to shake hands. It was a hopeful moment, but the optimism didn’t last long.

“On this night,” Bob continues, “I and I bring you two true warriors for justice: Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer.” The crowd erupted in a frenzy. No one ever thought they’d ever see these three original Wailers on the same stage again. Bob’s untucked denim shirt was open over his red T-shirt. Bunny had a red-green-and-gold scarf draped around his neck and a matching knitted tam on his head. Peter, a full foot taller than his partners, wore an open khaki shirt over a tan tank top.

Each man sang lead on one song he had written: Bob on “Stir It Up,” Bunny on “Riding High,” and Peter on “Stop That Train.” They exited to a thunderous yelps and pounding on chairs, only to return for one more song. Blending their three voices, as if they were still imitating the Impressions in 1964, they sang their first #1 Jamaican hit, “Simmer Down.” It all went so well, that afterward, Bob invited Peter and Bunny to come along for his upcoming tour to Africa and Europe, and his erstwhile partners readily agreed.

But when the first rehearsal at the Hope Road house was scheduled to begin three days later, there was no sign of Bunny and Peter. An hour later, while Bob and the band were running through “Zimbabwe,” written by Bob for their upcoming show at that African nation’s Independence Day ceremony, Bunny and Peter shuffled into the room.

The music sputtered to a halt, and Bob said, “Better late than never. Are you ready to get to work?”

“No, mon,” Peter said, “I and I not going to work for you and Mr. Chris Whitehell.” This was a reference to Chris Blackwell, the founder of Island Records and the co-producer of Bob’s records since 1973. “I and I not gonna fly all over this world to chase the fame and money of the white man. I and I gonna stay right here on this island, the true source of inspiration.”

Bob’s head drooped to his chest. These were the same arguments he had heard in 1974 when Peter and Bunny had left the band. They didn’t want to fly; they didn’t want to tour; they didn’t want to leave the comfort zone of the people and places they knew so well.

“Jah say I and I are destined to go home to Africa,” Bob said. “The door is open now to do that. I and I can walk through that door and get to know the Motherland, but now you want to slam that door shut. What sense is that?”

“It’s that White man’s blood in your veins that makes you say that,” retorted Peter, the redness of his eyes a measure of just how stoned he was. “You don’t feel at home in your own land with your own people, so you are cursed to wander the earth.”

“Jah say this music is not just for Jamaica,” Bob added. “Jah say this is a gift for all mankind. Jah say we can teach mankind many things if we try. Jah say mankind can teach us many things if we let it.”

“Bob,” interposed Bunny, the quietest and calmest of the trio, “I got nothing against you, your father or your plans. That’s you and that’s right for you. But I am Bunny, and I’m unhappy on the aeroplane and in the hotel. How can I make happy music if I’m unhappy? I’m sorry.”

The two visitors turned and walked out of the house. Bob and his band continued the rehearsal. A month later they were in Harare (formerly known as Salisbury), the African capital, to watch the flag of British Rhodesia come down and the flag of an independent Zimbabwe go up. They had warmed up the crowd before the ceremony with a free concert.

But two-thirds of the way through the set, Robert Mugabe’s police had fired tear gas at locals trying to get in to hear the music. When the gas drifted into Rufaro Stadium and onto the stage, the concert was halted for 45 minutes. Bob and the Wailer returned to finish the set, but it was not the happy occasion he’d been hoping for. As he wiped his burning eyes with a wet cloth, he realized that even in the Motherland, even in an independent, black-ruled nation, the battle between the haves and the have-nots went on. Who was right? Him or Peter?

CHAPTER THREE: LONDON, ENGLAND, MAY 1, 1981

The Specials were getting ready to go on stage at the London’s Rainbow Theatre on May Day in 1981. Group founder Jerry Dammers and lead singer Terry Hall were sniping at each other, as usual. This time the argument was over the set list, with Dammers wanting more new, unrecorded songs, and Hall wanting more covers that reinforced their roots in Jamaica’s ska music of the ‘70s. The last of the opening acts was finishing up, and they had to make some decisions.

Just then, the road manager burst into the dressing, out of breath and spewing gibberish. Terry handed him a beer so he would calm down. “You’ll never guess who’s in the house,” the manager finally managed to blurt out. “Bob Marley.” Both jaws on the feuding musicians dropped simultaneously, and they said in unison, “The Bob Marley?” “Yeah, the Bob Marley.” “Whatever you do,” Jerry stammered, “get him to come back after our set. Don’t let him leave the venue.”

This meant a lot more to the sextet than the time Paul McCartney had dropped in on them. Their whole aesthetic was built on the brisk, chipper dance beat of the Wailers’ early ska records and the fierce political lyrics of the Wailers’ later reggae records. It was if a boxing club were being visited by Muhammad Ali. The Specials’ two Black members, toaster Neville Staple and guitarist Lynval Golding, were especially stoked, but all six were excited. Jerry and Terry put aside their differences, and the musicians went out and put on the show of their lives.

The encore songs, Toots & the Maytals’ “Monkey Man” and Dandy Livingstone’s “A Message to You, Rudy,” were a thrill, but the evening’s true climax came when the road manager entered the dressing room, ushering in a slender man with a face the Specials had seen on dozens of record sleeves. There was a moment of stunned silence, and the reticent visitor wasn’t going to help his hosts out. Then a hundred question burst out as if a dam had opened, as if releasing the hidden fanboy in them all.

What are you doing in England? How long are you here for? How did you hear about us? What did you think? Did you like it? Do you want a beer? Do you want some vegetables? Could you hear OK? Could you see OK? How’s your health? What are you working on?

“I living in London now,” Bob said, when the babbling subsided. “Too much shooting in Jamaica. I stay here until the picture become clear. I hear about the new ska music in England, and I have to check it out. And I like it. I always wonder why ska was dead and buried so quick. That music had much more to say. And now you are saying it.”

Over the next few months, Bob would show up at ska shows all over London. It might be a show by Selecter, the Beat, Madness or the Specials, and there would be Bob, suddenly appearing like a ghost from who knows where. As he got to know the musicians, he started to hang out with them at their rehearsals and studio sessions. During the Specials’ recording of the single, “Ghost Town,” sat behind the engineer in the control booth and nodded along without saying much. He only suggested that the line, “No one to be found in this country,” be changed to “No job to be found in this country.”

Despite his quiet demeanor, he was absorbing everything he saw and heard. In October, he made an appointment with his producer Chris Blackwell. With a black guitar case in hand, Bob strode into Island Records’ wood-paneled London office. Without saying a thing, he unlatched the case, lifted out an acoustic guitar and played six new songs in a row. Each one had a quick, skipping beat and short, crisp bursts of words.

“Oh, my god,” Chris cried. “Ska! Back to your roots. It’s the right sound for the right time. This sounds like those early Studio One singles by you, Peter and Bunny, but the lyrics sound like they’re coming from a man, not a boy. How soon do you want to go into the studio?”

“As soon as you can fly the band in,” Bob responded.

When the resulting album, Skatisfaction, was released on March 16, 1982, it shocked critics and fans alike with its abrupt change in sound and feel, much as Bob Dylan’s turn to country music had. The die-hard reggae fans denounced it as a commercial sell-out, but the younger fans of England’s “Two-Tone Ska” movement embraced it as a validation of everything they’d been doing.

With its brisker, crisper rhythm, there was little room for Bob’s recent lyrics of political and religious analysis nor for his slow-hymn melodies. Instead the emphasis was on compact catchphrases that became hypnotic with the bouncy beat. A few songs were recycled from his earliest recordings—“Judge Not,” “Put It On” and “Simmer Down”—only with better singing and playing this time. Some of the newly written songs, such as “Don’t Block Me (I’m Coming Through)” and “Standing on a Flimsy Ladder,” were obviously political. Others were more like the early ska singles in Jamaica, obsessed with love and lust.

The one with the catchiest melody was “Lookin’ for a Rasta Girl.” When Island released it as a single, it quickly went to the top of the British charts, and the chorus seemed to be coming out of every boom box on every corner: “Lookin’ for a woman who can roll big spliffs, lookin’ for a woman with a righteous kiss, lookin’ for a woman who can change the world, lookin’ for a Rasta girl.”

Meanwhile, the Specials had fallen apart soon after their own single, “Ghost Town,” had topped the charts a year earlier. But Dammers and Hall, each in his separate flat, had to wonder what might have been when they heard their hero sing, “Lookin’ for her at the demonstration, lookin’ for her at the railway station, lookin’ for her in the jungle and desert, lookin’ for her at the Specials concert.”

CHAPTER FOUR: JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA, DECEMBER 15, 1993

Bob Marley arrived from Kingston at Jan Smuts International Airport in Johannesburg, South Africa, on December 13, 1993, the same day that Nelson Mandela flew back from Oslo after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize. The two men were about to meet for the first time. Nelson was running to become the first Black president of his nation. Bob was running from his past, searching for answers.

Bob’s career had been thriving over the past decade. He had followed up 1982’s Skatisfaction with 1984’s Confrontation (with its U.K. #4 single “Buffalo Soldier”). His 1986 collaboration with Stevie Wonder, Master Blaster, had yielded the #9 U.S. single, “Nobody Wins Unless Everybody Wins,” and a sold-out tour with Wonder of outdoor stadiums in North America and Europe. That had been followed by 1990’s Firelight: MTV Unplugged.

Bob was buoyed by his commercial and artistic success over these years, but he worried he was losing touch with his political and spiritual message. He knew where he needed to be: in South Africa. That nation was on the cusp of finally giving its majority Black population self-determination after decades of struggle. And it seemed like they might do it without succumbing to the long-feared Civil War. Bob knew he had to be a part of that.

Island Records had rented a renovated house for Bob in Soweto, the segregated Black area of Johannesburg. The label had also arranged for an appointment between Bob and Nelson at the headquarters of the African National Congress on the 15th. When he arrived, he was led through the beehive of telephones, election posters, typewriters and shouting workers on the first floor to the relative calm of Nelson’s office on the third floor. The Nobel Laureate rose from behind his desk and walked to meet Bob halfway, grasping the visitor’s right hand in both of his.

The 75-year-old man in the pinstripe suit bore a modest afro that was graying at the temples. His face wore the weariness of the years on a prison island, but his smile seemed warm and genuine. Bob, his dreadlocks spilling over his shoulder blades and his narrow eyes watching everything closely, was surprised.

“Maybe you don’t know how much you and your music have meant to us in Africa,” Nelson said. “But when we suffered defeats—and we had plenty—your songs helped us to keep going. And now, when we’re so close to victory, when there’s still so many ways things can go wrong, we need you more than ever. How long are you planning to stay here?”

“As long as it takes,” Bob said simply.

“Good, good,” said Nelson. “We don’t need you to march in demonstrations or make speeches. We have many who can do that. We need someone who can speak to the ordinary man or woman, the cobbler or the nurse, the porter or the midwife, the vendor or the teacher, someone who can speak to them not in the dry speech of slogans and ideas but through the damp feeling of music, someone who can keep them hopeful when things look bleak.”

“I will do whatever you ask,” Bob replied.

“Let me explain,” Nelson continued, “the biggest threat to our movement is not the hatred of our enemies; we expect that and can’t alter that. The biggest threat is the despair of our allies. Because when good people give up, bad people win. If you could sing your old songs, maybe write some new ones, maybe at some concerts, maybe on a record, that will be worth a hundred marches and a thousand speeches. Can you do that?”

“I can do that.”

“Good. I will assign you two bodyguards so you can walk about our community and see the situation for yourself. Then maybe you can come back and ask me some questions.”

“I like that.”

Over the next five months, Bob walked the street of Soweto, seeing the kind of poverty and police presence that reminded him of his adolescence in Kingston. When he found someone who had interesting things to say, Bob would bring that person back to the rented house for long conversations, “reasonings,” as the Rastas say. And in the evening, after dinner, he would sit alone with his acoustic guitar and try to turn what he was learning into new songs. And every few weeks he would visit Nelson again.

Whenever he was asked, he would perform at a church or trade union hall or atop a flatbed truck. Gradually he worked some of his new songs into his set. He began to get together with some of the city’s top musicians, those who had played on Paul Simon’s Graceland album or on the records by Mahlathini, the Mahotella Queens, Johnny Clegg or Dollar Brand.

In February, they went into a studio to record Bob’s next album, Wheels. The township jive favored by these players was not so different from the syncopation of Jamaican reggae, and the singer found a middle ground with his new collaborators. The songs recast the conflicts in South Africa in fable-like terms that could apply to any situation in any country where the few dominate the many.

But the album was named after its centerpiece song, “Wheels Spinning Round,” the song that became the anthem for Nelson’s election campaign, a song that people would sing at election rallies, on city buses, on street corners. It was the first Bob Marley record to feature an accordion, but that bleating squeezebox was perfect for the bouncing, celebratory chorus and its sing-along melody.

“Wheels spinning round and round,” crowds would sing together, “whole wide world turned upside down. The last shall be first; the first shall be last. What’s happening now will soon be the past.” The voices seemed to rise in excitement and pitch when they got to the bridge: “Nelson Mandela’s shadow is large. You locked him up; now he’s in charge.”

On April 27, 1994, the African National Congress won the vote with 63% of the vote, and Nelson Mandela became president. Bob Marley played “Wheels Spinning Round” at the inauguration ceremony. This time there was no tear gas and no regrets.

CHAPTER FIVE: MONTEGO BAY, JAMAICA, APRIL 17, 2002

Bob Marley’s cancer came back in 2000, and this time there was nothing the doctors could do to stop it. His wife Rita and her daughter Sharon were distraught, but Bob was philosophical. Because Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder had convinced him to get treatment in 1980, Bob had enjoyed 20 additional years of life and productivity.

He was then 55, and he’d had the chance to see his kids grow up. He’d been able to make an album with his kids (1998’s Youth ). He’d lived in England, the United States and South Africa, and he’d been able to make important music in each place. He’d survived assassination attempts in Jamaica in 1976, 1981 and 1997. He’d sold millions of records and played to millions of listeners on every continent but Antarctica. He had nothing to complain about.

After the last attempt to shoot him, Bob had moved out of Kingston and had bought a place overlooking the Caribbean near Montego Bay, just down the road from Johnny Cash’s house. His old friend Peter Tosh had died in a home robbery in 1987, but his boyhood pal Bunny “Wailer” Livingston was still around and had moved to Montego Bay to be near Bob. After their many quarrels over the years, both Bob and Rita had mellowed and grown comfortable with each other. And so Bob started to write some of the tenderest love songs of his career.

Slowly but surely, at the leisurely pace of two old men, Bob and Bunny were working on a new album, produced by Bob’s oldest son Ziggy. It was titled Farewell, and it had the autumnal feel of a departure. Carlton Barrett’s bass was electric, but Bob’s guitar was acoustic and so was Ziggy’s piano. Aston Barrett’s drum kit was small, and that was it.

The central song was called “The Circle of Your Arms,” the confession of a warrior for justice who’s now willing to turn that job over to a new generation. It opened with Bob strumming a series of pretty chords over the Barrett brothers’ minimalist groove. Over Ziggy’s gospel piano chords, Bob sang, “ My fighting days are over; I’ll man the lines no more. I’m proud of all my battles, but my knitted bones are sore. There’s a time for struggle, and there’s a time for rest. There’s a time for lying down with the one you love the best.”

As the melody opened up on the chorus, Bunny and Rita added their voices in harmony. “I will go down to the ocean,” Bob sang; “I will wade into the waves. I will rise up from the water, clean if not quite saved. I will climb the stony beach; I will cross the neighbor’s farm. I will climb into your bed, into the circle of your arms.”

Bob died peacefully in his favorite chair, on the veranda of his home overlooking the sea, on April 17, 2002.

Lyrics for “Lookin’ for a Rasta Girl,” “Wheels Spinning Round” and “The Circle of Your Arms” copyright © 2020 by Geoffrey Himes.

Photo by Bill Fairs on Unsplash

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.