Videos by American Songwriter

The late, revered rock critic Paul Nelson got to know many of his subjects intimately. Whether it was Leonard Cohen or Warren Zevon, Nelson’s aesthetic tastes and insistence on integrity endeared him to many of the artists he wrote about.

Says Bruce Springsteen: “He is somebody who played a very essential part in that creative moment when I was there trying to establish what I was doing and what I wanted our band to be about.”

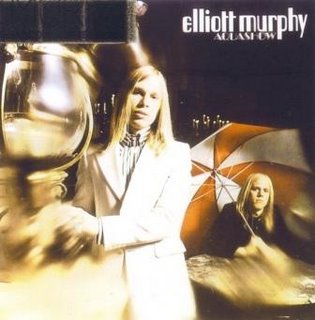

In this exclusive excerpt from Everything’s An Afterthought: The Life And Writings Of Paul Nelson, a new book which examines his work and influence, author Kevin Avery details Nelson’s relationship with singer-songwriter Elliot Murphy, one of the many artists to be tagged the “New Dylan” by the excitable rock press.

Everything Is An Afterthought is due November 21 from Fantographic Books and is available for pre-order at Amazon.com.

* * * *

Elliott Murphy was Paul Nelson’s rock & roll dream incarnate. The singer-songwriter’s music was rooted as much in literary traditions—F. Scott Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and detective fiction—and films as it was Bo Diddley and Bob Dylan. The two men met in Paul’s office at Mercury in January of 1973.

“He was the exact opposite of what I thought a record company guy was going to be like,” Murphy remembers, “not a jive bone in his body.” As his demo tape played, he thought he saw a subtle reaction behind the dark glasses. “He just gave some kind of grunt that was more emphatic than his negative grunt. When he really loved something he’d take an extra puff on his Sherman and that was about it.”

Paul’s professional courtship of the twenty-three-year-old Murphy extended beyond the two-Coke lunches at La Strada. Paul supplied him with early Dylan bootlegs and, with special import, presented him with the just released debut album by another East Coast troubadour. Paul told him to listen carefully. Bruce Springsteen’s Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. immediately influenced Murphy. “Not so much in my own approach to music, but it gave me so much confidence.” Paul soon took Murphy to see Springsteen play Max’s Kansas City and, after the show, introduced them.

At Paul’s spartan apartment, where the myriad of books and LPs created an orbit around the bed, TV, stereo, and the IBM Selectric typewriter situated on a board suspended between two sawhorse legs, Murphy noticed footprints low on the wall where Paul planted his feet and did one hundred sit-ups every day. Paul pulled open a drawer and took out two handguns, a .357 Magnum and a snub-nosed .38. Paul said he wanted to write a detective novel and, if he were going to write about guns, he needed to know how they felt in his hand.

Despite Paul’s enthusiasm, the Mercury hierarchy remained lukewarm about Murphy, offering only a conservative $5,000 advance with a minimal royalty. Underwhelmed, Murphy said he’d think about it. By the next day, he and his brother/bandmate Matthew secured a $10,000 offer from Polydor. Murphy took the counterbid back to Paul, whose boss Charlie Fach refused to go higher than $7,500.

Murphy asked Paul what to do. “I felt some kind of allegiance to him because he had really discovered me, so to speak. He became my mentor.” Paul told him to accept the Polydor deal. If things didn’t work out for the New York Dolls, who hadn’t yet signed with Mercury (they would the following week), then Paul’s days were numbered. “He said that if he wasn’t there, then nothing would happen with me and it would just be a contract I’d be trying to get out of.”

Murphy signed with Polydor and recorded his debut album, Aquashow. Paul dropped in on several of the sessions on the tenth floor of Record Plant East, where, down on the first floor, the Dolls were recording their first LP. Aquashow was released in November and Paul wrote about it a couple of months later. A budding singer-songwriter (from Long Island or anywhere else) couldn’t have hoped for a better coming out: Paul’s eloquent rave landed on the opening spread of the record-review section, right beside a critique of Springsteen’s sophomore effort, The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle. And while Paul went out of his way to downplay any easy comparisons to Bob Dylan, a careless pull quote subverted his efforts: his line, “Aquashow is easily the best Dylan LP since John Wesley Harding,” was turned into the title “He’s the Best Dylan Since 1968,” thereby sealing Murphy’s fate as the next “new Dylan.” Nevertheless, what Paul wrote about Aquashow was as personal and heartfelt as Murphy’s creation of it. When the singer sang that he was “Waiting for some dream lover like a Great Gatsby,” it might as well have been Paul behind the microphone.

Eighteen months of wrestling with creative and corporate demons passed before Murphy’s next album came out, 1975’s Lost Generation. Paul, whose own professional wrestling match had ended when he left Mercury in January and returned to freelancing, stayed in touch throughout. At one point he approached Murphy about serving as his manager. “It would have been pretty strange, Bruce Springsteen managed by Jon Landau and me managed by Paul Nelson. I just don’t think at that point I could imagine Paul doing the business.”

If Paul had, in writing about Aquashow, confessed his rock & roll ideal, his review of Lost Generation identified the desires and devils at the heart of the artist—all artists, not just Murphy—and at the same time embraced them as his own. One of Paul’s most obliquely confessional, academic, and, with its miasmic array of references and quotations, challenging works, it’s all about “the dangers that can befall those who are hung up on heroes.”

“I have often been accused of being the critic most friendly to Elliott Murphy’s work,” Paul’s review of Elliott Murphy’s third LP, 1976’s Night Lights, began, “a charge to which I happily plead guilty. …

Over at Rolling Stone, Dave Marsh wrote:

In 1973 and 1974 it seemed to many of us in New York that it was a tossup whether Bruce Springsteen, the native poet of the mean streets, or Elliott Murphy, the slumming suburbanite with the ironic eye, would become a national hero first. Well, we all know how that turned out …

Paul’s 1977 review of Just a Story from America was short and not so sweet. Whereas his expansive notices for the first three albums had each clocked in at over 1,200 words, this time around he said what he had to say in a fourth of that. Straining to call the record one of the year’s best and ending with a lovely coda, his sense of disappointment and regret was palpable.

Chris Connelly: “Part of how you be a good critic is you’re willing to be touched, you’re willing for the magic to strike you. What was so poignant about Paul was that he kept his heart open like that. If it means that an artist who didn’t fulfill his promise got to him, well, that’s the way it goes. That’s cool. That speaks to his openness.”

Murphy: “I never thought Paul would write just a glowing review about everything I did. I knew his integrity was completely solid. If he didn’t like something he would tell me and he would write about it, if he wanted to.”

Regarding Paul’s relationship between himself and the artists with whom he became friends, Fred Schruers says, “He wanted their respect and he didn’t want them to disappoint him, that’s for sure. Likewise, he didn’t want to disappoint them. So he would write the piece. If he had to damn somebody who strayed into something he felt was artistically unproductive, he would write that story, but it was painful for him.”

When Paul interviewed Murphy for the article “Elliott Murphy’s Career: This Side of Paradox,” his review of Just a Story from America hadn’t yet run. “I was aware that Paul had reservations about the album and probably about what was happening to me personally, as well. I was addicted to cocaine, stopped touring, broke up my marriage, gave all my money to the IRS, left my management, and generally did everything I could to fuck up my career.”

Though Paul never wrote about Elliott Murphy again, they remained in touch. Murphy fondly recalls one time in Paul’s office in 1980 when the two friends cocked their heads and strained their ears to decipher the lyrics of Joy Division’s newest single, “Love Will Tear Us Apart.” Paul thought the song was “magic.” “His taste was so much more eclectic than you would imagine for the founder of The Little Sandy Review, and his office was so much messier than you could imagine for a writer who wrote such architecturally perfect paragraphs.”

The Eighties proved difficult for both men. After Paul resigned from Rolling Stone, he occasionally met Murphy for lunch at Jackson Hole. He still ordered two Cokes but, in place of the veal piccata that he’d enjoyed during better times at La Strada, now he ordered a hamburger.

“It was hard to reach out to Paul. You knew he was in trouble, but he was never needy in that way. When he needed money, he just asked me if I wanted to buy his F. Scott Fitzgerald first editions; he didn’t ask if I could loan him money.” He still has Paul’s copy of The Great Gatsby. “I didn’t want him to sell it to somebody else because he’s the one who connected Gatsby to rock & roll for me.”

One October evening in 1985, Paul met up with William MacAdams at Tramps on West Twenty-First Street to see Murphy perform. Both men arrived with heavy hearts. Earlier that day their hero Orson Welles had died. It was a bad night for Murphy, too, and having Paul there to witness it in an audience of only twenty-five or so made it even worse.

After the concert, Paul and Murphy lingered and danced around their goodbyes. They talked about Bruce Springsteen, but not about how huge a success he’d become. They reminisced about their old days together when

Paul had reviewed Aquashow and Lost Generation, and Murphy “thought it was all going to be okay.” Pausing at the door, looking just as he had when Murphy first set eyes on him a dozen years earlier—same glasses, hat, moustache, a smoldering Nat Sherman stuck between his lips—Paul looked back at Murphy and said, “Well, it could have gone either way.” It was a farewell scene worthy of Raymond Chandler.

After Murphy moved to Paris in 1990, he paid tribute to Paul in the liner notes of a CD reissue of Aquashow. “I sent him a CD, but I don’t know if he ever saw it.”

“In some way, I always felt that I let Paul down, that I didn’t keep my eye on the prize, that I became victim to my own image, that my lifestyle became more important than my music, that I surrounded myself with the wrong people, that I betrayed his belief in me. And that if I had not made the selfish mistakes I did, then somehow I would have saved Paul. I know it’s a fantasy, but it haunts me to this day. I feel somehow responsible for what happened to him—even if that makes no sense to anyone but me.”

(Elliot Murphy peforming with Bruce Springsteen in 2007)

Leave a Reply

Only members can comment. Become a member. Already a member? Log in.